by Charlene Newcomb

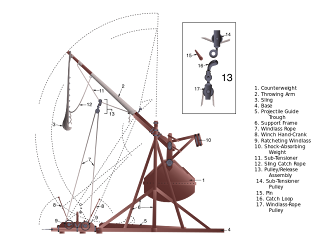

Surely one of the saddest, most horrible, and notorious events of the Third Crusade occurred on August 20, 1191. When Acre surrendered to Christian forces in July 1191 after a two-year siege, negotiators from within the city agreed to terms that included the return of Christian hostages and a fragment of the True Cross - captured by Saladin at the Battle of Hattin in 1187 - and payment to secure the release of Muslim hostages. Saladin was not involved in the negotiations, and contemporary accounts provide no evidence that the Muslin leader actually agreed to the conditions set on his behalf. There is no doubt Saladin knew the terms and used delay tactics whether to better position his troops or to stall the Christians' march to Jerusalem. In the words of chronicler Geoffrey de Vinsauf, Saladin “sent constant presents and messengers to King Richard to gain delay by artful and deceptive words.” The deadline was extended in hopes Saladin would come through.

What is clear: the terms of the surrender were not met. Twenty-seven hundred hostages were executed under orders issued by Richard the Lionheart.

Richard’s decision has been a cause for debate for centuries. In today’s world, this would be a war crime of huge magnitude. In 12th century warfare, the execution of hostages was not uncommon, though in many situations, hostages were kept under house arrest – sometimes for years – or sold as slaves.

Surely one of the saddest, most horrible, and notorious events of the Third Crusade occurred on August 20, 1191. When Acre surrendered to Christian forces in July 1191 after a two-year siege, negotiators from within the city agreed to terms that included the return of Christian hostages and a fragment of the True Cross - captured by Saladin at the Battle of Hattin in 1187 - and payment to secure the release of Muslim hostages. Saladin was not involved in the negotiations, and contemporary accounts provide no evidence that the Muslin leader actually agreed to the conditions set on his behalf. There is no doubt Saladin knew the terms and used delay tactics whether to better position his troops or to stall the Christians' march to Jerusalem. In the words of chronicler Geoffrey de Vinsauf, Saladin “sent constant presents and messengers to King Richard to gain delay by artful and deceptive words.” The deadline was extended in hopes Saladin would come through.

What is clear: the terms of the surrender were not met. Twenty-seven hundred hostages were executed under orders issued by Richard the Lionheart.

Richard’s dilemma: where do you house 2,700 hostages? How do you keep them fed when you must feed your own army? How many guards would it take to ensure the captives would not escape? With the departure of King Philip of France, Duke Leopold of Austria, and many of their supporters that summer, Richard needed nearly every able-bodied soldier on the coming pilgrimage to secure Jerusalem.

Why didn’t Richard sell his hostages? That would take time. It was already mid-August. The army needed to begin the march to Jerusalem or else run the risk of being caught by winter storms.

Based on morals and the conduct of war in the 12th century, are these excuses or valid reasons to execute close to 3,000 prisoners?

I was surprised that contemporary observers had very little to say about the executions. It is incredible to read the accounts of wholesale slaughter generally described in such nonchalant terms.

Roger de Hoveden writes:

On the seventeenth day of the month of August, being the third day of the week and the thirteenth day before the calends of September, the king of England caused all the pagans who belonged to him from the capture of Acre to be led out before the army of Saladin, and their heads to be struck off in the presence of all . . .

De Hoveden does provide more detail than most chroniclers and further along that passage he describes what the Christians did to the bodies. It is horrific, and I won't repeat it here. He then continues:

On the twenty-first day of the month of August, after the slaughter of the pagans, the king of England delivered into the charge of Bertram de Verdun the city of Acre. . . On the twenty-second day . . . the king of England crossed the river of Acre with his army, and pitching his tents between that river and the sea, on the sea-shore between Acre and Cayphas, remained there four days.

