By Kim Rendfeld

About 790, Frankish King Charles (Charlemagne) had a proposition for Mercian King Offa: one of Offa’s daughters marry one of Charles’s sons.Charles likely saw this as a way to secure an alliance between a powerful kingdom in England and his vast realm—stretching from the Atlantic to east of the Rhine, from the North Sea to the Pyrenees and part of Italy. If Charles did not sire any other sons, the bridegroom, his son Charles (whom I call Karl in my books), stood to inherit all but Aquitaine and northern Italy.

Gervold, abbot of St. Wandrille, served as Charles’s envoy to work out the details. The two kings likely brought their wives into the discussions. Frankish Queen Fastrada and Mercian Queen Cynethryth were both strong-willed women. Although Karl might have also favored the marriage, but we don’t know the sentiments of the young woman involved.

In some modern eyes, princesses and other young noblewomen appear to be pawns. In medieval parents’ minds, daughters had an important role in forming the alliances and swaying their husbands to uphold her family’s interests. A husband would think his wife should convince his in-laws to side with him.

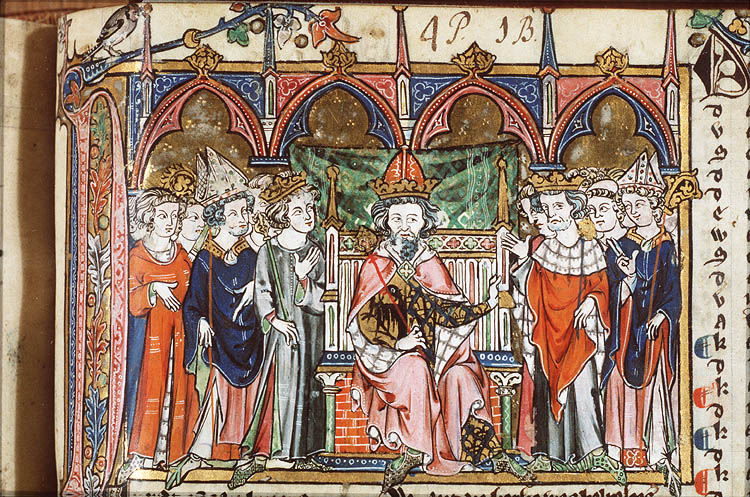

|

| Matthew Paris's 13th century tract on St. Alban (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons) |

Offa, who had seized power in 757 during a civil war after the murder of his cousin, was no exception. Although one daughter, Æthelburh, was an abbess—an influential position—another daughter, Eadburh, wed Beorhtric, king of Wessex. The marriage solidified Beorhtric’s claim to his throne, and the father- and son-in-law drove out Ecgberht, son of Kentish King Ealhmund and a rival for the West Saxon crown.

Offa had another daughter, Ælfflæd, who remained unattached in 790. Offa might have wanted her to wed a ruler in a neighboring kingdom rather than go to the continent. (She would marry Northumbrian King Æthelred I two years later.)

Offa made his own offer to Charles. He would only agree to the Frankish king’s proposition if Charles’s daughter Bertha married his son, Ecgfrith. Crowned co-ruler with his father in 787, Ecgfrith was quite the bachelor, assured of succession. Offa had, ahem, reduced the number of claimants to the throne.

But why Bertha, too young to marry at only age 11, and not her older sister, Hruodtrude, who was the marriageable age of 15? Hruodtrude had been betrothed to Byzantine Emperor Constantine, whom she never met, but that agreement fell apart a few years before.

Apparently Offa was willing to wait a couple of years as he expanded his rule into Kent. Perhaps, he thought the marriage of Charles’s second daughter to his son would remind the Kentish folk of a successful royal couple from long ago: a Merovingian princess named Bertha and Æthelberht, the most powerful Anglo-Saxon king in the late sixth century.

|

| 14th century work by Jacob van Maerlant (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons) |

Charles was not having it. Not at all. While he was willing for Offa’s daughter to come to Francia, learn the ways of the Frankish court, and benefit from the scholars there, he might not have wanted his own child to live in Mercia. He might have heard firsthand accounts of Offa’s ruthlessness and did not wish to subject Bertha to it.

Charles became angry, and that led to Mercia and Francia closing their ports to each other’s merchants.

This isn’t the first time a failed betrothal in Charles’s family had international consequences. According to the Revised Royal Frankish Annals, Constantine, furious at being refused Hruodtrude’s hand in marriage, ordered the Sicilians to attack Benevento, a duchy recently allied with Charles. (Exactly who dashed Constantine’s hopes is unclear. Both Charles and Empress Mother Irene take credit for the breakup.)

Yet I wonder if the cause of Charles’s ire was something in addition to a failed betrothal. Perhaps, Offa brought up another issue. Charles was sheltering Ecgberht, among other exiles, and that must have irked Offa, who still saw Ecgberht as a threat. Might Offa have demanded Charles surrender his guest as a condition for their children’s marriage? If that was the case, I can imagine Charles feeling indignant.

By 796, the two monarchs reconciled, and trade resumed. In an April letter from that letter, Charles calls Offa “dearest brother.”

Still, it turns out that Bertha was better off staying at home. Offa died in 796, and his son succeeded him, but Ecgfrith’s reign didn’t last even a year. He died, likely not of natural causes.

796 was a bad year for Ælfflæd, too. Her husband, Æthelred, had been a ruthless ruler, and two ealdormen took matters into their own hands and murdered him. Ælfflæd might have joined her sister Æthelburh in the cloister, a common refuge for a widowed queen. Karl himself never married. The reason remains a mystery.

Had politics not interfered with Karl and Ælfflæd’s betrothal, what kind of a couple would they have been? We’ll never know.

Sources

Charlemagne: Empire and Society, edited by Joanna Story

Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity by Rosamond McKitterick

"Carolingian Contacts" by Janet L. Nelson, from Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, edited by Michelle P. Brown, Carol A. Farr

“Offa” by S.E. Kelly, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Carolingian Connections: Anglo-Saxon England and Carolingian Francia, c. 750–870, by Joanna Story

Charlemagne: Translated Sources, P.D. King

~~~~~~~~~~

Kim has written two other books set in 8th century Francia. In The Cross and the Dragon, a Frankish noblewoman must contend with a jilted suitor and the fear of losing her husband (available on Amazon). In The Ashes of Heaven's Pillar, a Saxon peasant will fight for her children after losing everything else (available on Amazon). Kim's short story “Betrothed to the Red Dragon,” about Guinevere’s decision to marry Arthur, is set in early medieval Britain and available on Amazon.

Connect with Kim at on her website kimrendfeld.com, her blog, Outtakes of a Historical Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com, on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld, or follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld.

.jpg)

.jpg)