By Lauren Gilbert

|

| Charles Elme' Francatelli, drawn by Auguste Hervieu, and engraved by Samuel Freeman about 1846 |

I have been enjoying the series Victoria on PBS. (It was so exciting that series 3 premiered in the U.S. BEFORE showing in the UK!) One character I particularly like is Mr. Francatelli, the chef in the palace. While it is true that Queen Victoria’s household did include a cook named Francatelli, there is a big difference between the way he is depicted in the television series and the known facts about him.

Charles Elme’ Francatelli is believed to have been born in London in 1805, to Nicholas and Sarah Francatelli. He actually grew up in France. He studied cooking at the Parisian College of Cooking, from which he received a diploma. He had the good fortune to study under the renowned chef Marie Antoine Careme (1784-1833), who served as chef de cuisine for the British Prince Regent (the future George IV) and was invited to Russia (although he left before cooking for the czar). When Francatelli returned to England, he cooked for various aristocratic households, until in late 1838 or early 1839, he went to work at Crockford’s. Crockford’s was a gaming establishment opened in 1828 by William Crockford in St. James’s Street. Crockford’s was known for its luxury and attention to detail, including a wide variety of games of chance and excellent food. Crockford’s was a fashionable and popular club, with a large and aristocratic membership. When the principal chef, Louis Eustache Ude, embroiled in a wage dispute, left (or was fired) in September 1838, Francatelli was selected to replace him and was known to be cooking there in February 1839. This brought him to the notice of a variety of noblemen, including William George Hay, the 18th Earl of Erroll.

In November 1839, the Earl of Erroll became Lord Steward of the Queen’s Household (Victoria was crowned in 1838). The chief cook at Buckingham Palace left on March 8, 1840. On March 9, 1840, at the recommendation of the Earl of Erroll (who apparently thought highly of Francatelli’s cooking), Mr. Francatelli became the chief chef’s replacement. During his tenure in the palace kitchens, Francatelli apparently exhibited a certain amount of artistic temperament (or just temper) and his kitchen staff functioned in a turbulent state. Late in 1841, Francatelli engaged in a dispute with Mr. Norton, at that time Chief Comptroller of the Household. He was suspended, and in December 1841, a quarter’s notice was given (whether by him or to him by the palace is unclear). At any rate, he left the queen’s employ on March 31, 1842. He returned to Crockford’s, where his cuisine was much appreciated, and he stayed there until the club closed January 1, 1846. (Due to a change of administration, the Earl of Erroll was no longer the Lord Steward as of August 30, 1841, so did not participate in the dispute.)

Francatelli’s first cook book THE MODERN COOK A Practical Guide for the Culinary Art in All Its Branches was published in early 1846. He dedicated the book to the Earl of Erroll on February 21, 1846 and thanked the earl for the opportunity to work in the palace. The cookbook became quite popular and went into multiple editions. This cookbook was geared toward the upper classes, and contained multiple bills of fare for each month of the rear, for diners in number from 6 to 300 depending on the season and the occasion. (The 28th edition in 1886 included a bill of fare for a dinner for Queen Victoria.) Later in the year, on June 1, 1846, Francatelli went to work for the Coventry House and remained there until it closed March 1, 1854. While so employed, in 1852, the first edition of his second book A PLAIN COOKERY BOOK FOR THE WORKING CLASSES was published. This differed greatly from his first effort, as it was geared for working-class families, and included a list of basic equipment needed, matters of cleanliness and economy, and a view to nourishing food.

Sometime in late June or early July 1854, Mr. Francatelli became the cook at the Reform Club, where he remained for some years. In 1861, his third cookbook THE COOK’S GUIDE AND BUTLER’S ASSISTANT: A Practical Treatise on English and Foreign Cookery and All Its Branches was published. In this book, recipe # 319 is Marrow Toast a la Victoria, which is seasoned bone marrow on dry toast; Francatelli indicated that Victoria ate this every day at dinner. This statement was supported by HER LITTLE MAJESTY The Life of Queen Victoria by Carolly Erickson; by the 1880’s, Her Majesty was eating Francatelli’s Marrow Toast with every meal for the sake of her digestion (apparently ruined by years of gobbling excessive amounts of food). In 1862, THE ROYAL ENGLISH AND FOREIGN CONFECTIONER: A Practical Treatise on the Art of Confectionary in All Its Branches was published, being his fourth cookbook. He left the Reform Club (or was let go) either late in 1862 or in January of 1863.