On the twenty-first day of the month of August, after the slaughter of the pagans, the king of England delivered into the charge of Bertram de Verdun the city of Acre. . . On the twenty-second day . . . the king of England crossed the river of Acre with his army, and pitching his tents between that river and the sea, on the sea-shore between Acre and Cayphas, remained there four days.The chronicler Geoffrey de Vinsauf writes:

. . . 2700 of the Turkish hostages [were] led forth from the city and hanged ; [King Richard's] soldiers marched forward with delight to fulfill his commands, and to retaliate, with the assent of the Divine Grace, by taking revenge upon those who had destroyed so many of the Christians with missiles and arbalests.Ambroise writes:

Two thousand seven hundred, allEven Muslim contemporary writers have not provided us more than a few sentences about the event. Ibn al-Athir writes that Saladin and his emirs did not trust the Franks (the term used to denote the European Christians). Al-Athir felt that the crusaders intended 'treachery' and would not free the hostages even if Saladin met the demands. Al-Athir then notes:

In chains, were led outside the wall,

Where they were slaughtered every one;

And thus on them was vengeance done.

For blows and bolts of arbalest.

On Tuesday 27 Rajab [20 August 1191] the Franks mounted up and came outside the city with horse and foot. The Muslims rode out to meet them, charged them and drove them from their position. Most of the Muslims they had been holding were found slain. They had put them to the sword and massacred them but preserved the emirs and captains and those with money. All the others, the general multitude, the rank and file and those with no money they slew.The chronicler Baha' Al-Din writes:

Then they brought the Muslim prisoners whose martyrdom God had ordained, more than three thousand men in chains. They fell on them as one man and slaughtered them in cold blood, with sword and lance . . .He is one of few contemporaries who comments on Richard's motives:

Many reasons were given to explain the slaughter. One was that they had killed as reprisal for their own prisoners killed before then by the Muslims. Another was that the King of England had decided to march on Ascalon and take it, and he did not want to leave behind him in the city a large number (of enemy soldiers). God knows best.Richard justified his actions in a letter to the abbot of Clairvaux. This was war, and Saladin had not met his end of the agreement. Many of Richard's contemporaries and numerous scholars over the years have condemned the Lionheart for his decision. It was a brutal and unchivalrous act. Would Richard's reputation have suffered less if the besieged had chosen to fight to the bitter end? Those sieges did not end well for the losers: pillaging, burning, and killing. But the garrison at Acre had surrendered. Richard sought advice from his council, and seeing no alternatives if he intended to be at Jerusalem's gate before winter set in, he issued the orders.

Sources

Ambroise. The history of the holy war : Ambroise’s estoire de la guerre sainte. (Trans. by Ailes, M., & Barber, M.) Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2003.

De Hoveden, R. (1853). The annals of Roger de Hoveden, comprising the history of England and of other countries of Europe from A. D. 732 to A. D. 1201. (Henry T. Riley, Trans.). London: H. G. Bohn. (Original work published 1201?)

"Geoffrey de Vinsauf's itinerary of Richard I and Others, to the Holy Land" in Chronicles of the Crusades: contemporary narratives, compiled and edited by Henry G. Bohm. London: Kegan Paul, 2004.

Gillingham, J. (1978). Richard the Lionheart. New York: Times Books.

Ibn al-Athīr, ʻIzz al-Din. (2007). The chronicle of ibn al-athīr for the crusading period from al-kāmil fi’l-ta’rīkh. (Trans by Richards, D. S.) Aldershot ; Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Ibn Shaddād, Bahāʼ al-Dīn. (2001) . The rare and excellent history of Saladin, or, al-Nawādir al-Sultaniyya wa’l-Mahasin al-Yusufiyya. (Trans by Richards, D. S.) Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate.

Siege of Acre By Blofeld of SPECTRE at en.wikipedia (Transfered from en.wikipedia) [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ASiege_of_Acre.jpg

Richard the Lionheart Merry-Joseph Blondel [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ARichard_coeur_de_lion.jpg

"SaracensBeheaded" by Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville - François Guizot (1787-1874), The History of France from the Earliest Times to the Year 1789, London : S. Low, Marston, Searle &

Rivington, 1883, p. 447. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SaracensBeheaded.jpg#/media/File:SaracensBeheaded.jpg

This post was originally posted on English Historical Fiction Authors on Wednesday, August 19, 2015.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Charlene Newcomb is the author of Men of the Cross and For King and Country, two historical adventures set during the reign of King Richard I, the Lionheart. For King and Country is an HNS Editors Choice, long listed for the 2017 HNS Indie Award. Men of the Cross was selected as an indieBRAG Medallion honoree in 2014..

Charlene is a member of the Historical Novel Society and a contributor and blog editor for English Historical Fiction Authors. She lives, works, and writes in Kansas. She is an academic librarian by trade, a former U.S. Navy veteran, and has three grown children.

Connect with Char: Website | Facebook | Twitter | Amazon