by Anna Belfrage

It is easy to sit on the lofty pinnacle of hindsight and condemn people who have lived long since for being bigoted. I guess there will come a time when the people of the future will sit on their equally lofty pinnacles and laugh softly at us and our stupid mistakes – assuming of course, that there will be a future world with people to build hindsight pinnacles.

This does not mean that our ancestors weren’t bigoted. Of course, they were. But their beliefs and prejudices were the consequences of the world they lived in, which is why it makes little sense to accuse a 16th century man of being a misogynist, or bemoan the lack of strong independent female role models in the 17th century. (Although, in actual fact, there were plenty of strong women in the 17th century – as in all preceding centuries. If not, the human race would have died out long ago…)

Today’s post is about a man I don’t like. And yet, I find him fascinating – plus I can’t help but admire just how adroitly the man shifts his allegiances, managing always to stay ahead in times as tumultuous as those of the 17th century. So, with no more ado, I give you Anthony Ashley Cooper – not always likeable, but always a man true to his own interests, which, of course, is a doubtful quality at best.

|

| Anthony Ashley Cooper |

Our hero entered the world in the summer of 1621, into a comfortable life of well-to-do gentry. His father was a Sir John Cooper, but before the age of nine, our Tony was an orphan, left in the tender care of guardians. These guardians would ensure Anthony got a good, Christian education, mostly at the hands of Puritan tutors – something which would affect Anthony’s outlook on life significantly in the future.

A bright and ambitious boy, Tony matriculated at Exeter College in Oxford at the tender age of 15, but was kicked out within the year due to having “fomented a riot”. Tony was destined to go through life fomenting riots of one type or the other, so this early start should not come as a surprise – the fledgling man was merely flexing his wings.

So, no degree at Oxford, and instead Anthony was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn, there to study – unsurprisingly – the law. He was probably happy to be able to combine his studies of the temporal with further advancement of the spiritual, and was yet again exposed to Puritan beliefs, this time at the hand of two zealous chaplains.

One could see where this was leading: an intelligent, independently wealthy young man, influenced by the beliefs of the Puritans – wow, we had a Commonwealth man in the making! Except that we didn’t. At 19, young Tony married Margaret Coventry, who came with the obvious advantage of being the daughter of Thomas Coventry, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. No matter his religious preferences, young Tony had thereby entered the royal circle – a good place to be, for a man who had every intention of leaving his mark on the world.

While still a minor, Anthony was elected an MP for Tewkesbury in the Short Parliament. As the name indicates, this was a short parliament – very short, even – and when elections were called for the Long Parliament, Tony was asked not to stand. He did anyway, won the seat, but was blocked from taking it because it was suspected Antony would prove too sympathetic to the king.

|

| Charles I - by divine right |

By now, England was already sliding down that very muddy slope leading to Civil War. Charles I had his own ideas as to how to rule, most of them based on the fact that he was king by divine right and therefore had little reason to listen to Parliament. This was not an opinion appreciated by the MPs – or a majority of the landed gentry. But from a genuine desire to rein in the king to actually challenging him on the battlefield, the step was huge. And yet, in 1642, England exploded into war, with our Tony firmly in the royalist camp – despite a strong belief in Parliament as an institution. I guess at the time he believed the king would prevail…

|

| Handsome Maurice |

In 1643 he raised his own troop, fought bravely at various battles – and ended up in a major quarrel with Prince Maurice, yet another of the king’s Palatinate nephews, but (deservedly) of much less fame than handsome dashing Prince Rupert. Anthony was miffed, to say the least, and maybe this was why he defected to the Parliamentarian side in 1644. Or maybe Anthony, ever the opportunist, realised how things would end. Whatever the case, our Tony shifted allegiances for the first – but not the last – time in his life.

The Parliamentarians viewed their new recruit with some suspicion – until Anthony explained he just couldn’t stand it, how the Catholics were influencing the king. Well, every good Puritan knew just how evil the papists were, and for a man to attempt to flee their control was totally understandable. This is a first instance of what would become a tiresome chorus in Anthony’s future political life – a deep-seated fear of all those who clung to the Catholic faith.

The war ended. Anthony was probably among those who opposed the regicide of Charles I, but was savvy enough to keep his head down, which resulted in him working closely with the interregnum government. He also found time to replace his dead first wife with a new, nubile little thing named Frances Cecil, with whom he was to experience three years or so of contentment before she died in 1652, leaving him a widower with two toddlers of which only one would survive into adulthood.

Our Anthony had other matters with which to concern himself than the raising of his children. He was an up-and-coming man, forgiven the sin of once having been a royalist, and a member of the Council of State. He had the ear of Oliver Cromwell – even voted for having Cromwell acclaimed as king in 1654 – but remained a firm believer in Parliament as the cornerstone in governing England. When Cromwell showed tendencies to want to rule without Parliament – after all, Cromwell had a huge Army at his disposal – Anthony broke with Cromwell. The man, it seemed, had some backbone, as he would show over the coming years when he opposed several of Cromwell’s proposals.

