|

| Martha Ray by Nathaniel Dance, 1777 |

It’s a story that could be taken from 21st century news media. The evening of April 7, 1779, Miss Martha Reay left the theatre with a friend. As she started to get into her coach, James Hackman shot her in the face with a pistol, and then tried to kill himself with a second pistol. Within a year or so of her death, the victim was considered somehow at fault in her own murder, even though he did not deny killing her. This case was a sensation in the press of the day.

Who was Martha Reay? Strictly speaking, in terms of the society in which she was born, Martha Reay (or Ray, or Raye, or other variations depending on the source) was no one. She was born sometime between 1742-1746 in Elstree in Hertfordshire, the daughter of a corsetmaker and his wife(?), a servant. She was apprenticed to a milliner or dressmaker at the age of 13 or so by her father. When Martha reached the age of 16, her father allegedly took her to a procuress with a prospect of prostituting her. By all accounts, she was an attractive girl (not strictly a beauty, but fresh and pretty in appearance) with a good singing voice and a kind nature. Whether through the efforts of the procuress or by other means, Martha became the mistress of John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, when she was somewhere between the ages of 17 and 19.

|

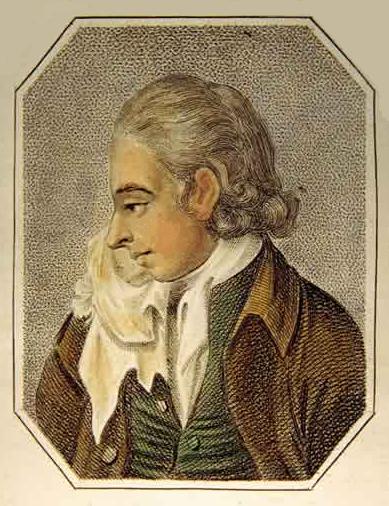

| John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, engraving, 1774 |

The Earl was a married man, aged about 44 years, and a career politician with a serious love of music. He had naval interests and was a patron of Captain James Cook, who named the Sandwich Islands for the Earl. (Contrary to the myth, the “sandwich” of bread and meat named for him was his quick meal to allow him more time at his desk, not the gaming table.) Unhappily married with only one living child (a son and heir also named John), he separated from his wife in 1755, shortly after which she was found to be insane by the Court of Chancery and was made a ward of the court. While his wife remained in permanent seclusion, he was unable to divorce and remarry.

When Lord Sandwich took Martha under his “protection”, he first placed her in a little house in Covent Garden with a companion, where he provided her with music masters. Whether the sexual relationship started immediately or later, the Earl took her (and her companion) to his family home Hinchingbrooke and treated her for all intents and purposes as his wife. She served as hostess at dinners Lord Sandwich hosted at the Admiralty Club for fellow politicians, and sang in two seasons of oratorios sponsored by the Earl. Over a 10-year period, Martha bore him 5 living children (4 sons and a daughter), whom he acknowledged. Sources indicate she actually had 9 children by the Earl, but only 5 survived. All accounts indicate that they were an affectionate couple.

|

| John Hackman, hand-coloured copper engraving, 1810 |

In 1774, John Hackman (a birth date of 1752 put his age at 22 at this time ) met the Earl while riding with a neighbour of the Earl’s, and was invited to dinner. At this point, he met Martha. Born in Hampshire, he was a handsome young man with the rank of ensign in the 68th regiment of the foot, of a respectable lower middle class family (originally destined for a trade, he went into the military instead.) Apparently, he conceived a romantic desire to rescue Martha from the Earl’s clutches. Martha was several years older than Hackman and there is no indication she had feelings for him. Being in the neighbourhood, they met multiple times. Hackman asked her to marry him and she turned him down. Accounts indicate Martha cited her loyalty to Lord Sandwich and that she had no desire to marry a military man. Shortly afterwards, Hackman was posted to Ireland. In 1776 he was promoted to lieutenant, but subsequently had resigned from the army to become a clergyman, supposedly in hope that Martha would change her mind and marry him. In February of 1779, he was ordained as a deacon, then a priest, and was assigned as rector of Wiveton in Norfolk.

Apparently, Hackman’s infatuation with Martha continued, possibly even grew, throughout this separation, and career change. (There is no indication he actually served in his clerical capacity.) He went to London, and sent Martha a note asking her to meet him. Accounts indicate she refused and told him to give it up, in essence. (This response appears to be the only letter known to have been written by Martha in the case.) Accounts indicate that his acquaintances noted that he was increasingly depressed. Shortly after this, on April 7, he followed Martha to the theatre, where he saw her in company including Lord Coleraine, who he decided was her current lover. He went to get 2 pistols, waited in a nearby coffee house, then, when he saw her leaving the theatre, committed the crime.