The St. James’s Hotel Company was formed in February 1863, with Mr. Francatelli listed as manager. The hotel opened May 2, 1863, and was managed by Mr. Francatelli and his wife. Later in that month, Francatelli also began cooking in the Prince of Wales’ household at Marlborough House (which was not far from the hotel), although he was not listed as an employee. This began another period of royal service. In addition to managing the hotel and cooking at Marlborough House, he also cooked for special occasions at Sandringham. He apparently stopped cooking for the Prince and Princess of Wales in the late summer or autumn of 1866, and focused on the management and cuisine at the St. James’s Hotel thereafter. He catered regimental dinners, and had special dinners featuring particular ingredients (such as horse meat, and Liebig’s Extract of Meat (a concentrated beef extract)), and a parliamentary dinner. He resigned as manager of the hotel in March 1870.

In October 1870, he was hired as the manager of the Freemason’s Tavern, which was his last place of employment. He functioned as the sole manager and catered special dinners. He retired in June 1876, and died on August 10, 1876 in Eastbourne.

As we can plainly see, his career differed significantly from the way the writers depicted it in the series Victoria. His actual royal service comprised barely 2 years for Queen Victoria, and about 3 ½ years for the Prince and Princes of Wales over 20 years after leaving Buckingham Palace. As an entrepreneur, he parlayed his relationship with royalty, particularly Queen Victoria, into cookbook sales. What about his personal life? That was different, as well.

Far from falling in love with and marrying Mrs. Skerrett, the Queen’s Dresser (and there really was a Mrs. Marianne Skerrett who was the Queen’s Dresser), Mr. Francatelli was in fact married well before he went to work at Buckingham Palace to Elizabeth Roberts, the wife who assisted him in managing the St. James’s Hotel until her death March 2, 1869. Apparently, Mr. and Mrs. Francatelli had a daughter Emily and a son Ernest. Mr. Francatelli remarried the next year. He and Elizabeth Cooke were married August 2, 1870, and he evidently had children with her as well, including a son Charles Elme’ Francatelli born in 1875. There is no indication of any opportunity (or inclination) for a palace romance between Mr. Francatelli and any woman employed in Queen Victoria’s household. Again, his personal life was quite different from that depicted on the television series. This does not make the series any less enjoyable; however, it does illustrate the need to watch with caution, as the engaging romance shown does not always reflect what really happened.

Sources include:

Chancellor, E. Beresford. LIFE IN REGENCY AND EARLY VICTORIAN TIMES An Account of the Days of Brummell and D’Orsay 1800-1850. London: B. T. Batsford, Ltd., 1926.

Chancellor, E. Beresford. MEMORIALS OF ST. JAMES’S STREET and CHRONICLES OF ALMACK’S. New York: Brentano’s, 1922.

Erickson, Carolly. HER LITTLE MAJESTY The Life of Queen Victoria. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997. P. 237

Francatelli, Charles Elme’. A PLAIN COOKERY BOOK FOR THE WORKING CLASSES. Oxford: Benediction Classics, 2012.

Stephen, Sir Leslie, ed. DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY, 1921-1922. Vol. 7. London: Oxford University Press.

Colin Smythe Ltd. “Charles Elme’ Francatelli, Crockford’s, and the Royal Connection.” Copyright (c) 2014-2015 Colin Smythe. HERE

Find-a-Grave Memorial. “Charles Elme’ Francatelli.” HERE

Researching Food History-Cooking and Dining. “Queen Victoria’s chef Charles Elme Francatelli” Copyright © 2017 Patricia Bixler Reber (posted February 6, 2017). HERE

Crockford’s 1828: HERE

Charles Elme’ Francatelli is believed to have been born in London in 1805, to Nicholas and Sarah Francatelli. He actually grew up in France. He studied cooking at the Parisian College of Cooking, from which he received a diploma. He had the good fortune to study under the renowned chef Marie Antoine Careme (1784-1833), who served as chef de cuisine for the British Prince Regent (the future George IV) and was invited to Russia (although he left before cooking for the czar). When Francatelli returned to England, he cooked for various aristocratic households, until in late 1838 or early 1839, he went to work at Crockford’s. Crockford’s was a gaming establishment opened in 1828 by William Crockford in St. James’s Street. Crockford’s was known for its luxury and attention to detail, including a wide variety of games of chance and excellent food. Crockford’s was a fashionable and popular club, with a large and aristocratic membership. When the principal chef, Louis Eustache Ude, embroiled in a wage dispute, left (or was fired) in September 1838, Francatelli was selected to replace him and was known to be cooking there in February 1839. This brought him to the notice of a variety of noblemen, including William George Hay, the 18th Earl of Erroll.