Tony spent some years out in the cold. The impoverished and exiled Charles Stuart contacted him, promising all sorts of things if Anthony were to re-join the royal camp, but in 1655 only a fool would bet on Charles against Oliver – Cromwell was too powerful and capable to be overthrown by a royalist rabble.

However, Cromwell died sooner than expected. His son was a pathetic failure, and all over the country closet royalists sniffed the air and hoped for change. Ever sensitive to changing moods, Anthony therefore decided to throw his lot in with Charles Stuart – rather late in the day, one would think, seeing as this was 1660, but the new king was grateful and Anthony was created Baron Ashley – after being pardoned for his support of the English Commonwealth.

From Anthony’s perspective, the new king ascended his throne under a huge burden of gratitude towards the Parliament who had invited him to return. Expectations were therefore that Charles II would do little without consulting this august body – but Charles’ advisors had other ideas (as did Charles himself: he may have deplored some of his father’s actions, but wasn’t about to roll over and play dead at the say-so of Parliament)

|

| Charles II - restored |

Once the king was happily crowned, Anthony returned to politics with fervour – and a tendency to bite the hand that fed him. He opposed the king’s marriage to Catherine of Braganza, he opposed any policy that moved England in the direction of popish France, and out of principle he opposed anything Charles’ Lord Chancellor, the Earl of Clarendon, might propose.

He was a vociferous opponent of the Clarendon Code – the act of legislation whereby it would be forbidden to adhere to any church other than the Church of England. He even went as far as recommending that not only Protestant non-conformists, but also loyal Catholics (assuming they kept well to the background) should be excluded from penalties. The king agreed; Parliament did not.

In general, for the first few years, Charles found Anthony an able servant. But by 1666 they had their first serious falling out over Irish politics, and in 1667 they clashed again – this time over Clarendon. At the time, Clarendon was out of favour – he had failed miserably in convincing Parliament to deliver to Caesar what Caesar wanted, whether it be money or laws. Charles was angered – and sick and tired of Clarendon’s tendency to treat him as if he were a mindless boy – so he didn’t exactly protest when some of his nobles banded together in an effort to impeach Clarendon.

One would have thought Anthony would have joined the band-wagon, but instead he seemed to take a perverse pleasure in supporting the under-dog – and aggravating the king, especially in view of the fact that Anthony and Clarendon had been at loggerheads for years. Whatever the case, there was no impeachment. Instead, Clarendon was run out of the country.

In Clarendon’s place, the King now relied on the Cabal Ministry, so called because it consisted of the Lords Buckingham, Ashley, Arlington, Lauderdale and Clifford. Not that the Cabal ever really worked together – initially Anthony was in the dog-house for supporting Clarendon, while Buckingham and Arlington were busy tearing at each other.

The Cabal quickly acquired a reputation for lewdness and debauchery. Buckingham, as an example, duelled openly with the husband of his mistress (!), and, even worse, insisted his illegitimate son with said mistress be baptised in Westminster Abbey. Lauderdale was a larger than life character whose behaviour rarely conformed to what was expected of a statesman. Anthony, on the other hand, was a man who rarely gave way to private indulgences, his focus always on the one thing he truly coveted: power.

|

| Anthony Ashley Cooper |

In 1672, Anthony was created Earl of Shaftesbury and Lord Chancellor of England. He had reached his pinnacle, and an element of gratitude on his side would not have come amiss. Our Tony did not reason quite like that – he was the most capable man around, and the king was damned lucky to have him. Besides, Anthony wanted more: he wanted an England happily rid of Catholics in position of power and was irritated by the king’s less than enthusiastic reaction to this oh, so important undertaking.

The king, unfortunately in Anthony’s opinion, was married to a Catholic – a barren Catholic to boot. Even worse, Anthony was beginning to suspect that the Duke of York, Charles’ brother and heir apparent, was a closet papist. Not good, as per Anthony.

He wasn’t alone in voicing that opinion. While others proposed the king legitimise his eldest bastard son, the Duke of Monmouth, Anthony instead suggested the king divorce his useless wife and marry a fertile Protestant princess. The king’s saturnine face set in a mask of displeasure at these suggestions. Charles loved his son, but he had no intention of legitimising him, as he saw this as potentially weakening the royal position – plus he had serious doubts as to his son’s ability to rule. And as to his wife, Charles was more than aware of how hurt she was by his constant infidelities. He wasn’t about to add the humiliation of divorce to her heartaches.

Anthony retaliated by supporting the 1673 Test Act, legislation aimed at barring Catholics from holding civil or military offices in England. In brief, the Test Act required that all holders of such office take communion as per Anglian rites at least once a year.

