by Anna Belfrage

In March of 1330, a parliament was held at Winchester. As always since 1327, the young king Edward III officially presided, but the real power lay with his regents: his mother, Queen Isabella, and her favourite & purported lover, Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March.

The men assembling in Winchester fell into two categories: those who supported the regents and those who didn’t. The king himself belonged among the latter, but as things stood, our seventeen-year-old king had no option but to smoulder and bear it—for now.

Among Mortimer’s more vociferous enemies were Henry of Lancaster, cousin to the king, and Edmund of Woodstock, Earl of Kent and the king’s uncle. When the Winchester parliament opened, Edmund was not among those present. He was under arrest—for treason.

|

| Edmund's coat of arms |

Let us take a few steps back: Edmund of Woodstock was born in 1301, the second son in Edward I’s second marriage. As can be deduced from his name, he was born at the palace of Woodstock, and we can assume there was quite some rejoicing at his birth—Edward I now had three sons to safeguard his bloodline.

When Edward I died in 1307, Edmund’s half-brother, Edward II, became king. The age-gap between the new king and his much younger brothers was such that we can assume their relationship was somewhat distant—Edward was busy governing his kingdom and enjoying the freedom his new role brought with it and likely had little time for Edmund and his brother Thomas of Brotherton.

Edward I had made plans for his two younger sons, but had not followed through on them prior to dying. His intention had been to settle an earldom each on his sons, but early on in his reign Edward II decided to invest his beloved favourite Piers Gaveston with the earldom of Cornwall, which was one of the titles earmarked for his brothers. Edmund’s mother seethed, Edward likely shrugged—but as his brothers grew older he invested Thomas as Earl of Norfolk and granted Edmund sufficient land to keep the lad in style.

|

| Edward II dining in splendid isolation |

Where Thomas of Brotherton rarely emerges from the shadows in what documents we have, Edmund has left a substantial impression. He quickly proved himself a capable servant of his king, especially during those tumultuous years when Roger Mortimer and Thomas of Lancaster led the baronial revolt against Edward II in 1321-22. Edmund was in the thick of things—all the way from the initial conflict at Leeds Castle to the signing of the execution order for the captured Thomas of Lancaster.

The baronial rebellion was quashed, Mortimer was thrown in the Tower, and Edward was very pleased with his young brother, who emerged from the fray as the Earl of Kent and holder of substantial lands in the Welsh Marches. Our Edmund had every reason to be grateful to his royal brother—except, of course, that where Edmund got some land, Edward’s new favourite, Hugh Despenser, got much, much more land. In fact, so generous was the king to Hugh that he had an annual income almost four times higher than Edmund’s. Not something that pleased Edmund—or anyone else, to be honest, seeing as the English barons were getting very tired of the grasping Despenser.

In the aftermath of the baronial rebellion, Edward II, together with his trusted advisors Bishop Stapledon and Hugh Despenser, implemented what is best described as a dictatorship. Anyone suspected of colluding with the rebels risked losing everything they had, including their lives. Their paranoia increased tenfold when Mortimer managed to escape from the Tower and flee to France. Suddenly, the baronial opposition had a leader again, and the more heavy-handed Edward II and Despenser became, the more attractive the option of joining Mortimer became.

Not only did Edward manage to aggravate his barons. He also alienated his wife when he deprived Queen Isabella of her dower lands. Isabella was closer in age to Edmund than to her husband, and seeing as she was drop-dead gorgeous and Edmund was just as mouth-wateringly handsome, I imagine these two shared a common admiration for each other. Besides, they were cousins, grandchildren to Philip III of France.

At the time, being French to any degree was not an advantage in England: yet again, England and France were at war, this time over Gascony. In 1324, Edmund was sent to France to attempt a diplomatic solution, and when that failed he was put in charge of defending Gascony, an almost impossible task seeing as Edmund lacked both men and means. But he did his best, holding out until late September of 1324 before he was forced to surrender and agree to a six-month truce.

