by Linda Root

The pages of history are crowded with tales of great passions that proved deadly when it cooled. The first example that comes to mind is Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, but there are others. In modern times, attractions between an American President and a movie star left her suicidal. However, there is another phenomenon equally tragic. We’ve all heard the trite saying Love Conquers All. The truth is, not always. History is populated by lovers whose passions never cooled, but the character traits of the one brought down the other. There is another group whose strengths and weaknesses interplayed in a manner proving fatal to them both, and a final group in which the passions or the partners were largely a construct of historians with an agenda or movie moguls who believe fiction sells better than fact.

When perusing lists of history’s greatest loves, on most lists most of the nominees are fictional or mythic. Of lists I viewed, none mentioned Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, but many included Elizabeth Bennett & Fitzwilliam Darcy, and Tristan & Isolde. Of the actual historical characters appearing on several lists such as Antony and Cleopatra, fictionalized versions prevailed over the factual. Out of the American candidates, the clear front runners were Bonnie & Clyde. I would have included Rachel and Andrew Jackson, or John and Abigail Adams, but apparently my view of historical lovers is too…historical.

Wallace Warfield Simpson and King Edward VIII came out second on one of the lists. I have not chosen them for detailed analysis because they were the subjects of my last post, but if I were to have included them, I would have had to design a category just for them.

Wallace Warfield Simpson and King Edward VIII came out second on one of the lists. I have not chosen them for detailed analysis because they were the subjects of my last post, but if I were to have included them, I would have had to design a category just for them.

It does seem that the Duchess perceived she had been used by the Duke to get him out of a job he did not want. One might agree with Sir Winston Churchill and credit her for doing modern history a colossal favor. My personal list of famous and infamous couples is purely mine. In this first segment, I chose three whose love stories I find compelling, each for different reasons.

Antony and Cleopatra – A Union of Expedience or a Tragic Love Affair?

I do not recall how old I was when I first became interested in Antony and Cleopatra, but it antedated my fascination with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. I remember dressing as Cleopatra on Halloween when I was a child in Cleveland. I would have been nine or ten. I did not know the history, but I loved the costume. Although the charismatic couple has been dead for more than two thousand years, books are still being written about them, many of them focusing on the romance and downplaying the politics. No matter how their stories are shelved in the bookstores, all of them appear to contain a large amount of fiction. The reason is, most of the early historians were subsidized by politicians.

If we accept the recent analysis of Adrian[i] Goldsworthy in his recent book Antony and Cleopatra, we may conclude that Liz and Dick, not Antony and Cleopatra were the only star-crossed lovers on the 1960’s movie set.[ii][1] The characters they portrayed were political shakers and movers. Their romance was coincidental to the power play, a natural result of the late hours they spent together endeavoring to redraw the map of the ancient world.

According to Goldsmith, their attraction was indeed political. If Cleopatra had been in anyone’s thrall, it would have been Caesar. She and Antony were allies in a civil war they lost. Goldsmith also draws attention to the fact that in lists of formidable ancient rulers (i.e., those who ruled before the Fall of Rome) Cleopatra is often the only female mentioned.

Other modern biographers of Cleopatra, especially Stacy Shiff, in her Cleopatra: A Life[2], suggest it was Caesar, not Antony, who was the Queen of Egypt’s soul mate. They had compatible aspirations and philosophies, and there is little doubt they had a passionate love affair. Antony, to put it in a cinematic context, was Cleopatra’s Eddie Fisher, following after the death of Taylor’s personal Caesar, the cinemascope tycoon Michael Todd. The historic coupling of the actual Antony and Cleopatra was a partnership of two ambitious people endeavoring to grab what they could, and later, as Octavian’s power increased, seeking to retain what portion of the ancient world remained in their grasp. This does not mean the relationship was asexual. Three children prove otherwise. The twins Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios were conceived during their first meeting. A third child, Ptolemy Philadelphus was born four years later, when Antony returned to Egypt from Rome to secure a power base there. On the second trip, the couple married in an Egyptian rite of a questionable effect since Antony was already married to his rival Octavian’s sister. William Shakespeare and George Bernard Shaw’s characters are artful literary constructs. Politics, not romance, was the passion making the Roman soldier and the ethnic Greek Queen of Egypt partners.

At the time Caesar came into Cleopatra’s life, she was a young girl in a power struggle with her brother Ptolemy. The Macedonian Greek Ptolemy dynasty’s hold on Egypt was tenuous at best. Caesar’s arrival stabilized the country. He tried to negotiate a peace between the warring siblings, but that was not easily done. Cleopatra's brother was having none of it. There is apparently more than a hint of truth in the tale of Cleopatra having herself rolled into a rug and delivered to Caesar’s chambers to make her pitch. It is an example of her ingenuity, and it worked.

When Caesar was assassinated, Antony was the muscle on the scene. Unbiased accounts support a view finding him a better senator than a military leader and far less intelligent than the woman with whom he co-ruled Egypt for three years after his falling out with Caesar’s son and political heir Octavian until he and Cleopatra were defeated in the naval battle of Actium. Rather than face humiliation, and possibly believing Cleopatra was already dead, Antony stabbed himself in the heart. Some historians report Octavian had him transported to Cleopatra, to die in her arms. Cleopatra's suicide a few days later was just as likely an act to avoid capture and display in a victory parade as in despair over Antony’s death.

Painting her as a harlot who was utterly dependent on the powerful men she had seduced was the practice among Roman historians, and was largely propaganda inspired by Octavian and his supporters. Although Cleopatra’s expertise as a military commander and a noteworthy a naval strategist should have been acceptable to Elizabethan audiences and the English Queen, those were not the traits stressed by Shakespeare’s Cleopatra, who modeled his queen on Plutarch’s works. Thus, it is the Shakespearean seductress whose image has endured.

