By Kim Rendfeld

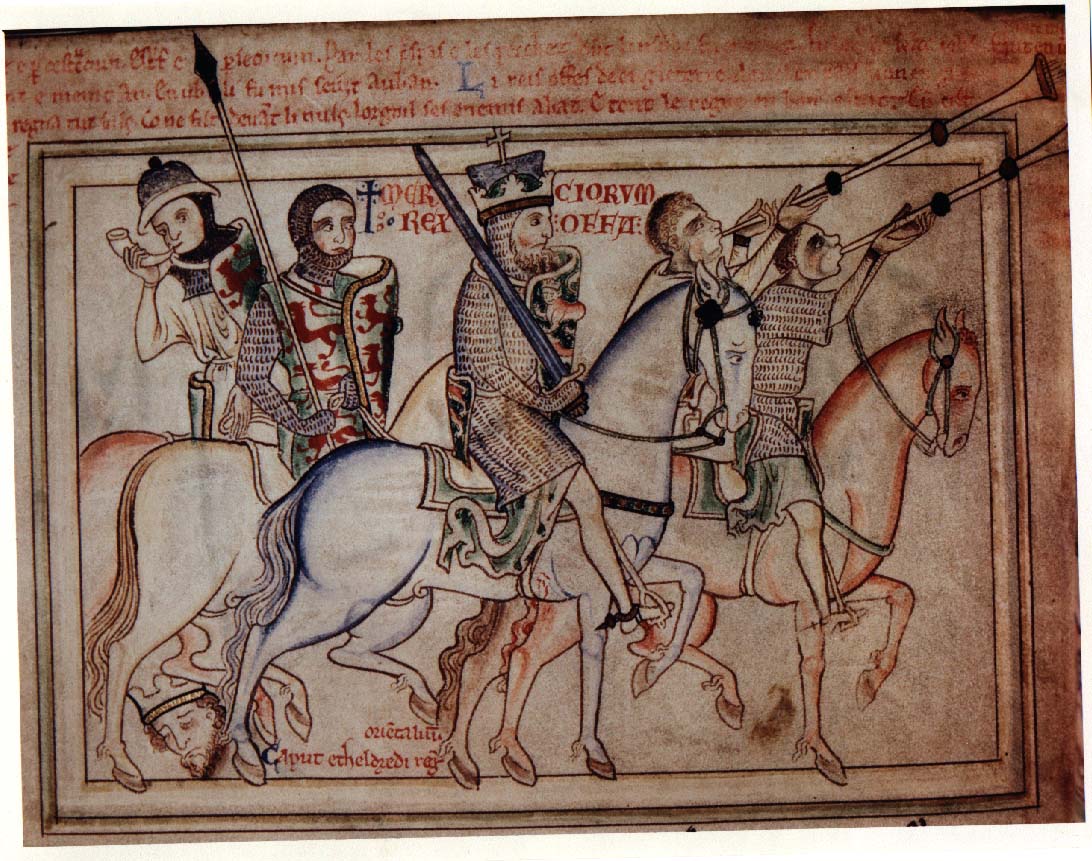

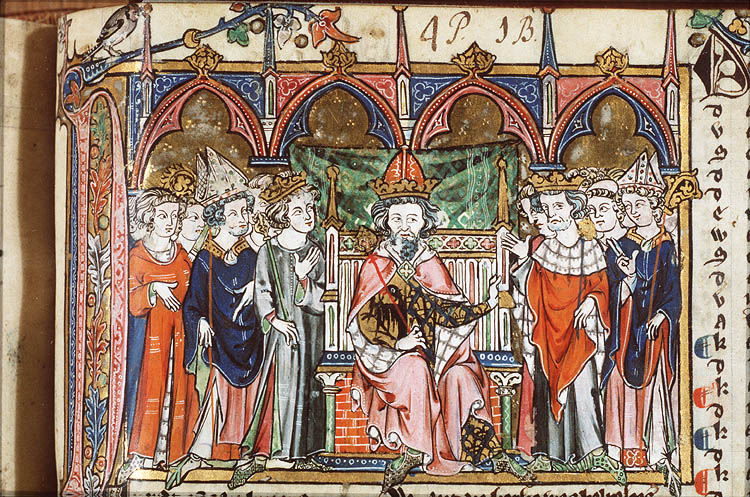

Queen Cynethryth had an exalted status during her husband’s reign and enjoyed seeing her son succeed his father, a rarity in 8th-century Mercia. Yet she would also see the dynasty she and her husband desired fall apart.

Alcuin, a scholar in Charlemagne’s court, described her as the controller of the royal household, a role akin to a treasurer and chief of staff for the kings—traditional for early medieval queens. She likely managed the properties of the many religious houses her husband founded and got papal permission to control.