Edmund chose to remain in France. Maybe he preferred not to face his brother’s wrath at having failed him in Gascony, or maybe he was sick and tired of dancing attendance of the royal chancellor, Hugh Despenser. Whatever the case, he was in France when Isabella arrived in March of 1325, charged by her husband with the delicate task of negotiating a permanent truce between him and his French counterpart, Charles IV.

How Isabella had managed to convince Edward to entrust her with this mission is unknown, but I suppose Isabella was smart enough to hide her anger and humiliation at being deprived of all her income while promising herself she would have revenge—some day. Whatever her feelings, she successfully negotiated a treaty with her brother Charles. All Edward II had to do was to come to France and do homage for his French lands and everything would be peachy-pie.

|

| Edward of Windsor doing homage to Charles IV with his mama at his side |

Except that Edward II didn’t want to come to France—or rather, Hugh Despenser didn’t want him to go, worried that the moment the king left the country, the baronage would rise in rebellion and kill poor Hugh. Probably a correct assessment of the sentiments of the time, and apparently Edward agreed. Instead of going himself, he sent his young son and heir, Edward of Windsor. Unwittingly, he had thereby handed Isabella the weapon with which to destroy him.

Young Edward came to France, young Edward did homage, young Edward did not go straight back home as instructed by his father. Instead, he stayed with his mother, who simply could not bear to let him go. Isabella had collected several disgruntled English noblemen as her admirers, including Edmund of Woodstock. I imagine there were already whispers of invasions, of doing something to oust that despicable Despenser. When Roger Mortimer rode in to present himself to Isabella, the invasion had found its leaders: the extremely capable and ruthless combo of Isabella and Mortimer.

Edmund would likely not have been entirely thrilled at seeing Mortimer rise so rapidly in Isabella’s favour. Mortimer would not have been delighted at coming face to face with the man who’d been rewarded with Mortimer land for his efforts in putting down the rebellion of 1321. For the moment, whatever differences they had were laid aside, and to reinforce this fragile truce Edmund married Margaret Wake, Mortimer’s first cousin. By doing so, he sent a clear signal to his half-brother that he’d changed his allegiance, and in March of 1326 Edward II retaliated by stripping Edmund of all his lands and titles. (As an aside, Edmund and Margaret were to have four children, one of whom is Joan of Kent, famous for her beauty and her somewhat complicated marital life)

|

| Isabella leading the siege at Bristol |

Mortimer’s and Isabella’s invasion of England was a resounding success. Soon enough, Hugh Despenser was dead and Edward II was locked up in Kenilworth, his son crowned as Edward III in his stead. Edmund expected to be part of the inner circle that guided his young nephew, but neither Isabella nor Mortimer were all that interested in sharing their power. This did not go down well with Edmund, who was also struggling with feelings of guilt related to his deposed brother. That guilt became a crushing burden when it was announced in 1327 that their former king, Edward of Caernarvon, had died while in captivity.

In 1328, Edmund joined Henry of Lancaster’s rebellion against the regents, demanding that Mortimer be set aside in favour of the true peers of the realm. Mortimer acted with speed and determination. Edmund, knowing just how efficient Mortimer could be, abandoned Lancaster’s cause and returned to the royal fold just before Lancaster’s final humiliation.

By now, Edmund had acquired the reputation of being a weather-vane: first he’d supported his royal brother, then he’d joined Mortimer and Isabella, then he’d thrown his lot in with Lancaster only to change his colours yet again when things got sticky. Not a man to count on, one could say, even if Edmund would probably have disagreed, protesting that he’d been driven into rebellion against his brother and king by the grasping and conniving Despenser.

Whatever his reputation, Edmund was concerned with other matters: there were rumours that his brother had not died but was still alive behind the thick walls of Corfe Castle. Disenchanted with Isabella’s and Mortimer’s continued rule, Edmund chose to investigate further. One little piece here, another there, and soon enough Edmund was convinced his brother was alive. If so, what better way to right the wrongs he’d done his brother than to spring him from his prison and help him retake his throne?