%2C_p283.jpg/800px-Crockford's_Club_House%2C_St_James's_Street_-_Shepherd%2C_Metropolitan_Improvements_(1828)%2C_p283.jpg) |

| Crockford's Club House, St. James's Street, 1828 |

In November 1839, the Earl of Erroll became Lord Steward of the Queen’s Household (Victoria was crowned in 1838). The chief cook at Buckingham Palace left on March 8, 1840. On March 9, 1840, at the recommendation of the Earl of Erroll (who apparently thought highly of Francatelli’s cooking), Mr. Francatelli became the chief chef’s replacement. During his tenure in the palace kitchens, Francatelli apparently exhibited a certain amount of artistic temperament (or just temper) and his kitchen staff functioned in a turbulent state. Late in 1841, Francatelli engaged in a dispute with Mr. Norton, at that time Chief Comptroller of the Household. He was suspended, and in December 1841, a quarter’s notice was given (whether by him or to him by the palace is unclear). At any rate, he left the queen’s employ on March 31, 1842. He returned to Crockford’s, where his cuisine was much appreciated, and he stayed there until the club closed January 1, 1846. (Due to a change of administration, the Earl of Erroll was no longer the Lord Steward as of August 30, 1841, so did not participate in the dispute.)

|

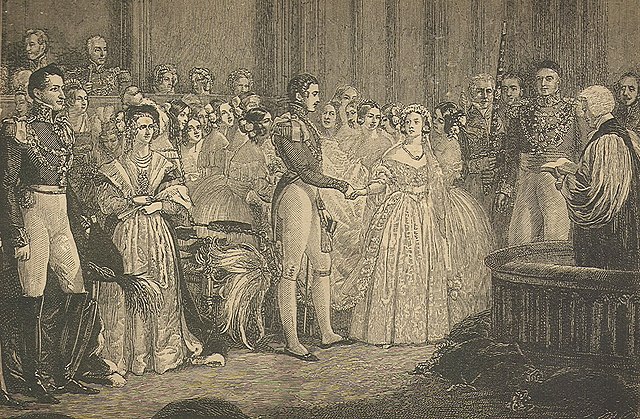

| The Young Queen Victoria, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1842 |

Francatelli’s first cook book THE MODERN COOK A Practical Guide for the Culinary Art in All Its Branches was published in early 1846. He dedicated the book to the Earl of Erroll on February 21, 1846 and thanked the earl for the opportunity to work in the palace. The cookbook became quite popular and went into multiple editions. This cookbook was geared toward the upper classes, and contained multiple bills of fare for each month of the rear, for diners in number from 6 to 300 depending on the season and the occasion. (The 28th edition in 1886 included a bill of fare for a dinner for Queen Victoria.) Later in the year, on June 1, 1846, Francatelli went to work for the Coventry House and remained there until it closed March 1, 1854. While so employed, in 1852, the first edition of his second book A PLAIN COOKERY BOOK FOR THE WORKING CLASSES was published. This differed greatly from his first effort, as it was geared for working-class families, and included a list of basic equipment needed, matters of cleanliness and economy, and a view to nourishing food.

|

| A Bill of Fare for Her Majesty's Dinner from THE MODERN COOK, 1886 |

Sometime in late June or early July 1854, Mr. Francatelli became the cook at the Reform Club, where he remained for some years. In 1861, his third cookbook THE COOK’S GUIDE AND BUTLER’S ASSISTANT: A Practical Treatise on English and Foreign Cookery and All Its Branches was published. In this book, recipe # 319 is Marrow Toast a la Victoria, which is seasoned bone marrow on dry toast; Francatelli indicated that Victoria ate this every day at dinner. This statement was supported by HER LITTLE MAJESTY The Life of Queen Victoria by Carolly Erickson; by the 1880’s, Her Majesty was eating Francatelli’s Marrow Toast with every meal for the sake of her digestion (apparently ruined by years of gobbling excessive amounts of food). In 1862, THE ROYAL ENGLISH AND FOREIGN CONFECTIONER: A Practical Treatise on the Art of Confectionary in All Its Branches was published, being his fourth cookbook. He left the Reform Club (or was let go) either late in 1862 or in January of 1863.

%2C_1846.png) |

| Receipt for Russian Salad from THE MODERN COOK 1846 |

The St. James’s Hotel Company was formed in February 1863, with Mr. Francatelli listed as manager. The hotel opened May 2, 1863, and was managed by Mr. Francatelli and his wife. Later in that month, Francatelli also began cooking in the Prince of Wales’ household at Marlborough House (which was not far from the hotel), although he was not listed as an employee. This began another period of royal service. In addition to managing the hotel and cooking at Marlborough House, he also cooked for special occasions at Sandringham. He apparently stopped cooking for the Prince and Princess of Wales in the late summer or autumn of 1866, and focused on the management and cuisine at the St. James’s Hotel thereafter. He catered regimental dinners, and had special dinners featuring particular ingredients (such as horse meat, and Liebig’s Extract of Meat (a concentrated beef extract)), and a parliamentary dinner. He resigned as manager of the hotel in March 1870.