A few recent historians have dared to take an unbiased look at her. To them, she appears as the most capable leader of the romantic pair. Antony was no Caesar. Even the Roman hierarchy was willing to concede that she died well, like a soldier. It is believed Octavian supervised her burial in a secret tomb she shares with Antony, and stage-managed the drama of her death. Until modern times, suicide was considered a noble death. While poison is likely, Octavian liked the imagery of the snake bite better, and Octavian, who became the mighty Caesar Augustus, ruled. At least one of her biographers declares Cleopatra too much a pragmatist to have left her fate to anything as uncertain as a snake bite. New technologies have sparked current efforts to find Cleopatra’s tomb. One hopes she does not sleep alone.

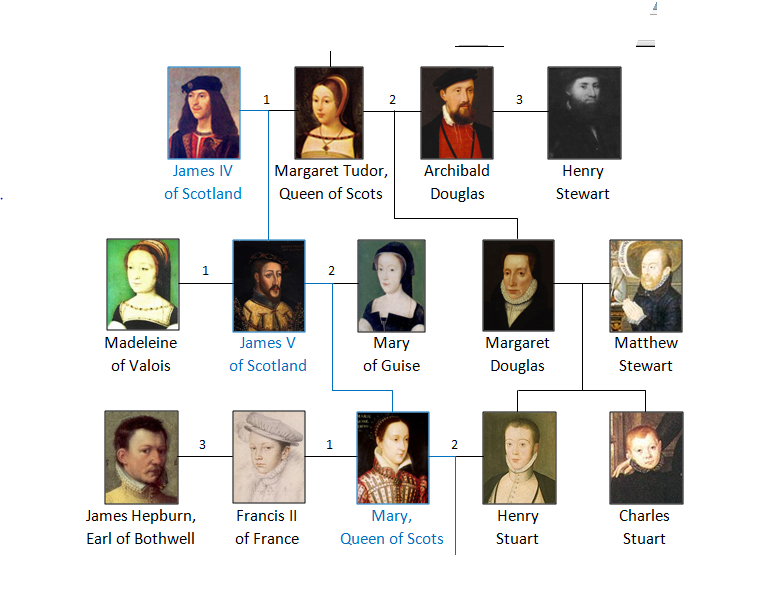

Marie Stuart, Queen of Scots, and James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell: A Mismatched Pair

Recently, on a Facebook page devoted to Victoria and Albert and their children, a member proposed a thread on the Queen of Scots, particularly dealing with her guilt or innocence of the murder of her second husband Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. Her relationship with her third husband, James Hepburn, best known by the title of his earldom, ‘Bothwell’ became a hot topic. I doubt anyone could have predicted the high degree of participation or the passions of the debates that followed. Arguments became so heated there was talk of closing down the thread. The discussion was finally upstaged by an announcement in the Scottish press claiming a scholarly tribunal had ‘cleared’ the queen of guilt in her second husband’s murder.

Marie Stuart’s husband and consort, King Henry Stuart, aka Darnley, was found dead at a bizarre crimes scene in an Edinburgh suburb, on February 10, 1567. He was lodging there while recovering from a bout of tertiary syphilis. His illness was being treated by his supposedly doting wife. But was she a sympathetic caregiver or a deceiver who was conspiring with a new lover, Bothwell, to have Darnley killed?

Thanks to the factionalism in Marie Stuart’s Scotland, and powers unfriendly to the queen, almost four hundred fifty years later, a debate still rages as to whether she had her second husband murdered to make way for the third. I doubt a panel convened by the Royal Society of Edinburgh and reported in the Daily Mail will silence the discord. [3] The queen did little to stifle the scandal when she chose Hepburn as her champion and confidante. Hepburn was a committed Anglophobe. With him guiding the queen through the political quagmire that followed Darnley’s murder, there was no question of Elizabeth promoting a union of the crowns by making the Queen of Scots her heir. Unfortunately for Marie, her formidable advisors William Maitland of Lethington and her brother James, Earl of Moray, were only a few of the high placed Scots who had staked their futures with England and Elizabeth. On the other hand, Bothwell was a reiver warlord of considerable military prowess and a large following, but he was also an ardent Anglophobe. He was inordinately intelligent and highly educated, not the sort of man to take advice from politicians. However, at the time of the queen’s son’s Baptism in December 1566, Darnley’s behavior had become unpredictable and dangerous, as the saying goes, politics makes strange bedfellows Such unions rarely last. After Darnley’s murder late in the winter of 1567, Bothwell and the queen closeted themselves for long hours in the queen’s private apartments discussing the governance of the nation. Bothwell began holding audiences and bestowing grants and favors as if he were the king. The queen gave her new confidante her dead husband’s suite of gilded armor.

In spite of the scandal surrounding the queen’s abbreviated period of mourning and her obvious preference for Hepburn, when Parliament opened in April, there was yet no sign of the open hostility that had surrounded Darnley before the queen’s second marriage. After the last session of Parliament, Hepburn hosted a dinner party for the leading parliamentarians, including many high ranking peers and members of the clergy. The site of the event may or may not have been at Ainslie’s Tavern, but historians refer to the accord reached at the end of the evening as the AinslieTavern Bond. A large majority of Bothwell’s dinner guests, including eight bishops, nine earls, and seven lords, signed it[4]. When and where and under what circumstances is unclear. The queen’s brother James, Earl of Moray, who had led a rebellion when the queen married Darnley, is named as one of the signatories. However, according to historian John Guy[5], Moray was out of the country and could not have signed it. The Bishop of Ross and Lord Elphinstone apparently left early to avoid being pressured, and Sir William Kirkcaldy of Grange, who hated Bothwell, declined the invitation. [6] According to Guy,[7] Argyll refused to sign the bond and, like Kirkcaldy, Maitland and Atholl did not attend the dinner, although they may have signed a copy later. Like many of the operative documents during the last days of Marie Stuart’s personal rule, the original bond has disappeared. The instrument urged the queen to take Bothwell for her third husband.

