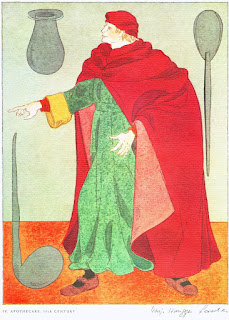

Medieval apothecaries were the equivalent of our modern pharmacists. An apothecary’s shop was full of various cures, most of which he prepared himself. He was usually a trusted member of the community, but at times, apothecaries were accused of practising magic or witchcraft. In an age before folk had easy access to doctors and when hospitals were religious foundations, more interested in curing your soul than your body, the apothecary was an ordinary person’s best hope of a cure or relief from an illness. Because apothecaries saw different people with various illnesses each day, most had a huge knowledge of the human body and herbal remedies.

Early in the Middle Ages, an apothecary would have cultivated all the plants and herbs needed for his medicines himself. Later, supplies became more organised, especially in cities like London, York and Bristol, with individuals growing plants to order for the apothecaries.

The recipes for the wines, syrups, cordials and medicines were passed down through the generations, from master to apprentice. They were closely guarded secrets too, since the most successful apothecary would have the most customers. While some apothecaries worked on a casual basis from their own homes, many had their own retail premises, usually a small shop. The front of the shop would have shelves full of medicines and herbs and in the back section, the apothecary would prepare medicines as and when they were needed. Ideally, he would also have access to a garden, where he could grow some of the less exotic herbs and plants he needed to prepare his cures. Some of the most popular medicines were prepared in advance, ready for sale, just as in a modern-day pharmacy. Other cures were prepared as and when needed, and were made up precisely, with the apothecary using his knowledge of the patient and the illness to prepare what he thought would be the ideal remedy.

Apothecaries were often spicers or pepperers as well. Because their work involved weighing out small amounts of herbs and spices for use in medicine, or for direct sale to customers, their trade was regulated by the Grocers’ Guild. It was impossible to separate the two businesses completely as both were involved in importing and distributing spices from abroad, for use in cooking and in the preparation of products such as spiced wines. In addition to food and drugs, apothecaries also sold inks and pigments to the stationers, beauty products and perfumes, substances used in fumigation and pest control and even good luck charms and novelties such as serpent-stones – what we know to be ammonite fossils.

A collection of medical recipes from the fifteenth century [now MS136 at the Literary Society of London] has remedies which make use of herbs that really could have performed the cure as intended:

For the Migraine take half a dishful of barley, one handful each of betony, vervain and other herbs that are good for the head; and when they be well boiled together, take them up and wrap them in a cloth and lay them to the sick head and it shall be whole – I proved.

A sick headache might well be eased by this poultice. Betony was a favourite herb in medieval times and was taken internally for a range of ailments. It’s still used today in treatments for nervous headaches and some types of migraine. Vervain is also used in modern medicine as a nerve tonic and as a calming restorative for patients in a debilitated condition. It too is used to treat migraine and depression.

For those troubled with digestive problems, this fifteenth century remedy would have helped:

To void Wind that is the cause of Colic take cumin and anise, of each equally much, and lay it in white wine to steep, and cover it over with wine and let it stand still so three days and three nights. And then let it be taken out and laid upon an ash board for to dry nine days and be turned about. And at the nine days’ end, take and put it in an earthen pot and dry over the fire and then make powder thereof. And then eat it in pottage or drink it and it shall void the wind that is the cause of colic.

Both these spices, anise and cumin, are carminatives, so this medicine would do exactly what it said on the tin – or earthen pot. The herbs dill and fennel could be used instead to the same effect – twentieth century gripe water for colicky babies contained dill. Wind and constipation were common preoccupations in the Middle Ages because folk ate so many pulses and little roughage, apart from cabbage.