Yet she had something unique: her image graces a coin minted during her husband’s reign. It was common for kings to assert their authority by having their image imprinted on currency. Cynethryth is the only known Anglo-Saxon queen to do so. Perhaps, she and her husband were inspired by the Byzantines, who minted coins with the image of Empress Mother Irene.

|

| Cynethryth penny (public domain via Wikimedia Commons) |

Cynethryth’s husband was Mercian King Offa. Although he had a reputation for ruthlessness, he knew how to play by the rules, at least when it served to his advantage. Unlike his predecessor, his kinsman Æthelbald (accused of fornication, including acts with nuns), Offa wanted the Church’s approval for his relationship with one woman—and only one woman—to ensure his offspring would inherit the crown. Offa knew that special woman, the mother of his children, should be queen of the Mercians, endowed with a royal status.

Offa apparently was a steadfast husband. He had no children born outside wedlock. True, the Church preached against sex outside marriage, but for men, it wasn’t a big deal. All a father had to do was acknowledge and support the child. Perhaps, Offa was faithful because he was fond of Cynethryth. He definitely wanted to limit the number of claimants to the throne and took the necessary, and maybe murderous, steps.

Presumably, Offa and Cynethryth wed for political reasons. We don’t know Cynethryth’s parents or her age. Her name is similar to 7th-century King Penda’s wife and daughters, so she likely came from a prestigious family. We don’t know exactly when the couple married, but her name starts to appear on charters around 770, where she identified herself as the mother of the heir to the throne, Ecgfrith.

Women in that era typically were teenagers when they married, some as young as 12 or 13. She might have been born a few years before Offa seized the throne. Æthelbald had been murdered in 757, and Offa drove away a rival shortly thereafter. Considering that Offa ruled for almost 40 years, he was probably a young man at the time. If he married around 769, he might have been in his 30s and thinking about the future.

By 770, Offa had imposed himself as overlord of Kent, taking advantage of a succession crisis there. Or, from his point of view, reasserting the Mercian rule his predecessor had established. He might have seen Cynethryth as the woman who shared his ambition for Mercia and would support his conquests. After their son’s birth, Offa continued expanding his territory into Sussex and the Hwicce.

|

| Coin with Offa's image (public domain via Wikimedia Commons) |

Who Cynethryth was as a woman is hard to say. During her lifetime, the scholar Alcuin advised Ecgfrith to learn piety from his mother. After Cynethryth’s death—long after—she is accused of being as ruthless as her husband in ordering the execution of a visiting East Anglian king. In reality, her husband might have been responsible, for political reasons. But then again, Cynethryth very well could have supported her husband. Medieval women were ambitious.

In addition to the son, Offa and Cynethryth had three daughters, Æthelburh, Eadburh, and Ælfflæd. The couple put their daughters in positions of influence. Æthelburh was an abbess who corresponded with Alcuin. Eadburh wed Beorhtric, king of Wessex. The marriage solidified Beorhtric’s claim to his throne, and the father- and son-in-law drove out Ecgberht, son of Kentish King Ealhmund and a rival for the West Saxon crown. Ælfflæd married Northumbrian King Æthelred I.

In 787, Ecgfrith was crowned co-ruler with his father, a move that ensured his succession. After Offa died on July 29, 796, Cynethryth remained at court. Her son would die before the year was over. The cause of his death remain unknown, but I suspect it was not natural causes. Her son-in-law Æthelred was murdered that year, leaving Ælfflæd a widow. We don’t know whether Cynethryth lived to see Eadburh become a widow when her husband (likely) died in battle in 802 (likely) at Ecgberht’s hand. (Decades later, Alfred the Great’s biographer, Asser, accused Eadburh of accidentally poisoning her husband while trying to kill someone else. His account is highly suspicious for many reasons, including that Alfred was Ecgberht’s grandson.)

After Ecgfrith died, Cynethryth took the veil and became abbess of Cookham (in Berkshire), one of the religious houses her husband founded and bequeathed to her. Perhaps a sign of the couple’s affection is where Cynethryth chose to retire. Cookham was close to Bedford, where Offa was buried.

|

| The Thames at Cookham (by Sebastian Ballard, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons) |

Sources

Oxford National Biography

“Offa” by S.E. Kelly

“Cynethryth” by S.E. Kelly

“Political Women in Mercia” by Pauline Stafford, Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe

Carolingian Connections: Anglo-Saxon England and Carolingian Francia, c. 750–870 by Joanna Story

~~~~~~~~~~

Kim has written two other books set in 8th century Francia. In The Cross and the Dragon, a Frankish noblewoman must contend with a jilted suitor and the fear of losing her husband (available on Amazon). In The Ashes of Heaven's Pillar, a Saxon peasant will fight for her children after losing everything else (available on Amazon). Kim's short story “Betrothed to the Red Dragon,” about Guinevere’s decision to marry Arthur, is set in early medieval Britain and available on Amazon.

Connect with Kim at on her website kimrendfeld.com, her blog, Outtakes of a Historical Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com, on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld, or follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld.