by Terry Kroenung

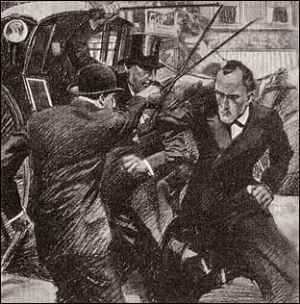

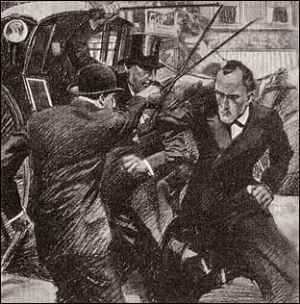

The usual homeless lads had returned to the Oxford Street alley. Paragon noted their drunken snores and detoured around them. Within four paces of exiting the dark, narrow passage what little light had been visible at its opening vanished. A wide-shouldered figure in an immense topper blocked his way. While his brain absorbed that, the supposedly-sleeping pair he had just passed scrambled to hobnailed feet. One glance over his shoulder revealed stout cudgels and handkerchiefs across their faces.

These were no beast-men. Merely hired London bully-boys. Still, Paragon did not quite manage to evade the blow aimed at his right ear. He pivoted left, but still caught it on the shoulder. His Malacca stick clattered to the ground as his arm went numb. On his left the other man swung his cudgel at his exposed temple.

Paragon stepped inside the arc of the arm and used his would-be slayer’s own impetus to fling him into his partner. With no feeling in his right arm yet, and his stick out of reach in any event, he had to rely on some particularly unsavoury Parisian street fighting.

Whenever traveling in dangerous areas Paragon liked to slip on his Apache ring. A complex steel Medusa’s head with a small grip that rested against his palm, he had removed it from a deceased French gangster in Montmartre who had endeavoured to garrote him. Before the attackers could recover from his counter-stroke, he snapped a coup de pied bas into the knee of one with his aluminum foot. The vicious low kick brought the wincing man’s face down to the perfect height for a powerful left cross to his jaw. Paragon’s dreadful ring left Medusa’s bloody portrait on the bloke’s face as it put him down and out.

His opposite number tried to sneak in a killing blow to the crown of the actor’s head, since the boater offered little protection. Sliding left, Paragon let the fellow’s cruel cudgel spend itself on empty air. With the rowdy’s balance upset the fellow could not evade a powerful aluminium side kick to his ribs. The hapless villain’s body smote the unforgiving wall with a wet smack. As the fellow bounced from it Paragon elbowed his throat and turned to engage the giant who blocked his escape.

Except that the third man had gone.

This excerpt from my pending Steampunk novel,

Paragon of the Eccentric, illustrates a few principles of the first true mixed martial art in the West since ancient Greek Pankration, the first to blend Asian and European techniques. Though the name Bartitsu can promote snickers and occasional calls of ‘Gesundheit!’ it is a deadly-serious means of self-defense and can claim a rich legacy in the annals of combat and literature (Arthur Conan Doyle had Sherlock Holmes employ it to defeat Professor Moriarty). Appearing, albeit in somewhat altered and anachronistic form, in such works as Will Thomas’ Barker/Llewelyn novels and the recent Sherlock Holmes films, Bartitsu is a wonderful means of spicing up your Steampunk or Victorian writing.

Bartitsu is a portmanteau word derived from a blending of the surname of its inventor, Edward Barton-Wright, and the Japanese discipline of ju-jitsu. Barton-Wright studied the latter when he was in the East working as an engineer in the 1890’s. He returned home to find the London papers full of outrage about a wave of street crime. Proper gentlemen and ladies were being regularly assaulted and robbed. To address this thuggish violence he developed a system of personal defense which he claimed could

“meet every kind of attack, armed or otherwise.”

His system blended techniques found in boxing, wrestling, French savate, la canne (walking stick), and ju-jitsu. Of these, the last named features most prominently in Barton-Wright’s description of Bartitsu’s guiding principles:

“1) to disturb the equilibrium of your assailant 2) to surprise him before he has time to regain his balance and use his strength 3) if necessary to subject the joints of any part of his body whether neck, shoulder, elbow, wrist, back, knee, ankle, etc. to strain which they are anatomically and mechanically unable to resist.”

Any modern student of aikido (my martial art of choice, also a child of ju-jitsu) will recognize these principles. The opponent’s own momentum and strength are redirected and used against him. This was no sport for effete British dilettantes. Indeed, there is no competitive form of Bartitsu at all. From the first it was intended to be a means of defense against ruthless alleyway assailants. Fast, violent, and effective, Barton-Wright’s system aimed to put an attacker down as soon as possible and render him incapable of further outrage (though he took pains to advise that it not be taken to extremes or be used to hurt a man who has been made helpless).