The events of the next few days are puzzling and pivotal as to what followed. According to Antonia Fraser, [8] on the day after the signing of the bond, Bothwell, Bellenden and Maitland of Lethington visited the Queen at Seton House and delivered the bond to the queen, who was in seclusion there. Guy, however, reports an incident at Holyrood in which Bothwell incurred the wrath of the garrison on a issue of nonpayment of wages, and the queen intervened and paid them from her little-embroidered purse. Hepburn was upstaged and displeased. In any event, the queen later stated that April 20th was the date when Bothwell first plied his suit. All parties agree she refused, on grounds it might tarnish her honor due to the lingering questions concerning Bothwell’s role in Darnley’s death. It may well be that both versions are true.

If Bothwell took Maitland to Seton house to present the bond, it would have been solely to give his presentation credibility. Although, in March, when Bothwell was tried and acquitted of Darnley’s murder before a highly biased court, Hepburn had selected Maitland to escort him to the hearings, he and Maitland were never friends. Their joint trip to Seton House may have been a coincidence since the Queen and Maitland were planning a trip to Stirling the net day ostensibly to collect the prince. In either case, the queen’s rejection of Bothwell’s proposal in Maitland’s presence would have enraged a prideful man like Bothwell and might explain his actions four days later when he waylaid the Queen’s party on its way home. There are other indications the queen returned to Holyrood with Maitland to prepare for her trip to Stirling the following day, April 21, 1567, which makes both Fraser’s and Guy’s versions feasible. Both events, taken together, would explain why at day’s end on April 20th Bothwell would have been seething.

By early spring of 1567, the queen had grown increasingly dependent on the man who had been tried and acquitted of her husband Darnley’s murder, but she still had the determination to refuse him her hand in marriage or let him alienate her palace guard. Yet, the puzzle then and a mystery even now is whether they were lovers before April 24, 1567, the day Hepburn hijacked the queen and carried her off to Dunbar. In a nutshell, was she so in love with him she was unable to see the political implications of acknowledging him as her lover, or was she responding as a classic rape victim? On this point, I have the audacity to disagree with my hero, historian John Guy, based on my expertise as a prosecutor dealing with victims of sexual assault. While my analysis is by no means dispositive, my personal training and experience, her behavior is consistent with that of a rape victim. Even in the last decades of the Twentieth Century when new Rape Shield Laws were enacted in the United States, the bold, empowered victim ready to publically wreck vengeance on her assailants by pointing her finger and calling sexual assault a rape was the exception, not the rule.

After April 24th, the queen acted very much like a woman who had been humiliated in a very personal way. She cried at the slightest provocation, but she also hardened, adopting the crude language for which Bothwell was known. At times, she called for a dagger so she could kill herself. She was given to bouts of both histrionics and hysterics, not at all the woman whose personality had been shaped by the cool, politically astute Diane de Poitiers, and whose public imagine and personal belief was as one ordained a queen by God. Whatever happened to Marie Stuart on April 24th changed her, and it does not sound like love, or as some writers have suggested, the attainment of her first orgasm. There is, however, another explanation consistent with the queen’s behavior in the past which adds a new dimension to the mystery.

Due to his past loyalty and willingness to pursue both the queen’s mother Marie de Guise’s and her own agenda, might the Queen of Scots have come to look upon the bold Border warlord as her champion? Certainly, she trusted him. The year before when she traveled to Alloa to recuperate from a difficult childbirth, she left her son in Bothwell’s care at Edinburgh Castle. Guy’s account and others suggest at least a portion of the events of April 24th were contrived. There were rumors the queen’s trip to Stirling to retrieve custody of Prince James and Bothwell’s side trip to the Borders to enforce the law were part of a two-pronged scheme to shift the guardianship of the prince from the Earl of Mar to Bothwell, who would spirit the infant off to Dunbar. Guy and others, including Sir James Melville, who was there, believe the queen’s show of surprise when Bothwell and a force of 800 intercepted her entourage. She apparently dispatched at least one rider to capital to sound the alarm.

Due to his past loyalty and willingness to pursue both the queen’s mother Marie de Guise’s and her own agenda, might the Queen of Scots have come to look upon the bold Border warlord as her champion? Certainly, she trusted him. The year before when she traveled to Alloa to recuperate from a difficult childbirth, she left her son in Bothwell’s care at Edinburgh Castle. Guy’s account and others suggest at least a portion of the events of April 24th were contrived. There were rumors the queen’s trip to Stirling to retrieve custody of Prince James and Bothwell’s side trip to the Borders to enforce the law were part of a two-pronged scheme to shift the guardianship of the prince from the Earl of Mar to Bothwell, who would spirit the infant off to Dunbar. Guy and others, including Sir James Melville, who was there, believe the queen’s show of surprise when Bothwell and a force of 800 intercepted her entourage. She apparently dispatched at least one rider to capital to sound the alarm.

However, later in the encounter, she and Bothwell spoke privately, and thereafter, she instructed her escort of thirty armed men to stand down. It is possible that after two days of simmering over the humiliation of a rejected suitor, the earl had changed the game plan and instead of a peaceful rendezvous to take custody of the prince, he decided to go for the higher stakes by carrying her off and raping her? A young woman with the background of the Queen would have been devastated, not because she did not love James Hepburn, but because she did.