Despite such suitable treatments as these, other remedies, despite the use of some exotic ingredients, could only have worked as panaceas. These concoctions are for gout:

Take badger’s grease and swine’s grease and hare’s grease and cat’s grease, dog’s grease and capon’s grease and suet of a deer and sheep’s tallow, of each equally much and melt them in a pan. Then take the juice of herb-robert, morell, mallow and comfrey and daisy and rue, plantain and maidenhair, knapweed and dragance, of each equally much juice, and fry them in the pan with the aforesaid greases, and keep it well, for the best ointment for gout is this. Or:

Take an owl and pluck it clean, and open it clean and salt it. Put it in a new pot and cover it with a stone and put it in an oven and let it stand till it be burnt. And then stamp [pound] it with boar’s grease and anoint the gout therewith.

A cough cure was more pleasant, consisting of the juice of horehound to be mixed with diapenidion and eaten. Horehound is good for treating coughs and diapenidion is a confection made of barley water, sugar and whites of eggs, drawn out into threads, so perhaps a cross between candy floss and sugar strands. It would have tasted nice and sugar is good for the chest, still available in an over-the-counter cough mixture as linctus simplex. Another pleasant cough treatment was coltsfoot comfits, like tiny sugary sticks of pale brown rock. King Henry III had the apothecary, Philip of Gloucester, supply him with 7½ lbs of diapenidion when the king visited the West Country in May 1265, along with 5lbs of grana, all together costing 7s 6d. My source for this [The Royal Apothecaries by Leslie G Matthews, 1967, pub by the Wellcome Historical Medical Library] suggests ‘grana’ meant aromatic seeds to aid digestion, like caraway or cumin, or it could have been Grains of Paradise, a kind of pepper. But ‘grana’ was also a name given to the exotic ‘kermes’ – dried scale insects, imported as a crimson dye. Could they have been used medicinally? Or was grana to be used to dye the king’s robes?

Another medicinal possibility is that grana was for dyeing the bed linen and curtains as part of the treatment of smallpox, in which the sickroom was swathed in red. Today we know this wasn’t so daft since red cloth filters out UV light, to reduce the production of scar tissue and to protect the eyesight of patients with smallpox or measles (these two diseases were hard to tell apart in the early stages anyway) – red light works for burns victims and would have decreased the pock marking in the case of smallpox. The medieval apothecary, like Gilbert Eastleigh in ‘The Colour of Poison’, was expected to know so much about such treatments, even if the reasons why they worked – or didn’t – were beyond the medical knowledge of the time.

N.B. One fifteenth century school book gives a list of collective nouns, including ‘a poison of treaclers’ (i.e. apothecaries who sold medicinal treacle).

[This an archive Editor's Choice post. It originally appeared on EHFA on 28 April 2016]

~~~~~~~~~~

Toni Mount earned her research Masters degree from the University of Kent in 2009 through study of a medieval medical manuscript held at the Wellcome Library in London. Recently she also completed a Diploma in Literature and Creative Writing with the Open University. Toni has published many non-fiction books, but always wanted to write a medieval thriller, and her first novel “The Colour of Poison” is the

result. Toni regularly speaks at venues throughout the UK and is the author of

several online courses available at www.medievalcourses.com.

Another medicinal possibility is that grana was for dyeing the bed linen and curtains as part of the treatment of smallpox, in which the sickroom was swathed in red. Today we know this wasn’t so daft since red cloth filters out UV light, to reduce the production of scar tissue and to protect the eyesight of patients with smallpox or measles (these two diseases were hard to tell apart in the early stages anyway) – red light works for burns victims and would have decreased the pock marking in the case of smallpox. The medieval apothecary, like Gilbert Eastleigh in ‘The Colour of Poison’, was expected to know so much about such treatments, even if the reasons why they worked – or didn’t – were beyond the medical knowledge of the time.

N.B. One fifteenth century school book gives a list of collective nouns, including ‘a poison of treaclers’ (i.e. apothecaries who sold medicinal treacle).

[This an archive Editor's Choice post. It originally appeared on EHFA on 28 April 2016]

~~~~~~~~~~

Toni Mount earned her research Masters degree from the University of Kent in 2009 through study of a medieval medical manuscript held at the Wellcome Library in London. Recently she also completed a Diploma in Literature and Creative Writing with the Open University. Toni has published many non-fiction books, but always wanted to write a medieval thriller, and her first novel “The Colour of Poison” is the

result. Toni regularly speaks at venues throughout the UK and is the author of

several online courses available at www.medievalcourses.com.