This system embraces every possible eventuality and your defence and counter-attack must be based entirely on the actions of your opponent. Even though Barton-Wright’s original Pearson’s articles mentioned some 300 reactions to common situations, he insisted that the essence of Bartitsu was the fluidity of mind and body to respond to the circumstances of the encounter.

It was expected that the middle-class patrons trained at his Soho Bartitsu Club would never initiate an attack, but only take action when threatened. To this end there are few purely offensive techniques described, though an unscrupulous practitioner could always adapt Barton-Wright’s principles to the wrong ends.

Bartitsu tends to be fast and fluid, offering the writer a great variety of exciting moves when used in an action scene. There is little toe-to-toe pounding involved. If a tactic fails or is blocked, the Bartitsu fighter immediately abandons it in favor of another.

Besides the five primary disciplines already mentioned, great store is set on the employment of clothing and found weapons. Barton-Wright mentioned bowlers, coats, umbrellas, hatpins, and even bicycles as equalizers in a fight. In my books I have included all of these and more. They make for dandy spectacles of mayhem. Here’s another one from

Paragon of the Eccentric as an illustration. (Note: Millie is a DNA experiment and has two tentacles at the base of her skull, one with teeth)

He gripped the fountain pen in his left hand, each rounded end protruding from his fist. “But we are not without resources.”

“What?” inquired Tilley. “You plan to write satirical poems at them?”

Pausing at the foot of the grimy steps, he jerked up the right leg of his trousers to expose his artificial calf. Out of its hidden compartment he took a six-inch black metal tube.

“Resources?” said Amber with a dubious note in her voice. “Some marvelous new death ray, perhaps?”

With a snap of his wrist the steel baton expanded like a telescope to its full eighteen inches. “Rather more primitive than that, but effective nonetheless. Apply it to any offered skulls, wrists, or knees.” He looked at Vesta. “Remember your training. Queue’s lessons shall serve you well. Millie, I do not have to tell you how to control a man, do I?”

The dollymop waved a dismissive hand. “It’s me stock in trade, ain’t it?”

Paragon burst up through the hatch and into the room before the nearest man could do much as raise his eyebrows. The heavy brass pen spiked him in the temple. He dropped as if shot point-blank.

Shouts. Blurred motion. Chaos. Curses and threats. Six other men reached for their pistols or truncheons. One gun clattered onto the floor at once when Amber’s baton broke its owner’s elbow. He shrieked and backed into Vesta, who seized his abused arm to whirl him into another bloke who had raised his billy to strike at Lady Moura from behind. Little Tilley, fully invested in her male persona, used her fists to jab the next chap in the nose and throat. A savate kick to his belly sent him down the hatch hors-de-combat. True to her promise, Millie simply reached down to take hold of her man’s bollocks as if crushing walnuts. When he raised a hand to bat her away a fanged tentacle bit into his palm and worried at it like a terrier with a rat.

Someone bear-hugged Paragon from behind to immobilize him so that another could apply a bludgeon from the front. A vicious stab of the pen into the hugger’s cheek made him loosen his hold, while a low kick from Paragon’s invincible right foot broke his partner’s knee. He turned, twisted the other’s arm like a corkscrew and spun him into a wall.

Pictures being worth much more than a thousand words, I encourage the reader to consult the Resources section of this article for photographic ad video illustrations of the essential Bartitsu techniques. That said, here are a few very basic descriptions of the basic disciplines.

Stick:

Barton-Wright naturally presumed that anyone in his audience would likely be in possession of a walking stick or umbrella when in the street. To that end Bartitsu relies quite a bit on stick play inherited from saber tactics and prior stick-fighting systems. Much of this came from his stick instructor at the Bartitsu Club (located in the appropriately-named Shaftesbury Avenue in Soho), French/Swiss military man and combat

expert Pierre Vigny.

The stick is held like a club, thumb wrapped around the fist, rather than like a sword with the thumb along the shaft. Preference is given to remaining out of distance of the opponent and striking his arm or head. Often this involves inviting a particular attack and then sliding or pivoting out of danger while simultaneously swinging the stick at a vulnerable spot.

Also favored is defending and attacking in a single move, such as blocking a club aimed at one’s head and continuing on to assail the foe’s own body. Closing the distance to get inside the arc of a punch or stick-swing is recommended. While wrapping and disabling the attacking arm, the handle of one’s stick may then be used against vulnerable areas. Alternatively, the shaft can leverage joints.