Yet, there is no credible evidence they were lovers before that fatal week in April. Fables identifying them as long-time conniving paramours are a construct of Marie Stuart’s political and religious critics. A confession made by Bothwell toward the end his life indicating the queen was blameless of Darnley’s murder is often cited as evidence of his fidelity and love, but they are equally consistent with a man seeking to unburden himself of heavy guilt. In my analysis, the combination of his pugnacious arrogance and the queen’s naive obsession with honor combined to ruin them both. Regardless of whether what occurred between them at Dunbar was a rape or a lover’s tryst, without having the prince in their custody and control, they were doomed.

The banner flown by the Lords of the Congregation at Carberry was one of the factors that gave the day to the Lords. Large numbers of the Queen's army deserted.

The banner flown by the Lords of the Congregation at Carberry was one of the factors that gave the day to the Lords. Large numbers of the Queen's army deserted.

The queen surrendered to Kirkcaldy of Grange while Bothwell (shown in the background of the watercolor) rode away. They never saw one another again.

John and Sarah Churchill, the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough: A Love Story

Not a single list I reviewed mentioned John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough and his Duchess Sarah Jennings Churchill, although there was a dynamic love that endured long after the Duke’s death. Marlborough was every bit the military hero Henry V had been at Agincourt. He came close to handing France to Queen Anne on a platter.

But he was only half of a dynamic partnership that in almost any light comes across as an unlikely love story. Both John Churchill and Sarah Jennings were incredibly ambitious people, and each of them was looking to make an advantageous marriage at the time they met and quite accidentally, fell in love. Churchill had risen from a mere page to become a favorite of the Duke of York, later James II. Sarah came from lower tier aristocracy, but became an intimate of Princess Anne. Although neither had the social status to be a likely candidate for marriage at the time they met, they simply found one another irresistible. Sarah’s parents had urged her to hold out for someone rich.

When Sarah was an equal partner, theirs was a winning team. John was the military strategist and statesman. Sarah was the politician and courtier, both at the Court of James II, and later, at the courts of William & Mary and later, Queen Anne.

It was during Queen Anne’s reign that Sarah Churchill became the power behind the throne. Unfortunately, she did not wield her power graciously. While her husband was in Europe waging war, his duchess was heavy-handed in her management of the Queen and at times was a notorious bully. Sarah was incredibly bright and spared no words in letting Anne know which of them was the superior intellect. She also was an avid Whig, who made every prominent Tory her personal enemy. As time went on, Sarah overplayed her hand with the queen and Marlborough paid the price. Queen Anne withdrew her support of Marlborough’s military efforts on the eve of a complete capitulation of the opposition, and Marlborough was recalled. His political enemies lodged trumped-up charges of embezzlement against him over a government contract for bread, what today would be called a kickback. Soon thereafter, The Queen was so embittered by Sarah’s insensitivity over the death of her son that she and her ministers reneged on their gift of funds to complete the Marlborough’s mammoth construction project near Woodstock, Blenheim Palace.

In the wake of a campaign to discredit the duke, the Marlboroughs withdrew not just from the court, but from the country. They lived in high style in the German principalities and the Netherlands, where the Duke’s military genius and statesmanship during the War of the Spanish Succession was a legend. Even the French king held him in high esteem.

When Queen Anne died childless and the crown passed to the House of Hanover, the Churchills were again in favor at home in England. King George and Marlborough had fought side by side and were good friends. Nevertheless, the Duke would probably have been happy staying away, but Sarah wanted to go home. However, even in an England ruled by the House of Hanover, Sarah’s strong will and irascible temper alienated Queen Caroline. They devoted most of their attention to managing their properties. When the Duke died, Sarah Jennings Churchill was one of Europe’s wealthiest women. She completed construction of Blenheim Castle after her husband’s death and made life close to unbearable for its architect.

Even in her advanced age, she was plagued by suitors young enough to be her son. She is said to have spurned one of them in the language quoted by Sir Winston Churchill in his famed biography[9]:

While Sarah’s outspoken politics and rude treatment of the Queen prevented her husband from achieving total domination of Europe, he is widely credited for raising England from a minor to major power.[10] There is no doubt his success was aided by the support he received from Queen Anne at the insistence of his Duchess. In conclusion, there is more to the life and times of the Duke of Marlborough than politics and romance. While I was in college in the late 50’s, I discovered John and Sarah Churchill and fought the battle of Blenheim on my cot. For those who have the slightest interest in military history, it is worthy of a reenactment.

Thank you for joining me in a brief glimpse of three of history’s many great love stories. I predict there will be more to come.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Linda Root is the author of six historical novels set in the late 16th and early seventeenth century, The First Marie and the Queen of Scots, (2011) and The Last Knight and the Queen of Scots (2013), both large historicals, and the Legacy of the Queen of Scots Suite consisting of four books to date and the fifth coming in November. She also writes historical fantasy under the name J.D. Root. Root is a former major crimes prosecutor living in the high desert above Palm Springs with husband Chris and two Alaskan malamutes Maxx and Maya. Visit her Visit her author’s page.

Linda Root is the author of six historical novels set in the late 16th and early seventeenth century, The First Marie and the Queen of Scots, (2011) and The Last Knight and the Queen of Scots (2013), both large historicals, and the Legacy of the Queen of Scots Suite consisting of four books to date and the fifth coming in November. She also writes historical fantasy under the name J.D. Root. Root is a former major crimes prosecutor living in the high desert above Palm Springs with husband Chris and two Alaskan malamutes Maxx and Maya. Visit her Visit her author’s page.

Artwork from Wikimedia Commons, original art by Linda Root.