Stunned by her murder, Lord Sandwich had Martha buried next to her mother in Elstree. (Some accounts indicate he had her name engraved on a silver plaque which was mounted on her coffin.) In the meantime, during his murder trial, John Hackman pleaded innocent, saying he had not intended to kill Martha but only himself and that shooting her was a sudden impulse or frenzy, and his attorney said that he was insane. Judge and jury did not agree, especially because he had 2 pistols with him, and found him guilty. (Several witnesses also testified, which did not help his cause.) He was hanged at Tyburn April 19, 1779. Accounts indicate he met his end with bravery, asking to be buried near Martha, which did not happen. (His body was dissected at Surgeon’s Hall in London.)

The newspapers reported the case heavily, initially objectively. The supposed love triangle made it irresistible. Subsequently, Hackman's handsome appearance, his despair over his failed courtship and the death of his love resulting from his crime of passion made him a more sympathetic character. Speculation that Martha had somehow led him on then spurned him began circulating. Subsequently, a pamphlet (author anonymous) was published by G. Kearsley in Fleet Street, portraying John Hackman as good hearted yet misguided young man overwhelmed by his desire to save an undeserving woman. The romance combined with the facts that Hackman was a clergyman while Martha was a fallen woman appealed to the public’s imagination.

In March of 1780, G. Kearsley brought out a book titled LOVE AND MADNESS: A STORY TOO TRUE (written by Herbert Croft but published anonymously), to be the correspondence of John Hackman and Martha Reay over several years, supporting the view of Martha as the older woman taking advantage of a naive younger man then casting him aside, leading him to desperation. The book went into 9 editions. Even though the correspondence was forged and the book considered an epistolary novel when the author’s identity became known, many accepted it as factual. Public opinion leaned towards sympathy with the murderer, and a feeling that the victim had brought her death on herself.

Although Martha was known to have been concerned about financial security for herself and her children (given that the Earl was significantly older than she was and not overly wealthy), she had actually considered becoming a professional singer. There is no indication that she was ever unfaithful to the Earl or that she encouraged Hackman to believe she had feelings for him. Hackman’s known letters indicated that he chose to believe that she might marry him; this belief may have had roots in his obsession with an attractive woman whom he felt needed to be rescued or, even more simply, a refusal to accept that she did not want to be with him. In my opinion, evidence does not support the theory that Martha toyed with him then cast him aside.

After Martha’s death, Lord Sandwich took care of their children who continued to live with him. Although one son died, the other 3 had opportunities and their daughter married an admiral. Lord Sandwich died in April of 1792. Mary Hervey, Lady Fitzgerald, was shown as his last mistress by one source, but another referred to her as a good friend to the Earl. Most biographical references for the Earl that I found do not mention a mistress after Martha. It seems he remained faithful to Martha’s memory. I found nothing to indicate that he believed that Martha enticed Hackman. Sadly, you can still find speculation that Martha led James Hackman on in accounts today.

Sources include:

CASE and MEMOIRS of Miss MARTHA REAY, to which are added, REMARKS, by Way of Refutation on The CASE and MEMOIRS of the Rev. Mr. Hackman. London: M. Folingsby and C. Fourdrinier, 1779. (ECCO Print Edition)

Stebbins, Lucy Poate. LONDON LADIES True Tales of the Eighteenth Century. New York: Columbia University Press, 1952.

EverythingExplained.com. "John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich explained" (no author or post date shown). HERE

ExecutedToday.com "1779: James Hackman, sandwich wrecker" by Headsman, posted April 19, 2015. HERE

Plagiary. "LOVE AND MADNESS: A Forgery Too True" by Ellen Levy, 2006. HERE

Pen and Pension. "The Rev. James Hackman and the Murder of Martha Reay" posted June 10, 2015 by William Savage. HERE

Royal Favourites. "English Earls' and Countesses' Lovers and Mistresses" posted by Eu Royales (no date provided). HERE

Smithsonian.com. "Fatal Triangle" by John Brewer, Smithsonian Magazine, May 2005. HERE

Watford Observer. "Martha Ray" (no author or post date shown). HERE

Illustrations:

Martha Ray: Wikimedia Commons, HERE

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich: Wikimedia Commons, HERE

