by Arthur Russell

Celebrating Samhain

The Hill of Ward near Athboy in Co Meath is regarded as the site where the traditional celebration of Samhain was centred in pre-Christian Ireland. The ancient Celtic name for the Hill is Tlachtga (from the old Gaelic words meaning “Earth Spear”). This derives from the name of the Celtic goddess of Fertility. An associated legend about her tells that Tlachtga (pronounced Clackda) was a Witch and the daughter of the powerful wizard and chief Druid, Mug Ruith.

Note – Older legends of Mug Ruith suggest he was a Sun God.

The legend speaks of Tlachtga and Mug Ruith journeying to Italy to put themselves under the tuition of a powerful wizard called Simon Magnus. In course of this, the three constructed a flying wheel called the Roth Rámach, which they used to sail through the air to demonstrate their powers. Mug Ruith and Tlachtga returned to Ireland and brought the flying wheel with them. The legend also relates that the wizard’s three sons raped Tlachtga and fathered triplet sons on her. She died after giving birth and the earthworks that can still be seen on the summit of the Hill of Ward (Tlachtga) were raised over her grave and the annual Samhain festival inaugurated to her honor.

Samhain Rituals

The Celtic feast of Samhain (Samhain is the Gaelic word for November) marks the beginning of Winter. The tradition was to extinguish all fires across the countryside before sunset on the eve of the feast. After darkness fell, the druids who had gathered on top of the Hill called Tachtla lit the first fire. The fire from this was transported by chariot to both Tara and Loughcrew as well as to five other designated sites throughout the land to relight fires there. From these fires all other fires in the land would be relit. The night sky would be illuminated by the spreading Samhain fires as they worked their way through the countryside. After Christianity arrived, the old pagan festival of Samhain were transformed into a celebration of All Souls or All Hallows to honour their dead who had passed to a better world. The notion that it was possible to more easily communicate with the dead during the darkening days as winter approached seemed to persist. From this came the name Hallow'eve (the eve of All Souls day) or Hallowe'en. Many of the associated traditional practices and games were kept and developed over succeeding centuries to what we know today.

Note – Among the many Hallowe'en traditions that developed over the centuries in Celtic countries such as Ireland, Scotland, Wales and the Isle of Man was the making of Hallowe'en lanterns using the humble turnip grown on many farms. Selected turnips were chosen and had the central pulp removed; holes were cut in the shell of the bulb to represent eyes, nose and mouth and a lighted candle placed inside to be placed on gateposts and on windows on the night of Hallowe'en. Emigrants to the New World during the 18th and 19th century brought the lantern making tradition with them but adapted the much bigger and softer pumpkin as Hallowe'en ware. It is interesting to note that the tradition of using pumpkins (not turnips) as Hallowe'en lanterns has during the last century effectively come from the New World to replace the turnip as the favoured vegetable for the Hallowe'en lantern.

It is also interesting to note that the Pilgrim Fathers were not in favour of celebrating Hallowe'en at all, so it awaited the arrival of later waves of immigrants from Europe, especially Ireland and Scotland, to establish the celebration of Hallowe'en in the New World.

The Samhain Festival revived at Tlachtga’s Hill:

In recent years, the Samhain celebration has been revived at the Hill which is regarded as the centre for Samhain celebrations. It is expected that on the evening of each October 31st over 1000 people from many countries will gather in the Fairgreen of Athboy to observe the ancient ritual of Samhain on the ancient site. Tlachtga’s Hill is close to the town of Athboy in Co Meath, where on the evening of October 31st townspeople and anyone who cares to join them will assemble in the centre of the town, some wearing druid costumes and carrying lanterns, to walk the short distance to the hill outside the town. There they will light the traditional Samhain bonfire. In doing this, they will repeat and recall the actions of their ancestors of centuries before as they mark the passing of another year and the beginning of the coming winter.

As always, the emphasis will not be just to look back but also to look forward. The dead will duly remembered and honoured, as they should be.

