Here's to a slice of Cake and a cup of mulled wine or Wassail in honor of Twelfth Night.

The origin of Twelfth Night is sometimes traced to the ancient Roman festival of Saturnalia because of the appearance in many of its versions of a mock king. Adaptations of Roman festivals in medieval European courts often featured the appearance of a false sovereign sometimes called the Lord of Misrule, but the title of the bogus monarch common to the Twelfth Night holiday on the eve of the Feast of Epiphany was most often known as the King of the Bean. The tradition was also adopted in Spain, the Low Countries and the German principalities, although in Germany and the Netherlands, the item in the winning slice was a coin. It has been speculated as inevitable that the French would combine their love of the culinary arts with their passion for spectacle, in a celebration conferring temporary kingship on a courtier who found a bean hidden in his marzipan or honey cake. The French phrase meaning, ‘he had good luck’ –il a trove lafeve au gateau—literally translated to ‘he found a bean in his cake.'

Twelfth Night entertainments at British Courts did not begin with Shakespeare

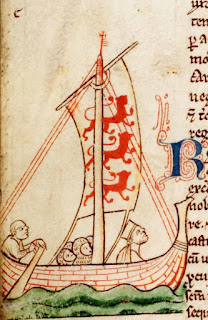

The comedic flavor attributed to the festival of Twelfth Night did not begin with the mishaps of William Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers, nor was it exclusively a British holiday. Shakespeare wrote his play at the turn of the 17th century, and it was first performed in 1602. The plot centers around fraternal twins who were separated in their youth by a shipwreck. One of them, Viola, resurfaces in adulthood as a trickster who often disguises herself as a man. She falls in love with Count Orsini, who is in love with Countess Olivia, who meets Viola while she is wearing her disguise and falls in love with her. The predictable series of misadventures follow.

The Masque of Blackness, script by Ben Johnson, Costumes and Set design by Inigo Jones, Starring Queen Anne of Denmark and sixteen ladies of the Court

|

| Blackness costume design by Inigo Jones |

At least one Twelfth Night celebration, this one at the Stuart Court in 1605, was controversial in its time and certainly would not pass political correctness tests of current times. The production was sponsored by Queen Anne of Denmark, the first English Stuart consort, and entitled The Masque of Blackness. The play was written by Ben Jonson, and the set designs and costumes and props were the work of Inigo Jones. Queen Anne was a great fan of masques and often performed in them. In Blackness, she played the part of Euphorus and appeared in black face. Even then, a theme centering on skin color was considered improprietous by some of the Queen’s critics. The plot involves a group of African women who had regarded themselves as the most beautiful women in the world until learning black skin was considered ugly outside of Africa. The story advances as the women explore the known world seeking a way to make themselves white. It ends with a promise that the next year’s masque will involve Beauty, in which the black-faced women are likely to discover themselves in Britannia, where pale skin was the norm. However, performance of the second installment of the story, entitled Beauty, was postponed to 1608, to permit the 1607 Twelfth Night reveries to focus on a Wedding Masque of Robert Devereaux, Earl of Essex and Lady Francis Howard, who proved to be a couple more mismatched than any pair either Shakespeare or Ben Jonson could have conjured.

Queen for a Day: Twelfth Night at the Court of the Queen of Scots

My favorite Twelfth Night story comes in two installments of a love story I uncovered when I researched my debut novel, The First Marie and the Queen of Scots, and it involves Twelfth Night reveries which occurred in Scotland during Marie Stuart’s brief personal rule. The story begins in France during Queen Marie Stuart's youth. At the mid-sixteenth century French court at which King Henry Valois’s elegant mistress Diane de Poitiers set the tone, it is not surprising to find the selection of a Queen of the Bean incorporated into the festivities. Traditionally, a white bean was placed into a honey cake in the royal kitchens and served to female members of the royal household, the first piece given to the oldest. Like most things associated with Diane, the tradition caught the fancy of Marie Stuart, Queen of Scots, when she was Dauphine, and later, Queen Consort, and she brought the tradition home with her to Scotland in 1561.

The version she introduced commemorated her own sovereignty by making the featured attraction the selection of a Queen of the Bean. No King of the Bean appears in the histories of her reign, which the consort Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, should have heeded. There is no record as to precisely when the Queen introduced the lottery of the honey cake, but there is some indication that Lady Marie Beaton may have been the winner in 1563. However, the Twelfth Night celebrations of 1564 have survived in some details and were vividly commemorated by descriptions reported to the Crowned Heads of Europe. It was the year when the bean was found in the honey cake of Marie Fleming, the Queen’s first cousin and leader of the Queen's ladies called The Four Maries. The petite blond woman who had been lauded by French poets as one of the most beautiful women in the world appeared dressed in a gown of silver and covered from head to toe in jewels. Even Beaton’s paramour, the English ambassador Thomas Randolph sent reports to Queen Elizabeth and to the Queen Mother Catherine d' Medici at the French Court comparing Fleming to three goddesses from classical mythology and describing her presence as eclipsing the Queen. Even stiff-necked George Buchanan praised her demeanor and her beauty. It is fitting to note that the last Twelfth Night celebration of Marie Stuart's six-year personal rule was held at Court in 1567, when the former Queen of the Bean, Marie Fleming, married the celebrated Scottish diplomat and foreign minister Sir William Maitland of Lethington who had fallen in love with her presumably at her appearance on Twelfth Night, 1564. Through their daughter, Margaret Maitland (Kerr), Lady Roxburghe, the bride and groom are remote ancestors of the late Diana, Princess of Wales, and hence, her sons, William, Duke of Cambridge and Prince Harry of Wales. The Twelfth Night Celebration of 1564 is commemorated annually in Biggar, Scotland, the Fleming ancestral home.

Twelfth Night in the New Millennium

The popularity of Twelfth Night festivities caught on in 18th century America and were very popular with George and Martha Washington, who chose it as the date of their wedding. Nevertheless, the nature of the holiday changed with time. By the 19th century, the tradition involving the election of a King or Queen for a Day had all but disappeared. Such, perhaps, is the fate of monarchy. However, its vestiges are seen in Provence and to some degree, in Germany. By the early 19th century, the festival had taken on a carnival mood and was a favorite holiday of the great Jane Austen. However, late in the 19th century, Queen Victoria outlawed its celebration as having become too raucous. Its popularity survived longer in the Americas, but by the 20th century, it had become an occasion for the taking down of decorations and the extinguishing of the Yule Log. In current times, especially in traditional households where Epiphany is celebrated, Twelfth Night is commemorated with cake and a punch bowl of wassail, which is happily consumed and put away until the next Christmas season. Thank you for celebrating it with me.

~~~~~~~~~~

Linda Root is a retired career prosecutor, armchair historian and historical novelist who lives in the Morongo Basin area of the California high desert within a quarter mile of the Joshua Tree National Park. Her books take place in Marie Stuart’s Scotland and Stuart England, and can be found at Amazon.com, Amazon.uk.com and Amazon Kindle. Her eight book and current work in progress, The Deliverance of the Lamb, will be published in the late Spring, 2018.