What is not advised is engaging in a pure fencing match with another stick or club. Of great utility is holding the stick in two hands like a rifle with bayonet, relying on thrusts with the point. Concentrating the force in such a tiny area is very effective. One should keep in mind that the stick, like the other disciplines, is not used alone, but in combination with kicks, punches, and throws.

French kick-boxing, derived from the tough waterfronts of Marseilles, gives Bartitsu a handful of useful tactics. Barton-Wright did not go into detail in print about the kicks used in Bartitsu, so some speculation is involved; however, he does specify three savate kicks. A coup de pied bas mentioned in the opening selection, is a low front kick to the knee or shin. This would most likely be used as a spoiling move against an advancing opponent, or as a setup/distraction in combination with a stick strike or punch. The chasse´ bas lateral: a low side kick, requires a bending of the rear leg and straightening the front one while turning the outside edge of its foot up. It is then thrust at the thigh, knee, or shin, the blow landing with the heel or outer part of the foot. From personal experience while sparring I can attest that it will absolutely stop an onrushing attacker in his tracks when used against his kneecap.

Finally, the chasse´ croise median aims for the foe’s solar plexus or stomach. Skipping the rear foot behind and past the front, the latter is then pistoned out at the enemy’s midline.

Savate:

Another use for the foot, though not borrowed from savate, is to maneuver behind one’s attacker and collapse his knee joint by simply stepping on it. Very little force is required and gentle pressure on collar or shoulder will drop the largest man.

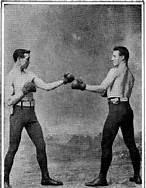

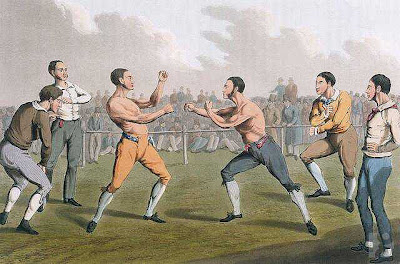

Boxing:

"In order to ensure as far as it was possible immunity against injury in cowardly attacks or quarrels, they must understand boxing in order to thoroughly appreciate the danger and rapidity of a well-directed blow, and the particular parts of the body which were scientifically attacked.” He also seemed to believe that every Englishman of any breeding would already know the basics of pugilism, because he said precious little about it other than to note that street fighting and Marquis of Queensberry boxing were very different and the latter had to be adapted to ensure success in a battle for survival against the expected unscrupulous opponent. In point of fact, much of what he said about it seemed to be aimed at knowing how to defeat the expected moves of a trained boxer.

Viewing film of boxing matches from 1894 (indeed, some of the oldest movies in existence), one sees that the style of Barton-Wright’s time called for a very upright stance with the arms extended. The thumb would be on top of the fist instead of wrapping it around for safety as we would now do it.

Whereas today we would keep the hands close to the face, hunkering behind them in a close guard, the realities of bare-knuckle boxing called for a different approach. The opponent was to be kept literally at arm’s-length, since his hands weren’t padded and could do significant damage.

The milling of one’s fists is no movie parody but was an actual technique of the age. It confused the foe and kept the hands primed for use, much like a volleyball player ‘dances’ the feet to be more ready for a quick reaction to the spike. Punches often tended to be almost lunges, the lead foot and fist moving together, though there was also plenty of swinging from the rear foot in the old films. Blocking with the arms more resembles defense in an Asian striking discipline than in modern boxing. The movements tend to be more exaggerated, not tiny and controlled.

Wrestling:

As with pugilism, the references to standard freestyle wrestling are not extensive, possibly for the same reason, that Barton-Wright expected all young men to have practiced the basics. But he also borrowed from Swiss schwingen, a grappling style inherited from medieval times that chiefly involved grasping the opponent at the hips and throwing him. Many of its techniques are nearly indistinguishable from judo moves, which themselves evolved from ju-jitsu in the 19th century. Since Bartitsu’s founder relied primarily on ju-jitsu for close-quarters work and ground fighting, he likely taught standard wrestling as much for knowing how to counter it as for using it in a fight.

Ju-jitsu:

Much enamored of this Japanese discipline, since he had studied it in its native land and was convinced of its efficacy, Barton-Wright wrote and spoke more about it than any of the other principle techniques. He clearly prized it, since he incorporated its final syllables into the name of his art. In fact, he went so far as to import three ju-jitsu masters when he returned home. Some of the attention he paid to it might be put down to its sheer novelty in Britain, as it required much more explanation. It was also what made Bartitsu so very different from other combative systems in the West.