The pages of history are crowded with tales of great passions that proved deadly when it cooled. The first example that comes to mind is Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, but there are others. In modern times, attractions between an American President and a movie star left her suicidal. However, there is another phenomenon equally tragic. We’ve all heard the trite saying Love Conquers All. The truth is, not always. History is populated by lovers whose passions never cooled, but the character traits of the one brought down the other. There is another group whose strengths and weaknesses interplayed in a manner proving fatal to them both, and a final group in which the passions or the partners were largely a construct of historians with an agenda or movie moguls who believe fiction sells better than fact.

When perusing lists of history’s greatest loves, on most lists most of the nominees are fictional or mythic. Of lists I viewed, none mentioned Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, but many included Elizabeth Bennett & Fitzwilliam Darcy, and Tristan & Isolde. Of the actual historical characters appearing on several lists such as Antony and Cleopatra, fictionalized versions prevailed over the factual. Out of the American candidates, the clear front runners were Bonnie & Clyde. I would have included Rachel and Andrew Jackson, or John and Abigail Adams, but apparently my view of historical lovers is too…historical.

Wallace Warfield Simpson and King Edward VIII came out second on one of the lists. I have not chosen them for detailed analysis because they were the subjects of my last post, but if I were to have included them, I would have had to design a category just for them.

Wallace Warfield Simpson and King Edward VIII came out second on one of the lists. I have not chosen them for detailed analysis because they were the subjects of my last post, but if I were to have included them, I would have had to design a category just for them.It does seem that the Duchess perceived she had been used by the Duke to get him out of a job he did not want. One might agree with Sir Winston Churchill and credit her for doing modern history a colossal favor. My personal list of famous and infamous couples is purely mine. In this first segment, I chose three whose love stories I find compelling, each for different reasons.

Antony and Cleopatra – A Union of Expedience or a Tragic Love Affair?

I do not recall how old I was when I first became interested in Antony and Cleopatra, but it antedated my fascination with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. I remember dressing as Cleopatra on Halloween when I was a child in Cleveland. I would have been nine or ten. I did not know the history, but I loved the costume. Although the charismatic couple has been dead for more than two thousand years, books are still being written about them, many of them focusing on the romance and downplaying the politics. No matter how their stories are shelved in the bookstores, all of them appear to contain a large amount of fiction. The reason is, most of the early historians were subsidized by politicians.

If we accept the recent analysis of Adrian[i] Goldsworthy in his recent book Antony and Cleopatra, we may conclude that Liz and Dick, not Antony and Cleopatra were the only star-crossed lovers on the 1960’s movie set.[ii][1] The characters they portrayed were political shakers and movers. Their romance was coincidental to the power play, a natural result of the late hours they spent together endeavoring to redraw the map of the ancient world.

According to Goldsmith, their attraction was indeed political. If Cleopatra had been in anyone’s thrall, it would have been Caesar. She and Antony were allies in a civil war they lost. Goldsmith also draws attention to the fact that in lists of formidable ancient rulers (i.e., those who ruled before the Fall of Rome) Cleopatra is often the only female mentioned.

Other modern biographers of Cleopatra, especially Stacy Shiff, in her Cleopatra: A Life[2], suggest it was Caesar, not Antony, who was the Queen of Egypt’s soul mate. They had compatible aspirations and philosophies, and there is little doubt they had a passionate love affair. Antony, to put it in a cinematic context, was Cleopatra’s Eddie Fisher, following after the death of Taylor’s personal Caesar, the cinemascope tycoon Michael Todd. The historic coupling of the actual Antony and Cleopatra was a partnership of two ambitious people endeavoring to grab what they could, and later, as Octavian’s power increased, seeking to retain what portion of the ancient world remained in their grasp. This does not mean the relationship was asexual. Three children prove otherwise. The twins Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios were conceived during their first meeting. A third child, Ptolemy Philadelphus was born four years later, when Antony returned to Egypt from Rome to secure a power base there. On the second trip, the couple married in an Egyptian rite of a questionable effect since Antony was already married to his rival Octavian’s sister. William Shakespeare and George Bernard Shaw’s characters are artful literary constructs. Politics, not romance, was the passion making the Roman soldier and the ethnic Greek Queen of Egypt partners.

At the time Caesar came into Cleopatra’s life, she was a young girl in a power struggle with her brother Ptolemy. The Macedonian Greek Ptolemy dynasty’s hold on Egypt was tenuous at best. Caesar’s arrival stabilized the country. He tried to negotiate a peace between the warring siblings, but that was not easily done. Cleopatra's brother was having none of it. There is apparently more than a hint of truth in the tale of Cleopatra having herself rolled into a rug and delivered to Caesar’s chambers to make her pitch. It is an example of her ingenuity, and it worked.

When Caesar was assassinated, Antony was the muscle on the scene. Unbiased accounts support a view finding him a better senator than a military leader and far less intelligent than the woman with whom he co-ruled Egypt for three years after his falling out with Caesar’s son and political heir Octavian until he and Cleopatra were defeated in the naval battle of Actium. Rather than face humiliation, and possibly believing Cleopatra was already dead, Antony stabbed himself in the heart. Some historians report Octavian had him transported to Cleopatra, to die in her arms. Cleopatra's suicide a few days later was just as likely an act to avoid capture and display in a victory parade as in despair over Antony’s death.

Painting her as a harlot who was utterly dependent on the powerful men she had seduced was the practice among Roman historians, and was largely propaganda inspired by Octavian and his supporters. Although Cleopatra’s expertise as a military commander and a noteworthy a naval strategist should have been acceptable to Elizabethan audiences and the English Queen, those were not the traits stressed by Shakespeare’s Cleopatra, who modeled his queen on Plutarch’s works. Thus, it is the Shakespearean seductress whose image has endured.