The living, those who have lived through the year that is winding down to its annual sleep and who are alive to see this night, will be reminded by the fire that the dark winter days of November and December will pass. Light and life will return once more, all in due time, for everything under the Heavens has its season.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

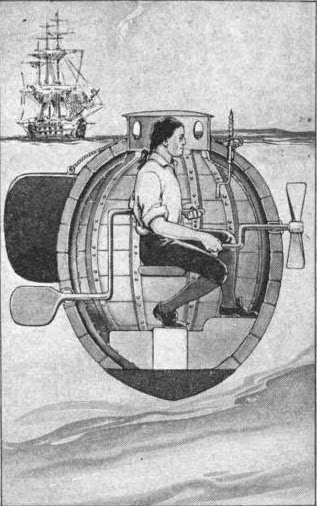

Arthur Russell is the Author of Morgallion, a novel set in medieval Ireland during the Invasion of Ireland in 1314 by the Scottish army led by Edward deBruce, the last crowned King of Ireland. It tells the story of Cormac MacLochlainn, a young man from the Gaelic crannóg community of Moynagh and how he and his family endured and survived that turbulent period of history. Morgallion has been recently awarded the IndieBRAG Medallion and is available in paperback and e-book form.

More information available on website - www.morgallion.com

|

| Aerial view of the earthworks on Tlachtga's Hill |

The Hill of Ward near Athboy in Co Meath is regarded as the site where the traditional celebration of Samhain was centred in pre-Christian Ireland. The ancient Celtic name for the Hill is Tlachtga (from the old Gaelic words meaning “Earth Spear”). This derives from the name of the Celtic goddess of Fertility. An associated legend about her tells that Tlachtga (pronounced Clackda) was a Witch and the daughter of the powerful wizard and chief Druid, Mug Ruith.

Note – Older legends of Mug Ruith suggest he was a Sun God.

The legend speaks of Tlachtga and Mug Ruith journeying to Italy to put themselves under the tuition of a powerful wizard called Simon Magnus. In course of this, the three constructed a flying wheel called the Roth Rámach, which they used to sail through the air to demonstrate their powers. Mug Ruith and Tlachtga returned to Ireland and brought the flying wheel with them. The legend also relates that the wizard’s three sons raped Tlachtga and fathered triplet sons on her. She died after giving birth and the earthworks that can still be seen on the summit of the Hill of Ward (Tlachtga) were raised over her grave and the annual Samhain festival inaugurated to her honor.

Whatever the Festival’s origin, the Hill of Ward, then known as Tlachtga, was established as a center of Celtic religious worship over 2,000 years ago focusing on the celebration of the feast of Samhain. From the beginning it was overshadowed by the more famous and prestigious neighboring site at the Royal seat on the Hill of Tara less than 10 kms to the east, but it remained for centuries the center of the annual Great Fire Festival of Samhain that signaled the onset of winter.

The rituals and ceremonies carried out here by the pre-Christian Irish offered assurance to the people that the powers of darkness, which had by that time of year become strongly established over the land would be overcome, and the powers of light and life would eventually prevail. Animal bones were cast into the fires of Samhain, which added a special spiritual significance to the ceremonial flames. The fire was called 'tine chnámh' (pronounced tina kin-awve) or bone fire, from which the English word ‘bonfire’ is derived. The Celts believed that Oiche Samhain (the Night of Samhain) marks a time of year when the veil between the world of the Living and the world of the Dead melts away for a short while. During those hours the souls of all who had died since the last Samhain moved into the next life and there was relatively free movement of the dead as they made return visits to their former lives. The Celtic Druids considered the Hill of Tlachtga to be a place where the veil between living and dead was at its thinnest on that night.

The pre-historic landscape of the Boyne Valley.

|

| Map of the Boyne Valley area showing pre-historic sites |

The ceremonial Hill is located midway between the Royal site on the Hill of Tara and the Neolithic burial sites of Loughcrew to the North-west; both of which have their own burial structures which are aligned to the seasonal position of the Sun as it goes through its annual cycle around the sky.

