by Anna Belfrage

In July of 1689, the first battle of the Jacobite rebellion took place up in Scotland. I see some of you wrinkling your brows: for most people, the Jacobite rebellion is an 18th century thing involving Bonnie Prince Charlie and the brave Highlanders. Well, before there was a bonny prince there was an ousted king, grandfather to the young man who led the clans to their death at Culloden.

|

| James II |

In 1688, James II of England was faced with a most unpalatable challenge: seven of his Protestant grandees had offered the English crown to James’ son-in-law, William of Orange, and his daughter, Mary. Why? Well, the Protestant powers-that-were had been made most nervous back in June of 1688, when James II’s second wife, Mary of Modena, presented him with a healthy son.

One would assume the birth of a prince would have been greeted with joy. Problem was, James II and his wife were Catholics. The baby boy was therefore a vile papist, and England in the late 17th century was not exactly tolerant when it came to papists. The birth of little James Francis Edward was, according to the good Anglicans, a catastrophe. Prior to his birth, James’ heir was Mary, safely married to that most staunch of Protestants, Dutch William. With the baby prince, the English could potentially face a dynasty of Catholic kings, a fate to be avoided at all costs, even if the cost was treason.

No sooner was baby James Francis Edward born but the rumours started: the baby was obviously a changeling, smuggled in via a warming pan to replace the stillborn babe Mary of Modena had birthed. Anyone who has seen a warming pan and compared it size wise with a living baby would realise transporting a newborn child in one was risking the baby’s life, but people were more than happy to believe this lurid tale. Poor James. Poor Mary of Modena. This was a couple who’d seen more than their fair share of babies die away from them and now, when at last there was a healthy son, they had to listen to all this evil gossip. Even worse, it seemed it was James’ two eldest daughters who had fanned these rumours into life.

In November of 1688, William landed in England. Upon his arrival, there was a general stampede among James’ closest men, all of them falling over their feet in their eagerness to declare themselves for William.

Not all Protestants sided against James. Very many remained loyal to their king. James was a proven general and as his army was superior to that of William, one would have thought he’d chase his son-in-law straight back into the North Sea.

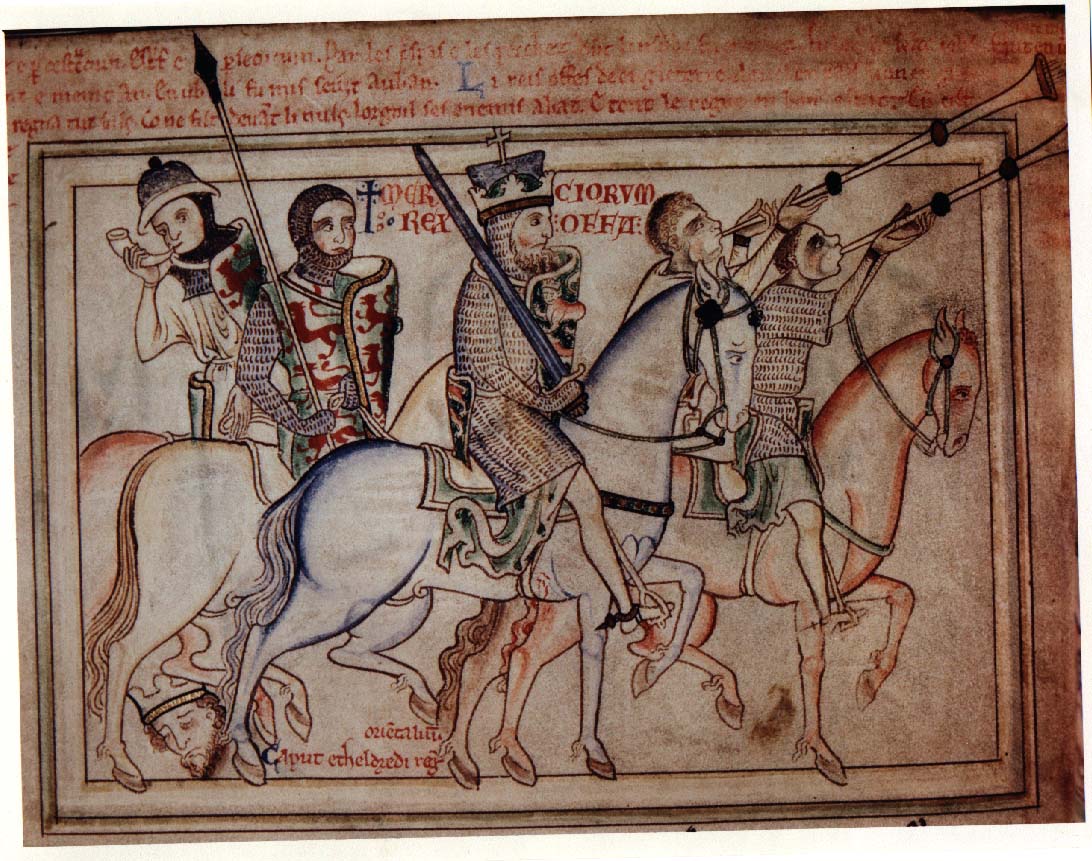

|

| Mary of Modena and James Francis Edward |

Problem was, James lost his nerve. First, he had no desire to submerge England into yet another civil war—he remembered well the terrors of the previous war. Secondly, too many of the men he had trusted and believed in had turned their backs on him. So James dithered. Never a good thing to do. William did not dither. Come December, James was a prisoner of his son-in-law, but William found all this rather uncomfortable so he obligingly looked the other way when James “escaped” and fled to France, where his wife and baby son were waiting.