A few recent historians have dared to take an unbiased look at her. To them, she appears as the most capable leader of the romantic pair. Antony was no Caesar. Even the Roman hierarchy was willing to concede that she died well, like a soldier. It is believed Octavian supervised her burial in a secret tomb she shares with Antony, and stage-managed the drama of her death. Until modern times, suicide was considered a noble death. While poison is likely, Octavian liked the imagery of the snake bite better, and Octavian, who became the mighty Caesar Augustus, ruled. At least one of her biographers declares Cleopatra too much a pragmatist to have left her fate to anything as uncertain as a snake bite. New technologies have sparked current efforts to find Cleopatra’s tomb. One hopes she does not sleep alone.

Marie Stuart, Queen of Scots, and James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell: A Mismatched Pair

Recently, on a Facebook page devoted to Victoria and Albert and their children, a member proposed a thread on the Queen of Scots, particularly dealing with her guilt or innocence of the murder of her second husband Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. Her relationship with her third husband, James Hepburn, best known by the title of his earldom, ‘Bothwell’ became a hot topic. I doubt anyone could have predicted the high degree of participation or the passions of the debates that followed. Arguments became so heated there was talk of closing down the thread. The discussion was finally upstaged by an announcement in the Scottish press claiming a scholarly tribunal had ‘cleared’ the queen of guilt in her second husband’s murder.

Marie Stuart’s husband and consort, King Henry Stuart, aka Darnley, was found dead at a bizarre crimes scene in an Edinburgh suburb, on February 10, 1567. He was lodging there while recovering from a bout of tertiary syphilis. His illness was being treated by his supposedly doting wife. But was she a sympathetic caregiver or a deceiver who was conspiring with a new lover, Bothwell, to have Darnley killed?

Thanks to the factionalism in Marie Stuart’s Scotland, and powers unfriendly to the queen, almost four hundred fifty years later, a debate still rages as to whether she had her second husband murdered to make way for the third. I doubt a panel convened by the Royal Society of Edinburgh and reported in the Daily Mail will silence the discord. [3] The queen did little to stifle the scandal when she chose Hepburn as her champion and confidante. Hepburn was a committed Anglophobe. With him guiding the queen through the political quagmire that followed Darnley’s murder, there was no question of Elizabeth promoting a union of the crowns by making the Queen of Scots her heir. Unfortunately for Marie, her formidable advisors William Maitland of Lethington and her brother James, Earl of Moray, were only a few of the high placed Scots who had staked their futures with England and Elizabeth. On the other hand, Bothwell was a reiver warlord of considerable military prowess and a large following, but he was also an ardent Anglophobe. He was inordinately intelligent and highly educated, not the sort of man to take advice from politicians. However, at the time of the queen’s son’s Baptism in December 1566, Darnley’s behavior had become unpredictable and dangerous, as the saying goes, politics makes strange bedfellows Such unions rarely last. After Darnley’s murder late in the winter of 1567, Bothwell and the queen closeted themselves for long hours in the queen’s private apartments discussing the governance of the nation. Bothwell began holding audiences and bestowing grants and favors as if he were the king. The queen gave her new confidante her dead husband’s suite of gilded armor.

In spite of the scandal surrounding the queen’s abbreviated period of mourning and her obvious preference for Hepburn, when Parliament opened in April, there was yet no sign of the open hostility that had surrounded Darnley before the queen’s second marriage. After the last session of Parliament, Hepburn hosted a dinner party for the leading parliamentarians, including many high ranking peers and members of the clergy. The site of the event may or may not have been at Ainslie’s Tavern, but historians refer to the accord reached at the end of the evening as the AinslieTavern Bond. A large majority of Bothwell’s dinner guests, including eight bishops, nine earls, and seven lords, signed it[4]. When and where and under what circumstances is unclear. The queen’s brother James, Earl of Moray, who had led a rebellion when the queen married Darnley, is named as one of the signatories. However, according to historian John Guy[5], Moray was out of the country and could not have signed it. The Bishop of Ross and Lord Elphinstone apparently left early to avoid being pressured, and Sir William Kirkcaldy of Grange, who hated Bothwell, declined the invitation. [6] According to Guy,[7] Argyll refused to sign the bond and, like Kirkcaldy, Maitland and Atholl did not attend the dinner, although they may have signed a copy later. Like many of the operative documents during the last days of Marie Stuart’s personal rule, the original bond has disappeared. The instrument urged the queen to take Bothwell for her third husband.

The events of the next few days are puzzling and pivotal as to what followed. According to Antonia Fraser, [8] on the day after the signing of the bond, Bothwell, Bellenden and Maitland of Lethington visited the Queen at Seton House and delivered the bond to the queen, who was in seclusion there. Guy, however, reports an incident at Holyrood in which Bothwell incurred the wrath of the garrison on a issue of nonpayment of wages, and the queen intervened and paid them from her little-embroidered purse. Hepburn was upstaged and displeased. In any event, the queen later stated that April 20th was the date when Bothwell first plied his suit. All parties agree she refused, on grounds it might tarnish her honor due to the lingering questions concerning Bothwell’s role in Darnley’s death. It may well be that both versions are true.

If Bothwell took Maitland to Seton house to present the bond, it would have been solely to give his presentation credibility. Although, in March, when Bothwell was tried and acquitted of Darnley’s murder before a highly biased court, Hepburn had selected Maitland to escort him to the hearings, he and Maitland were never friends. Their joint trip to Seton House may have been a coincidence since the Queen and Maitland were planning a trip to Stirling the net day ostensibly to collect the prince. In either case, the queen’s rejection of Bothwell’s proposal in Maitland’s presence would have enraged a prideful man like Bothwell and might explain his actions four days later when he waylaid the Queen’s party on its way home. There are other indications the queen returned to Holyrood with Maitland to prepare for her trip to Stirling the following day, April 21, 1567, which makes both Fraser’s and Guy’s versions feasible. Both events, taken together, would explain why at day’s end on April 20th Bothwell would have been seething.