The Duke of York did not take communion. Instead, in September of 1673, the Duke married Catholic Mary of Modena, a pretty fifteen-year-old branded “the Pope’s daughter” by the English. Suddenly, there was a real possibility that the by now openly Catholic Duke might sire a son – a Catholic son who would, in all possibility, inherit the English throne. A catastrophe in the making, in Anthony’s opinion, and for the rest of his life he dedicated a significant part of his talents and energies to attempting to stop the Duke of York from ever becoming king. Obviously, this didn’t exactly endear him to the king.

|

| Useless Catherine... |

Nor was the king all that pleased by Anthony’s insistence that he divorce his Catholic wife and remarry, which is why in 1673 he removed Anthony from the post of Lord Chancellor. He may have pulled Anthony’s claws, but not his teeth, and in 1674 an incensed Anthony gave a speech in the House of Lords, warning his peers that the 16 000 Catholics living in London were on the verge of rebellion. Not true, but the speech was well received in these anti-papist times, and the poor Catholics were forcibly expelled from London.

Anthony went further, suggesting to Parliament that any king or prince of the blood who married a Catholic was effectively committing high treason. The king was livid. The Duke of York was apoplectic. Anthony sat back and smirked, fanning the flames of bigotry in Parliament until there was serious intent of accusing the Duke of York of treason. The king prorogued Parliament to protect his brother. Charles also sacked Shaftesbury (Anthony) from all royal offices – the rift between the two was never to be healed.

In 1678, things came to a head. This was the year when that despicable creature

Titus Oates rose to prominence by disclosing the Popish Plot. Not that there was any plot – Titus had made it all up – but the resulting furore created just the platform our boy Tony needed. “

I will not say who started the Game, but I am sure I had the full hunting of it,” he said. He most certainly did, using Oates’ twisted inventions to purge Parliament of papists and to launch his final effort to permanently bar the Duke of York from the succession, the Exclusion Bill.

Once again, Anthony suggested the king divorce his wife and marry someone younger and fertile. Once again, Monmouth was put forward as a far more palatable heir than the Duke – merely because he was Protestant. Not that Anthony held Monmouth in high regard – he considered the young man vain and spoiled, and initially scoffed at the notion of having a bastard ascend the throne. At the same time, there was something very tempting about the idea of having a king permanently beholden to Parliament for his title – after all, should he not perform, all one had to do was to bring up the bastardy issue.

Anthony underestimated the king. In fact, most of his contemporaries committed the same mistake, failing to recognise that on some issues, this flexible king would not be moved, and these issues included the succession, his refusal to legitimise Monmouth, and his approach to his marriage – divorce was not an option.

Anthony also underestimated his companions. Not all of them wanted to be tethered to a man described by Dryden as “

Restless, unfixed in principles and place”. Below Anthony’s feet, the ground began to shift, old loyalties dissolving, new ones forming. The excesses fuelled by the Popish Plot, resulting in the death of innocent men such as Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Ireland, were laid (justly) at Anthony’s feet.

In 1681, Anthony ended up kicking his heels in the Tower – accused of treason. The charges, however, could not be made to stick, and in 1682 he was released, but the mood of the country had changed, the Whig party to which Anthony belonged (he’d more or less founded it) challenged by the emerging Tories.

Feeling isolated and threatened – and still convinced it would be a disaster to the country to have a Catholic king – Anthony urged Monmouth and fellow conspirators to raise the flag of rebellion. The others weren’t all that keen, so instead Anthony began to toy with the idea of assassinating the king – and the Duke of York. Our hitherto intelligent – if bigoted – hero was losing it, finding little support for this radical idea. (A year or so later, in 1683, others would attempt to murder the Stuart brothers in the so called Rye House Plot, but by then Anthony was dead and no longer in a position to care about the English succession.)

By November of 1682, things were becoming sticky for our Tony, which is why he fled the country, seeking refuge in Amsterdam, where he died alone in January of 1683 after an extended illness. I don’t think all that many mourned his loss – least of all the Duke of York.

|

| Anthony Ashley Cooper |

Anthony Ashley Cooper was a crass and unsentimental character, quick to jump ship when his personal interests so required, incapable of rising above his religious prejudices. But in some things he was fanciful, such as in his belief that the souls of dead men rose through the skies to animate a distant star, forever tied to heaven’s firmament. If so, his star must be singularly dark, as red as the blood of the poor Catholics he spent a lifetime persecuting. But then, as I said in the beginning, it is easy to claim the moral high-ground from the perspective of three centuries and more. Who knows what any of us would have said or done, had we been born in a time so defined by religious tension and political instability as the 17th century?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

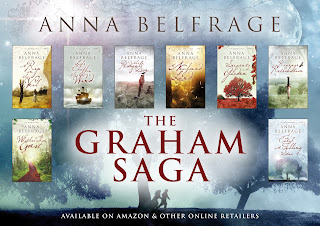

Anna Belfrage is the successful author of seven published books, all of them part of

The Graham Saga. Set in 17th century Scotland, Virginia and Maryland, this is the story of Matthew Graham and his wife, Alex Lind - two people who should never have met, not when she was born three centuries after him.

Anna's books have won several awards and are available on

Amazon, or wherever else good books are sold.

For more information about Anna and her books, please visit her

website. If not on her website, Anna can mostly be found on her

blog.