Note - The Mound of the Hostages on the crest of the Hill of Tara is actually aligned to the rising sun on November 1st. Tlaghtga is located at the edge of the Boyne Valley, an area which is already rich in pre-historic sites. These include – Tara, the ancient site for the Irish Árd Ríthe (High Kings), Brú na Bóinne encompassing Newgrange (associated with the Winter Solstice), and the structures of Knowth and Dowth, Tailteann – which is associated with Loughcrew – which has a complex of passage tombs aligned to the equinox sunrises in March and September.

|

| Mound of the Hostages at Tara |

Samhain Rituals

The Celtic feast of Samhain (Samhain is the Gaelic word for November) marks the beginning of Winter. The tradition was to extinguish all fires across the countryside before sunset on the eve of the feast. After darkness fell, the druids who had gathered on top of the Hill called Tachtla lit the first fire. The fire from this was transported by chariot to both Tara and Loughcrew as well as to five other designated sites throughout the land to relight fires there. From these fires all other fires in the land would be relit. The night sky would be illuminated by the spreading Samhain fires as they worked their way through the countryside. After Christianity arrived, the old pagan festival of Samhain were transformed into a celebration of All Souls or All Hallows to honour their dead who had passed to a better world. The notion that it was possible to more easily communicate with the dead during the darkening days as winter approached seemed to persist. From this came the name Hallow'eve (the eve of All Souls day) or Hallowe'en. Many of the associated traditional practices and games were kept and developed over succeeding centuries to what we know today.

Note – Among the many Hallowe'en traditions that developed over the centuries in Celtic countries such as Ireland, Scotland, Wales and the Isle of Man was the making of Hallowe'en lanterns using the humble turnip grown on many farms. Selected turnips were chosen and had the central pulp removed; holes were cut in the shell of the bulb to represent eyes, nose and mouth and a lighted candle placed inside to be placed on gateposts and on windows on the night of Hallowe'en. Emigrants to the New World during the 18th and 19th century brought the lantern making tradition with them but adapted the much bigger and softer pumpkin as Hallowe'en ware. It is interesting to note that the tradition of using pumpkins (not turnips) as Hallowe'en lanterns has during the last century effectively come from the New World to replace the turnip as the favoured vegetable for the Hallowe'en lantern.

It is also interesting to note that the Pilgrim Fathers were not in favour of celebrating Hallowe'en at all, so it awaited the arrival of later waves of immigrants from Europe, especially Ireland and Scotland, to establish the celebration of Hallowe'en in the New World.

The Samhain Festival revived at Tlachtga’s Hill:

In recent years, the Samhain celebration has been revived at the Hill which is regarded as the centre for Samhain celebrations. It is expected that on the evening of each October 31st over 1000 people from many countries will gather in the Fairgreen of Athboy to observe the ancient ritual of Samhain on the ancient site. Tlachtga’s Hill is close to the town of Athboy in Co Meath, where on the evening of October 31st townspeople and anyone who cares to join them will assemble in the centre of the town, some wearing druid costumes and carrying lanterns, to walk the short distance to the hill outside the town. There they will light the traditional Samhain bonfire. In doing this, they will repeat and recall the actions of their ancestors of centuries before as they mark the passing of another year and the beginning of the coming winter.

As always, the emphasis will not be just to look back but also to look forward. The dead will duly remembered and honoured, as they should be.

The living, those who have lived through the year that is winding down to its annual sleep and who are alive to see this night, will be reminded by the fire that the dark winter days of November and December will pass. Light and life will return once more, all in due time, for everything under the Heavens has its season.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Arthur Russell is the Author of Morgallion, a novel set in medieval Ireland during the Invasion of Ireland in 1314 by the Scottish army led by Edward deBruce, the last crowned King of Ireland. It tells the story of Cormac MacLochlainn, a young man from the Gaelic crannóg community of Moynagh and how he and his family endured and survived that turbulent period of history. Morgallion has been recently awarded the IndieBRAG Medallion and is available in paperback and e-book form.

More information available on website - www.morgallion.com