By early spring of 1567, the queen had grown increasingly dependent on the man who had been tried and acquitted of her husband Darnley’s murder, but she still had the determination to refuse him her hand in marriage or let him alienate her palace guard. Yet, the puzzle then and a mystery even now is whether they were lovers before April 24, 1567, the day Hepburn hijacked the queen and carried her off to Dunbar. In a nutshell, was she so in love with him she was unable to see the political implications of acknowledging him as her lover, or was she responding as a classic rape victim? On this point, I have the audacity to disagree with my hero, historian John Guy, based on my expertise as a prosecutor dealing with victims of sexual assault. While my analysis is by no means dispositive, my personal training and experience, her behavior is consistent with that of a rape victim. Even in the last decades of the Twentieth Century when new Rape Shield Laws were enacted in the United States, the bold, empowered victim ready to publically wreck vengeance on her assailants by pointing her finger and calling sexual assault a rape was the exception, not the rule.

After April 24th, the queen acted very much like a woman who had been humiliated in a very personal way. She cried at the slightest provocation, but she also hardened, adopting the crude language for which Bothwell was known. At times, she called for a dagger so she could kill herself. She was given to bouts of both histrionics and hysterics, not at all the woman whose personality had been shaped by the cool, politically astute Diane de Poitiers, and whose public imagine and personal belief was as one ordained a queen by God. Whatever happened to Marie Stuart on April 24th changed her, and it does not sound like love, or as some writers have suggested, the attainment of her first orgasm. There is, however, another explanation consistent with the queen’s behavior in the past which adds a new dimension to the mystery.

Due to his past loyalty and willingness to pursue both the queen’s mother Marie de Guise’s and her own agenda, might the Queen of Scots have come to look upon the bold Border warlord as her champion? Certainly, she trusted him. The year before when she traveled to Alloa to recuperate from a difficult childbirth, she left her son in Bothwell’s care at Edinburgh Castle. Guy’s account and others suggest at least a portion of the events of April 24th were contrived. There were rumors the queen’s trip to Stirling to retrieve custody of Prince James and Bothwell’s side trip to the Borders to enforce the law were part of a two-pronged scheme to shift the guardianship of the prince from the Earl of Mar to Bothwell, who would spirit the infant off to Dunbar. Guy and others, including Sir James Melville, who was there, believe the queen’s show of surprise when Bothwell and a force of 800 intercepted her entourage. She apparently dispatched at least one rider to capital to sound the alarm.

Due to his past loyalty and willingness to pursue both the queen’s mother Marie de Guise’s and her own agenda, might the Queen of Scots have come to look upon the bold Border warlord as her champion? Certainly, she trusted him. The year before when she traveled to Alloa to recuperate from a difficult childbirth, she left her son in Bothwell’s care at Edinburgh Castle. Guy’s account and others suggest at least a portion of the events of April 24th were contrived. There were rumors the queen’s trip to Stirling to retrieve custody of Prince James and Bothwell’s side trip to the Borders to enforce the law were part of a two-pronged scheme to shift the guardianship of the prince from the Earl of Mar to Bothwell, who would spirit the infant off to Dunbar. Guy and others, including Sir James Melville, who was there, believe the queen’s show of surprise when Bothwell and a force of 800 intercepted her entourage. She apparently dispatched at least one rider to capital to sound the alarm.However, later in the encounter, she and Bothwell spoke privately, and thereafter, she instructed her escort of thirty armed men to stand down. It is possible that after two days of simmering over the humiliation of a rejected suitor, the earl had changed the game plan and instead of a peaceful rendezvous to take custody of the prince, he decided to go for the higher stakes by carrying her off and raping her? A young woman with the background of the Queen would have been devastated, not because she did not love James Hepburn, but because she did.

Yet, there is no credible evidence they were lovers before that fatal week in April. Fables identifying them as long-time conniving paramours are a construct of Marie Stuart’s political and religious critics. A confession made by Bothwell toward the end his life indicating the queen was blameless of Darnley’s murder is often cited as evidence of his fidelity and love, but they are equally consistent with a man seeking to unburden himself of heavy guilt. In my analysis, the combination of his pugnacious arrogance and the queen’s naive obsession with honor combined to ruin them both. Regardless of whether what occurred between them at Dunbar was a rape or a lover’s tryst, without having the prince in their custody and control, they were doomed.

The banner flown by the Lords of the Congregation at Carberry was one of the factors that gave the day to the Lords. Large numbers of the Queen's army deserted.

The banner flown by the Lords of the Congregation at Carberry was one of the factors that gave the day to the Lords. Large numbers of the Queen's army deserted. The queen surrendered to Kirkcaldy of Grange while Bothwell (shown in the background of the watercolor) rode away. They never saw one another again.

|

| Linda Root from The Last Knight and the Queen of Scots |

John and Sarah Churchill, the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough: A Love Story

Not a single list I reviewed mentioned John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough and his Duchess Sarah Jennings Churchill, although there was a dynamic love that endured long after the Duke’s death. Marlborough was every bit the military hero Henry V had been at Agincourt. He came close to handing France to Queen Anne on a platter.