John Hackman: Wikimedia Commons, HERE

~~~~~~~~~~

Lauren Gilbert, author of HEYERWOOD: A Novel, holds a B.A. in English and is a long-time member of JASNA. She lives in Florida with her husband, and is working on her second book A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT. Please visit her website here for more information.

Apparently, Hackman’s infatuation with Martha continued, possibly even grew, throughout this separation, and career change. (There is no indication he actually served in his clerical capacity.) He went to London, and sent Martha a note asking her to meet him. Accounts indicate she refused and told him to give it up, in essence. (This response appears to be the only letter known to have been written by Martha in the case.) Accounts indicate that his acquaintances noted that he was increasingly depressed. Shortly after this, on April 7, he followed Martha to the theatre, where he saw her in company including Lord Coleraine, who he decided was her current lover. He went to get 2 pistols, waited in a nearby coffee house, then, when he saw her leaving the theatre, committed the crime.

Stunned by her murder, Lord Sandwich had Martha buried next to her mother in Elstree. (Some accounts indicate he had her name engraved on a silver plaque which was mounted on her coffin.) In the meantime, during his murder trial, John Hackman pleaded innocent, saying he had not intended to kill Martha but only himself and that shooting her was a sudden impulse or frenzy, and his attorney said that he was insane. Judge and jury did not agree, especially because he had 2 pistols with him, and found him guilty. (Several witnesses also testified, which did not help his cause.) He was hanged at Tyburn April 19, 1779. Accounts indicate he met his end with bravery, asking to be buried near Martha, which did not happen. (His body was dissected at Surgeon’s Hall in London.)

The newspapers reported the case heavily, initially objectively. The supposed love triangle made it irresistible. Subsequently, Hackman's handsome appearance, his despair over his failed courtship and the death of his love resulting from his crime of passion made him a more sympathetic character. Speculation that Martha had somehow led him on then spurned him began circulating. Subsequently, a pamphlet (author anonymous) was published by G. Kearsley in Fleet Street, portraying John Hackman as good hearted yet misguided young man overwhelmed by his desire to save an undeserving woman. The romance combined with the facts that Hackman was a clergyman while Martha was a fallen woman appealed to the public’s imagination.

In March of 1780, G. Kearsley brought out a book titled LOVE AND MADNESS: A STORY TOO TRUE (written by Herbert Croft but published anonymously), to be the correspondence of John Hackman and Martha Reay over several years, supporting the view of Martha as the older woman taking advantage of a naive younger man then casting him aside, leading him to desperation. The book went into 9 editions. Even though the correspondence was forged and the book considered an epistolary novel when the author’s identity became known, many accepted it as factual. Public opinion leaned towards sympathy with the murderer, and a feeling that the victim had brought her death on herself.

Although Martha was known to have been concerned about financial security for herself and her children (given that the Earl was significantly older than she was and not overly wealthy), she had actually considered becoming a professional singer. There is no indication that she was ever unfaithful to the Earl or that she encouraged Hackman to believe she had feelings for him. Hackman’s known letters indicated that he chose to believe that she might marry him; this belief may have had roots in his obsession with an attractive woman whom he felt needed to be rescued or, even more simply, a refusal to accept that she did not want to be with him. In my opinion, evidence does not support the theory that Martha toyed with him then cast him aside.

After Martha’s death, Lord Sandwich took care of their children who continued to live with him. Although one son died, the other 3 had opportunities and their daughter married an admiral. Lord Sandwich died in April of 1792. Mary Hervey, Lady Fitzgerald, was shown as his last mistress by one source, but another referred to her as a good friend to the Earl. Most biographical references for the Earl that I found do not mention a mistress after Martha. It seems he remained faithful to Martha’s memory. I found nothing to indicate that he believed that Martha enticed Hackman. Sadly, you can still find speculation that Martha led James Hackman on in accounts today.

Sources include:

CASE and MEMOIRS of Miss MARTHA REAY, to which are added, REMARKS, by Way of Refutation on The CASE and MEMOIRS of the Rev. Mr. Hackman. London: M. Folingsby and C. Fourdrinier, 1779. (ECCO Print Edition)

Stebbins, Lucy Poate. LONDON LADIES True Tales of the Eighteenth Century. New York: Columbia University Press, 1952.

EverythingExplained.com. "John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich explained" (no author or post date shown). HERE

ExecutedToday.com "1779: James Hackman, sandwich wrecker" by Headsman, posted April 19, 2015. HERE

Plagiary. "LOVE AND MADNESS: A Forgery Too True" by Ellen Levy, 2006. HERE

Pen and Pension. "The Rev. James Hackman and the Murder of Martha Reay" posted June 10, 2015 by William Savage. HERE

Royal Favourites. "English Earls' and Countesses' Lovers and Mistresses" posted by Eu Royales (no date provided). HERE

Smithsonian.com. "Fatal Triangle" by John Brewer, Smithsonian Magazine, May 2005. HERE

Watford Observer. "Martha Ray" (no author or post date shown). HERE

Illustrations:

Martha Ray: Wikimedia Commons, HERE

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich: Wikimedia Commons, HERE

John Hackman: Wikimedia Commons, HERE

~~~~~~~~~~

Lauren Gilbert, author of HEYERWOOD: A Novel, holds a B.A. in English and is a long-time member of JASNA. She lives in Florida with her husband, and is working on her second book A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT. Please visit her website here for more information.