by Kim Rendfeld

What did those Irish missionaries say to Richarius that made him give up what he knew and devote his life to Christ?

As with many early medieval saints, information about the seventh century Frank also known as Riquier is scant and contradictory, but the stories are tantalizing. Whether they’re true is up to the reader.

Richarius was born in a village then known as Centula in today’s France. Either he was working class guy who pursued rustic occupations or he was a nobleman, depending on which source you consult. With the events that follow, I think he was an aristocrat. Whatever his background, the visit of the two Irish missionaries, Caidoc and Fricor, changed his life.

When visitors arrived in Centula, they were mistreated by the locals. Except for Richarius, who offered his hospitality. After listening to their preaching, Richarius repented of his sins. So much that one story has him surviving only on barley bread strewn with ashes and water often mingled with his tears. Another has him offering protection to his guests so they could preach freely – something a nobleman could do.

| A 17th century illustration of St. Riquier Abbey (public domain) |

As an abbot, Richarius would be in a position of influence. He had control over land, which was power in early medieval times, and could make alliances among fellow noblemen, both lay and clergy. In addition, the medieval populace believed that prayers from the monks could sway events here on earth, including who won the battles.

During a visit from Frankish King Dagobert, Richarius impressed the monarch by giving him good advice, especially not to listen to flatterers, and the king rewarded him with a generous gift.

Richarius could have kept his place as abbot for life. Or if illness prevented him from performing his duties, he could retire in relative comfort at the monastery. Instead when his health was failing, he traveled 15 miles away to a forest and lived in a hut with only one companion, Sigobart.

| St. Riquier’s relics in the abbey he founded (photo by Paul Hermans, used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License) |

About 150 years later, that monastery, named St. Riquier, became a center for learning with Angilbert as its abbot. His close friend, Charlemagne, provided a golden shrine for the founder’s relics.

Images via Wikimedia Commons

Sources

Lives of the Saints, Omer Englebert

A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines: Naamanes-Zuntfredus Sir William Smith, Henry Wace

The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints, Alban Butler

Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne, Pierre Riché (translated by Jo Ann McNamara)

An Ecclesiastical History of Ireland, from the First Introduction of Christianity among the Irish to the Beginning of the 13th Century, John Lanigan

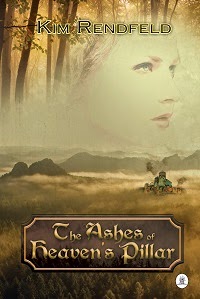

Kim Rendfeld’s latest release, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar (2014, Fireship Press), has a few scenes taking place at St. Riquier monastery 12 years before Angilbert became its abbot. During a trial there, the characters swear on a piece of wood from a tree the monastery’s founder liked to rest under. The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, Kim’s second book, is a tale about a medieval mother who will go to great lengths to protect her children. It is a companion to Kim’s debut, The Cross and the Dragon, in which a young noblewoman must contend with a jilted suitor bent on revenge and the anxiety her husband will die in the coming war.

Kim's book are available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other retailers. To read the first chapter of either book, get purchase links, or find out more about Kim, visit kimrendfeld.com or her blog Outtakes of a Historical Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com. You can also like her on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld, follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld, or contact her at kim [at] kimrendfeld [dot] com.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.