In October 1870, he was hired as the manager of the Freemason’s Tavern, which was his last place of employment. He functioned as the sole manager and catered special dinners. He retired in June 1876, and died on August 10, 1876 in Eastbourne.

As we can plainly see, his career differed significantly from the way the writers depicted it in the series Victoria. His actual royal service comprised barely 2 years for Queen Victoria, and about 3 ½ years for the Prince and Princes of Wales over 20 years after leaving Buckingham Palace. As an entrepreneur, he parlayed his relationship with royalty, particularly Queen Victoria, into cookbook sales. What about his personal life? That was different, as well.

Far from falling in love with and marrying Mrs. Skerrett, the Queen’s Dresser (and there really was a Mrs. Marianne Skerrett who was the Queen’s Dresser), Mr. Francatelli was in fact married well before he went to work at Buckingham Palace to Elizabeth Roberts, the wife who assisted him in managing the St. James’s Hotel until her death March 2, 1869. Apparently, Mr. and Mrs. Francatelli had a daughter Emily and a son Ernest. Mr. Francatelli remarried the next year. He and Elizabeth Cooke were married August 2, 1870, and he evidently had children with her as well, including a son Charles Elme’ Francatelli born in 1875. There is no indication of any opportunity (or inclination) for a palace romance between Mr. Francatelli and any woman employed in Queen Victoria’s household. Again, his personal life was quite different from that depicted on the television series. This does not make the series any less enjoyable; however, it does illustrate the need to watch with caution, as the engaging romance shown does not always reflect what really happened.

Sources include:

Chancellor, E. Beresford. LIFE IN REGENCY AND EARLY VICTORIAN TIMES An Account of the Days of Brummell and D’Orsay 1800-1850. London: B. T. Batsford, Ltd., 1926.

Chancellor, E. Beresford. MEMORIALS OF ST. JAMES’S STREET and CHRONICLES OF ALMACK’S. New York: Brentano’s, 1922.

Erickson, Carolly. HER LITTLE MAJESTY The Life of Queen Victoria. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997. P. 237

Francatelli, Charles Elme’. A PLAIN COOKERY BOOK FOR THE WORKING CLASSES. Oxford: Benediction Classics, 2012.

Stephen, Sir Leslie, ed. DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY, 1921-1922. Vol. 7. London: Oxford University Press.

Colin Smythe Ltd. “Charles Elme’ Francatelli, Crockford’s, and the Royal Connection.” Copyright (c) 2014-2015 Colin Smythe. HERE

Find-a-Grave Memorial. “Charles Elme’ Francatelli.” HERE

Researching Food History-Cooking and Dining. “Queen Victoria’s chef Charles Elme Francatelli” Copyright © 2017 Patricia Bixler Reber (posted February 6, 2017). HERE

Crockford’s 1828: HERE

The Young Queen Victoria by Franz Xaver Winterhalter 1842: HERE

A Bill of Fare for Her Majesty’s Dinner: HERE

A Bill of Fare for Her Majesty’s Dinner: HERE

Receipt for Russian Salad from THE MODERN COOK 1846: HERE

~~~~~~~~~~

Lauren Gilbert is fascinated by England and its history, and multiple visits to England have only heightened her interest. A long-time member of JASNA since about 2001, she has attended multiple Annual General Meetings and was privileged to present a break-out session in Ft. Worth in 2011. Her first book, HEYERWOOD: A Novel was released in 2011, and she is a contributor to CASTLES, CUSTOMS AND KINGS True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors Volumes 1 and 2. She is finishing A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT and doing research for a biography. A long-time resident of Florida, she lives with her husband Ed. You can visit her website HERE.

~~~~~~~~~~

Lauren Gilbert is fascinated by England and its history, and multiple visits to England have only heightened her interest. A long-time member of JASNA since about 2001, she has attended multiple Annual General Meetings and was privileged to present a break-out session in Ft. Worth in 2011. Her first book, HEYERWOOD: A Novel was released in 2011, and she is a contributor to CASTLES, CUSTOMS AND KINGS True Tales by English Historical Fiction Authors Volumes 1 and 2. She is finishing A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT and doing research for a biography. A long-time resident of Florida, she lives with her husband Ed. You can visit her website HERE.

_Bartle_Frere,_1st_Bt_by_Sir_George_Reid.jpg)