Back in England, those loyal to James regrouped. Among these was a certain James Graham of Claverhouse, a Scotsman who had served both Charles II and James. In Ayrshire, John Graham went by “Bluidy Clavers”, held responsible for the brutal oppression of the Covenanter movement. This is probably not entirely correct: James Graham was married to Jean Cochrane, daughter to a very Presbyterian family, and in his letters he generally advocated leniency, not violence.

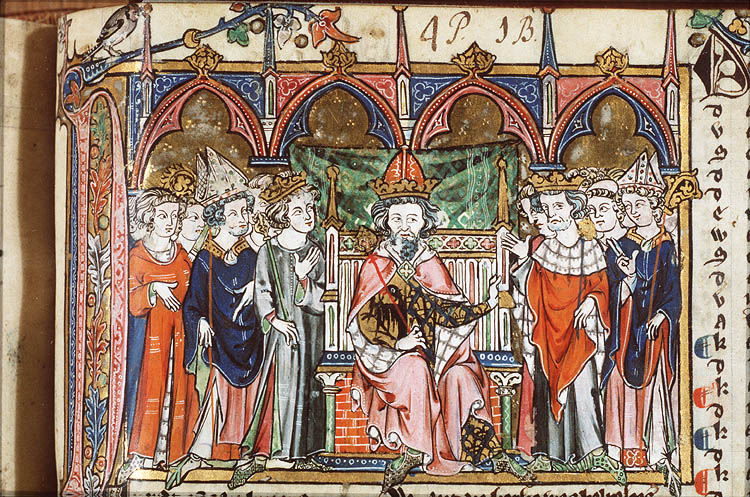

|

| James Graham |

Whatever the case, James Graham was a competent man. Among the last things James II did before fleeing England was to raise John Graham to the viscountcy by making him Viscount Dundee. In many ways an empty gesture, but James II also made Dundee commander-in-chief of the Scottish forces. This was not quite as empty a gesture—Dundee had quite the reputation as a soldier and inspired loyalty among the men who served with him.

In the beginning of 1689, Dundee did his best to convince his fellow Scotsmen that they should fight for their Stuart king. At one point, he even climbed up the extremely steep castle rock to ensure the Duke of Gordon, governor of Edinburgh Castle, remembered to whom he owed his loyalty. Gordon did, and for some months more he held the castle for the king—albeit with waning enthusiasm. To be fair to Gordon, his situation was precarious: James was nowhere close (he was in Ireland at the time) and William’s forces under Hugh Mackay were advancing north. Public opinion in Lowland Scotland was firmly with William, no matter how “Scottish” the Stuart dynasty may have been. Most Lowland Scots were suspicious of papists in general, and William of Orange had proved himself a capable defender of the Protestant faith.

|

| William III |

In April of 1689, the Scottish Estates decided to acclaim William as their king. Some days later, Dundee raised the Scottish Royal Standard, calling for all men loyal to their true king to join him. Many men did. Not quite as many as Dundee had hoped for, however, and his situation was made precarious when the Scottish Estates declared him a traitor and attempted to arrest him. Dundee entrusted his pregnant wife into the care of his father-in-law and took to the hills.

Over the coming months, Dundee breathed fire into the Highland hearts. Clan Cameron under Ewen Cameron of Lochiel brought a further 1800 men to the Jacobite cause, but leading an army of Highlanders was a challenge—as was keeping them fed. It is testament to Dundee’s leadership skills that he managed to keep his troops together throughout late spring and the summer of 1689. Meanwhile, Mackay marched in pursuit, his ranks swelled by eager volunteers. For a while there, Mackay and Dundee played a complicated game of hide-and-seek, neither of them willing to commit to a full out confrontation.

Things were to come to a head at Killiecrankie, a pass south-east of Blair Atholl. Blair Castle was under Jacobite control, thereby barring access to the Highland north and Mackay led his troops north to offer support to John Murray, at present besieging the castle. (This is all very complicated: Blair Castle was the seat of the Duke of Atholl and in an attempt to keep his options open no matter who won the ongoing conflict, Atholl himself retired to England, bemoaning the Jacobite garrison holding his castle while leaving his son, Murray, to “besiege” the castle. Thing is, the garrison was commanded by one Patrick Stewart, one of Atholl’s loyal retainers. A rather elegant way of hedging one’s bets…)

|

James Graham - not quite as dashing

as in the first pic |

When Dundee heard Mackay was trundling north and making for the pass at Killicrankie, he mobilised with speed. Here was a golden opportunity to wreak havoc on Dutch William’s men, and Dundee intended to make the most of it. Killicrankie was a two-mile pass, on one side bordered by the river Gerry, on the other by steep hills. Mackay must have been aware of the risk he took, but his information was probably not entirely up to date so it must have come as quite a surprise when Mackay’s army emerged from the pass only to find the slopes facing them bristling with Jacobite soldiers.