It is the essence of ju-jitsu which informs Bartitsu’s core principles. It can be translated as “the art of yielding.” This is appropriate, since it teaches practitioners to use the enemy’s own momentum and strength against him. Developed by samurai to fall back upon when disarmed and fighting an armored foe, it replaced futile hand strikes with joint locks. As previously stated, it depends upon disturbing an assailant’s equilibrium, inviting hostile motion so as to make use of the foe’s own energy, and taking pre-emptive action with offensive defense.

This is the aspect of Bartitsu that gives it a grace and elegance while at the same time enabling its violent character when joined with the other disciplines. Stepping into an assault, blending with its direction and carving circles in space while rendering the opponent helpless looks almost dance-like when performed well. When employed along with punches, kicks, and stick-play, it makes for an exciting and unique fight scene readers will enjoy.

Clothing and Found Weapons:

Apart from walking stick display, this is the area of Bartitsu where the Steampunk author can add Victorian flair and color to her writing. Hats, overcoats, parasols, and pins are all mentioned by Barton-Wright as adjuncts to the Bartitsu practitioner’s standard arsenal. He recommended flinging a bowler into the opponent’s face as a distraction while closing to engage, or tossing a coat over his head. A sturdy hat could even serve as a buckler in the off-hand while striking with a stick. This is all absolutely efficacious, as I discovered in a full-speed Bartitsu free-play exercise. My student charged me with a stick with no choreography. Unarmed, I flung my hat into his eyes, pivoted, wrapped his stick arm with my left, and disarmed him with my right. Despite his knowing Bartitsu, he still lost to this move.

Barton-Wright was not remiss in advocating that ladies practice Bartitsu. Umbrellas, particularly those with crook handles, made fine weapons. Offending arms and legs could be hooked and the brolly’s tip into the throat would deter any ruffian.

A 14-inch hatpin to the eye would certainly end a fight in the lady’s favor. It is known that suffragettes such as Edith Garrud defended themselves against the police with ju-jitsu, though whether they actually trained at the Bartitsu Club itself is conjectural. Also an established fact is that the sister of Boy Scouts founder Lord Baden-Powell was an expert at defending herself with both parasol and walking stick.

Group Fighting:

Since it was well-established that the criminal element rarely offered a fair fight and commonly attacked in groups to ensure success, Bartitsu included tactics for engaging several assailants at once. Naturally Barton-Wright preached that one should not stand on ceremony or honor in such situations but rather flee with all haste. If one were to be trapped, however, he offered means to clear a path to safety. These depended on having a stick and employing it in wide sweeps and vigorous back-and-forth motions to

prevent surprise from the rear. Once room had been made, then the single man could proceed as the

situation dictated.

We will end with a final fight scene from

Paragon of the Eccentric:

She grasped a straight stick in her gloved hands and returned to the centre of the mat. Queue assumed the attitude of some ill-paid thug with minimal training as a fighter. Her stick sliced straight down at his skull while she bulled her way toward him.

Paragon pivoted on his front foot. Her impetus as the blow missed took her a step past him. Almost casually he stepped on her knee joint from the rear, causing her to fall onto that knee. A painless rap to the back of her shoulder with the light stick neck ended the first exchange.

Again they faced off. This time she swung her stick with both hands, as a frustrated rowdy might do. Like a batsman trying for six she chose a more horizontal path. Not so easy to avoid as a vertical attack.

Knowing this, Paragon did not attempt evasion. Instead he slid directly into her, body against body. Now the stick body was past him, unable to inflict harm. Adding his own force to hers, left arm across her stick arm, they spun like a top. He simply bent his knees as they went around, causing her to fall forward out of the spin. She landed on her back with a boom, his stick point against her throat.

After assisting her to rise, they met for a third time. Now she feinted another descending sabre cut, but as he raised his stick with both hands wide apart to parry it she shifted to a spiking bayonet-style strike at his chest. Leaving his stick up high, Paragon pivoted out of her stick’s path with a simultaneous left cross to her jaw. Despite her armour, the impact of the fist sent her sprawling.

Cursing under his breath, Paragon cast his stick aside and rushed to the immobile woman. He pulled off her bulky helmet to give her air. Queue’s eyes remained closed, her breathing shallow. “We need some help in here!” he bellowed, half-turned toward the door. “Halloo!”

The room swiveled as if on ball bearings. Before he could comprehend his predicament he lay flat on his back, staring into the painful glare of the electric ceiling lamps. A leg made of cast iron clamped onto each side of his arm, which was stretched high over his head. One heel bored into his throat. His air and voice were cut off. Jolts of pain shot along his arm as Queue hauled back on it, bending his elbow across her thigh. For good measure she ruthlessly twisted his wrist in a direction it had definitely not been designed to go.