But he was only half of a dynamic partnership that in almost any light comes across as an unlikely love story. Both John Churchill and Sarah Jennings were incredibly ambitious people, and each of them was looking to make an advantageous marriage at the time they met and quite accidentally, fell in love. Churchill had risen from a mere page to become a favorite of the Duke of York, later James II. Sarah came from lower tier aristocracy, but became an intimate of Princess Anne. Although neither had the social status to be a likely candidate for marriage at the time they met, they simply found one another irresistible. Sarah’s parents had urged her to hold out for someone rich.

When Sarah was an equal partner, theirs was a winning team. John was the military strategist and statesman. Sarah was the politician and courtier, both at the Court of James II, and later, at the courts of William & Mary and later, Queen Anne.

It was during Queen Anne’s reign that Sarah Churchill became the power behind the throne. Unfortunately, she did not wield her power graciously. While her husband was in Europe waging war, his duchess was heavy-handed in her management of the Queen and at times was a notorious bully. Sarah was incredibly bright and spared no words in letting Anne know which of them was the superior intellect. She also was an avid Whig, who made every prominent Tory her personal enemy. As time went on, Sarah overplayed her hand with the queen and Marlborough paid the price. Queen Anne withdrew her support of Marlborough’s military efforts on the eve of a complete capitulation of the opposition, and Marlborough was recalled. His political enemies lodged trumped-up charges of embezzlement against him over a government contract for bread, what today would be called a kickback. Soon thereafter, The Queen was so embittered by Sarah’s insensitivity over the death of her son that she and her ministers reneged on their gift of funds to complete the Marlborough’s mammoth construction project near Woodstock, Blenheim Palace.

In the wake of a campaign to discredit the duke, the Marlboroughs withdrew not just from the court, but from the country. They lived in high style in the German principalities and the Netherlands, where the Duke’s military genius and statesmanship during the War of the Spanish Succession was a legend. Even the French king held him in high esteem.

When Queen Anne died childless and the crown passed to the House of Hanover, the Churchills were again in favor at home in England. King George and Marlborough had fought side by side and were good friends. Nevertheless, the Duke would probably have been happy staying away, but Sarah wanted to go home. However, even in an England ruled by the House of Hanover, Sarah’s strong will and irascible temper alienated Queen Caroline. They devoted most of their attention to managing their properties. When the Duke died, Sarah Jennings Churchill was one of Europe’s wealthiest women. She completed construction of Blenheim Castle after her husband’s death and made life close to unbearable for its architect.

Even in her advanced age, she was plagued by suitors young enough to be her son. She is said to have spurned one of them in the language quoted by Sir Winston Churchill in his famed biography[9]:

“If I were young and handsome as I was, instead of old and faded as I am, and you could lay the empire of the world at my feet, you should never share the heart and hand that once belonged to John, Duke of Marlborough."If that quotation does not provoke a tear, it is hard to imagine what would. Theirs was so torrid a love affair that the Duchess once remarked to a friend that when he came home from the wars, they made love before he took his high boots off.

While Sarah’s outspoken politics and rude treatment of the Queen prevented her husband from achieving total domination of Europe, he is widely credited for raising England from a minor to major power.[10] There is no doubt his success was aided by the support he received from Queen Anne at the insistence of his Duchess. In conclusion, there is more to the life and times of the Duke of Marlborough than politics and romance. While I was in college in the late 50’s, I discovered John and Sarah Churchill and fought the battle of Blenheim on my cot. For those who have the slightest interest in military history, it is worthy of a reenactment.

Thank you for joining me in a brief glimpse of three of history’s many great love stories. I predict there will be more to come.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Linda Root is the author of six historical novels set in the late 16th and early seventeenth century, The First Marie and the Queen of Scots, (2011) and The Last Knight and the Queen of Scots (2013), both large historicals, and the Legacy of the Queen of Scots Suite consisting of four books to date and the fifth coming in November. She also writes historical fantasy under the name J.D. Root. Root is a former major crimes prosecutor living in the high desert above Palm Springs with husband Chris and two Alaskan malamutes Maxx and Maya. Visit her Visit her author’s page.

Linda Root is the author of six historical novels set in the late 16th and early seventeenth century, The First Marie and the Queen of Scots, (2011) and The Last Knight and the Queen of Scots (2013), both large historicals, and the Legacy of the Queen of Scots Suite consisting of four books to date and the fifth coming in November. She also writes historical fantasy under the name J.D. Root. Root is a former major crimes prosecutor living in the high desert above Palm Springs with husband Chris and two Alaskan malamutes Maxx and Maya. Visit her Visit her author’s page.Artwork from Wikimedia Commons, original art by Linda Root.

[1] Goldsworthy, Adrian, Antony and Cleopatra, Yale University Press; 1St Edition edition (September 28, 2010)

[2] Shiff, Stacy, Cleopatra: A Life

[3] Daily Mail, Keiran Cochoran, September 25, 2015, Mailonline ‘Mary Queen of Scots is CLEARED of murdering her husband by a panel of experts who re-examined the evidence... just 428 years after she died.

Read more.

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter

DailyMail on Facebook

Read more.

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter

DailyMail on Facebook

[4] Wikipedia Commons, Ainslie Tavern Bond

[5] Guy, John, Queen of Scots, The True Life of Mary Stuart, pp 314-318.

[6] Wikipedia, op. cit.

[7] Guy, op cit.

[8] Antonia Fraser, Mary Queen of Scots,

[9] Marlborough: His Life and Times. By Winston S. Churchill. 4 vols. (London: George G. Harrap and Company, 1933-38).

[10] Politics and War in Churchill’s Life of the Duke of Marlborough by James W. Muller. The Imaginative Conservative

[10] Politics and War in Churchill’s Life of the Duke of Marlborough by James W. Muller. The Imaginative Conservative