This was the plot Mortimer uncovered early in 1330, his agents presenting him with a letter Edmund’s wife had written on his behalf to the imprisoned king. (In itself interesting: does this mean Edmund did not know how to write or was it a matter of penmanship?) Being somewhat gullible, Edmund had handed the sealed missive to an intermediary who’d promised to smuggle it into Corfe and hand it to the unhappy erstwhile king. Instead, the rascal gave it to Mortimer, and so Edmund was arrested and brought before parliament where his confession was read out loud.

There was only one verdict: death.

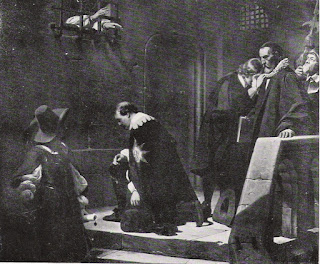

Appalled, Edmund threw himself on his nephew’s mercy, begging piteously for his life. He’d do anything—anything!—to prove his loyalty. He’d even walk all the way to London with a noose round his neck to atone for his actions. But there was nothing Edward III could do. Mortimer had seen to that, making it impossible for Edward to pardon his uncle without implicitly admitting there could be some truth in Edmund’s assertions that the former king was alive.

Whether or not Edward II was alive is, as per some historians, an open question. The men named as co-conspirators included several barons and bishops, men who would be in a position to know—and surely they’d not risk Mortimer’s displeasure for a dead man? We will never know, of course. It does, however, seem probable that Mortimer very much on purpose fed Edmund the little bits and pieces that convinced him his brother was alive, thereby luring the earl into treason. Ultimately, Mortimer’s behaviour in this matter would lead to his own death: the king, disgusted at having been duped into signing away his uncle’s life did not forgive. Or forget.

On a cold March morning in 1330, Edmund of Woodstock was led out to meet his maker. The executioner had done a runner, refusing to soil his hands with the blood of a man condemned for trying to help his brother. None of the assembled men-at-arms volunteered in his stead, neither did their captains. Poor Edmund shivered in only his shirt as the hours passed and no one was found willing to strike off his head. At long last, a condemned man undertook the task in exchange for a reprieve. The earl knelt. The axe fell. The severed head was held aloft, accompanied by the traditional cry of “

behold the death of a traitor.” Usually, the crowd would cheer. This time, no one did.

All pictures in public domain and/or licensed under Wikimedia Creative Commons

~~~~~~~~~~~

Had

Anna Belfrage been allowed to choose, she’d have become a professional time-traveller. As such a profession does not exist, she became a financial professional with two absorbing interests, namely history and writing.

Presently, Anna is hard at work with

The King’s Greatest Enemy, a series set in the 1320s featuring Adam de Guirande, his wife Kit, and their adventures and misfortunes in connection with Roger Mortimer’s rise to power. And yes, Edmund of Woodstock appears quite frequently. The first book,

In The Shadow of the Storm was published in 2015, the second,

Days of Sun and Glory, was published in July 2016, and the third,

Under the Approaching Dark, was published in April 2017.

When Anna is not stuck in the 14th century, she's probably visiting in the 17th century, specifically with Alex(andra) and Matthew Graham, the protagonists of the acclaimed

The Graham Saga. This is the story of two people who should never have met – not when she was born three centuries after him.

More about Anna on her website or on her blog!

David Mullaly’s first book is Eadric And The Wolves: A Novel Of The Danish Conquest of English. He bought and sold Viking artifacts for a dozen years, and he lives in Annapolis, Maryland. However, he remains desperately in love with English history, and is fascinated by what we know and what we don’t know about the Viking Age, especially in England and Ireland.

David Mullaly’s first book is Eadric And The Wolves: A Novel Of The Danish Conquest of English. He bought and sold Viking artifacts for a dozen years, and he lives in Annapolis, Maryland. However, he remains desperately in love with English history, and is fascinated by what we know and what we don’t know about the Viking Age, especially in England and Ireland.