I’ll be damned if I’ll tap out for her satisfaction.

Another three seconds showed him how much in error that last belief had been. Queue yanked on the arm as if trying to pull a locomotive down the track. At the same time her heel pressed in another two inches, until he positively gurgled and drooled.

Hopefully these few precepts concerning the Victorian/Edwardian fighting art will embolden you to craft exciting scenes of Steampunk or Victorian mayhem. While the normal tropes of the genre (those gears, clocks, and airships) are growing stale, Bartitsu is still fresh and unspoiled. Despite its century-old pedigree, book lovers are unfamiliar with it. Nothing thrills a reader quite so much as seeing a cool, well-dressed hero or heroine dispatching ill-mannered blokes. So let the sticks, feet, and erudite quips fly. Grace under pressure has always been the hallmark of good breeding and Bartitsu is certainly a means to that end.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Terry Kroenung is the author of the Legacy Stone series of American Civil War fantasy novels. Book One,

Brimstone and Lily, won the Bronze Medal in Fantasy/Science Fiction at the 2010 Independent Publishers Book Awards.

Jasper’s Foul Tongue followed the same year and the third volume,

Jasper’s Magick Corset will be out in November.

Paragon of the Eccentric, a Steampunk prequel to H.G. Wells’

War of the Worlds, is currently under consideration by Tor.

His story “Lonely Crutch” appeared in the anthology

Broken Links, Mended Lives, a Colorado Book Award finalist. “Winterlesson” where Santa Claus is shot down by the U.S. military (really), has been published multiple times, most recently by

Toasted Cheese literary magazine. “Bladelight” offers a distinctly different take on a rapier duel for love.

Originally a playwright, produced in New York City and Europe, his dramas include

Gentle Rain,

Coolness and Courage,

Blood and Beauty, and an adaptation of

The Three Musketeers that features a chorus line of dancing swordsmen and a henpecked Alexandre Dumas.

He teaches Writing, Literature, and Film at Niwot High School in Colorado and next year will add a course in Science Fiction & Fantasy. In his copious free time from teaching, writing, and performing Shakespeare he gives Bartitsu workshops at Steampunk conventions and writers’ gatherings.

RESOURCES

Barton-Wright, E.W.

The New Art of Self-Defence, Part 1: London, Pearson’s Magazine, March 1899.

Barton-Wright, E.W.

The New Art of Self-Defence, Part 2: London, Pearson’s Magazine, April 1899.

Barton-Wright, E.W.

Self-defence with a Walking Stick, Part 2: London, Pearson’s Magazine, January 1901.

Barton-Wright, E.W.

Self-defence with a Walking Stick, Part 2: London, Pearson’s Magazine, February 1901.

Cunningham, A.C.

The Cane as a Weapon: 1912

Gallowglass Academy Introductory Bartitsu: 2009

Lawson, Kirk:

Bartitsu: The Martial Art of Sherlock Holmes: 2006

Wolf, Tony

The Bartitsu Compendium, Volume 1, History and Canonical Syllabus: 2011

Wolf, Tony

The Bartitsu Compendium, Volume 2, Antagonistics: 2011

Wolf, Tony

Bartitsu: The Lost Martial Art of Sherlock Holmes: 2012

Wolf, Tony, et al International Bartitsu Society:

Academie Duello, Bartitsu Intro:

Bartitsu School of Arms:

Bartitsu Stick Sparring:

Then as now

circumstances and geography dictated risk. Jack the Ripper’s

outrages were committed in sordid Whitechapel, after all, and not in

genteel Kensington. A critical mass of the poor and desperate has

always led to increased criminality.

Then as now

circumstances and geography dictated risk. Jack the Ripper’s

outrages were committed in sordid Whitechapel, after all, and not in

genteel Kensington. A critical mass of the poor and desperate has

always led to increased criminality. "Physical

education is indispensable to every well-bred man and woman. A

gentleman should not only know how to fence, to box, to ride, to

shoot and to swim, but he should also know how to carry himself

gracefully, and how to dance, if he would enjoy life to the

uttermost. A graceful carriage can best be attained by the aid of a

drilling master, as dancing and boxing are taught. A man should be

able to defend himself from ruffians, if attacked, and also to defend

women from their insults."

"Physical

education is indispensable to every well-bred man and woman. A

gentleman should not only know how to fence, to box, to ride, to

shoot and to swim, but he should also know how to carry himself

gracefully, and how to dance, if he would enjoy life to the

uttermost. A graceful carriage can best be attained by the aid of a

drilling master, as dancing and boxing are taught. A man should be

able to defend himself from ruffians, if attacked, and also to defend

women from their insults."

,

,