Retreating down the narrow track was the equivalent of suicide and so Mackay did the only thing he could do: he prepared for battle. He deployed his men, had his artillery move forward and then he waited for the Highlanders to charge. After all, everyone knew that once the Highlanders charged, discipline went out their head and Mackay was probably gambling on them becoming so disorderly he’d be able to fight back.

Mackay waited. And waited. He waited some more. His men were beginning to fidget. It was a nerve-wracking experience to stand in front of the slope, knowing full well the Highlanders had all the advantages on their side. Mackay’s men had the Gerry at their back, they couldn’t run left or right and before them the Highlanders had their muskets and swords at the ready.

The July afternoon waned. Men were thirsty and hungry and probably in need of a human break or two. Still, the Highlanders did not move. Guns roared, but Mackay’s cannon were too far away to cause any damage, nor did the shots provoke the Highlanders into doing something. Dusk began to seep upwards from the ground. The sun dipped out of sight. At last, Dundee ordered his men to attack. Wave after wave of Highlanders came rushing down the slope.

Mackay’s men did not stand a chance. Many of them were untrained, few had seen real action and here they were, staring at a horde of roaring men wielding swords. Many turned and fled. Most of these drowned in the Gerry. Some tried to jump across, but the river was too wide, and man after man fell to die in the waters. Others were hewn down, incapable of withstanding the sheer momentum of the Highlanders who came leaping down the hill.

There was blood, there was gore, there were screams. Men died, men fell. Bodies were trampled underfoot as the Highlanders rushed onwards. Approximately 2000 of Mackay’s 3500 men died. The Jacobite army had won the day and one would have thought the coming night would have been spent in rejoicing.

But it wasn’t only Mackay’s men that died. The Jacobites had losses of their own. In the final minutes of the battle, Dundee was hit by a musket ball just below his breastplate. By the time the battle dust had settled, Dundee was dead. He had won the battle but lost his life. Even worse, the Jacobite army had lost its general. The victory at Killiecrankie was therefore flavoured with the bitter taste of crushed hope. Without the gallant and talented Dundee, the Stuart cause in Scotland was a dead duck in the water.

|

| Mackay's men defending Dunkeld |

Mackay and 500 or so of his men managed to escape when the victorious Highlanders turned to looting Mackay’s baggage train. Desperate and exhausted, they made it to Stirling Castle, there to regroup. Some months later, Mackay led his troops to a decisive victory over the Jacobites at Dunkeld. The First Jacobite Rising had come to an end, but over the coming six decades or so the men of the Scottish Highlands would die repeatedly on behalf of the Stuarts—right up to the crushing defeat at Culloden.

Dundee was buried in St Bride’s crypt, Blair Castle. Some months later, his wife gave birth to a son—Dundee’s only known child. By then, Dundee was already becoming a legend, a valiant man who would rather die than betray his king. Not much of a comfort to his widow, I imagine.

Many, many years ago, a man chose to hold to the oath he had sworn to always serve and protect his king. To this day, the memory of James Graham lives on. In the words of Sir Walter Scott:

"Away to the hills, to the caves, to the rocks

Ere I own an usurper, I'll couch with the fox;

And tremble, false Whigs, in the midst of your glee,

You have not seen the last of my bonnet and me!"

Come fill up my cup, come fill up my can,

Come saddle the horses, and call up the men,

Come open your gates, and let me gae free,

For it's up with the bonnets of Bonny Dundee!

He waved his proud hand, the trumpets were blown,

The kettle-drums clashed and the horsemen rode on,

Till on Ravelston's cliffs and on Clermiston's lee

Died away the wild war-notes of Bonny Dundee.

Come fill up my cup, etc.

And just so you know, James Graham rides, fights and dies in the eight book of The Graham Saga. Such a gallant man deserves some air-time...

All pictures in public domain and/or licensed under Wikimedia Creative Commons

~~~~~~~~~~~

Had

Anna Belfrage been allowed to choose, she’d have become a professional time-traveller. As such a profession does not exist, she became a financial professional with two absorbing interests, namely history and writing.

Anna's most recent series is The King’s Greatest Enemy, a series set in the 1320s featuring Adam de Guirande, his wife Kit, and their adventures and misfortunes in connection with Roger Mortimer’s rise to power. The fourth instalment, The Cold Light of Dawn, was published in February 2018.

When Anna is not stuck in the 14th century, she's probably visiting in the 17th century, specifically with Alex(andra) and Matthew Graham, the protagonists of the acclaimed The Graham Saga. This is the story of two people who should never have met – not when she was born three centuries after him. The ninth book, There is Always a Tomorrow, was published in November 2017.

Anna has recently published the first book in a new series, The Wanderer. A Torch in his Heart tells the time-spanning story of Jason, Sam and Helle who first 3 000 years ago and have since then tumbled through time, trapped in a vicious circle of love, hatred and revenge.