By E.M. Powell

No matter how ardent a fan of natural history documentaries you might be, you may struggle to identify the creature on the right portrayed in this medieval manuscript.

Yes, it's the serra, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as 'a fabulous marine monster.' The entry in the 1527 Noble Lyfe Bestes describes it thus: 'Serra is a fysshe with great tethe and on his backe he hathe sharpe fynnes lyke the combe of a cocke and iagged lyke a sawe.' While I think the serra is indeed quite marvellous, the OED means 'fabulous' in the sense of 'celebrated in fictitious tales.' But the medievals loved a fabulous creature and we find many examples of them in manuscripts and texts. I'd like to share a few personal favourites.

Dragon

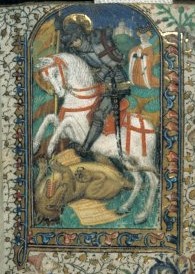

I doubt if anyone would struggle to describe a dragon: a mythical monster like a giant reptile, winged and breathing fire. Even today the national emblem of Wales is Y Ddraig Goch, The Red Dragon. This of course is a different type of dragon to the gwiber (viper). Celtic dragons were said to live at the bottom of deep lakes or guard trees and represent elemental power, often that of the earth. But with the spread of Christianity, the dragon came to represent paganism. For the medievals, the dragon was a symbol of demonic power or the sin of pride.

It features again and again as the vanquished opponent of the hero knight: Lancelot, Tristan and Gawain all fought and defeated dragons. Yvain rescued a lion from one. Dragons, sea serpents and giant worms appear on medieval maps, with the creatures representing wilderness and the unknown. Twelfth century chronicler Gerald of Wales viewed Ireland as a wild and inhospitable place but he reported in his Topography of that country, 'There are no dragons,' presumably good news to all.

It wasn't only knights who battled dragons during the medieval period. We can find over one hundred saints who had skirmishes with dragons or monstrous serpents. These include Saints Margaret of Antioch, Martha, Sylvester, Gregory and Armel. Most famously is England's Saint George. George may have been a soldier who achieved martyrdom in fourth century Palestine and had a modest reputation in the centuries that followed.

But it was a medieval bestseller that brought him huge popularity. The Legenda Aurea (The Golden Legend) was a collection of saints' lives compiled by James of Voragine and completed by 1265. In it, George excitingly saves a king's daughter who is about to be eaten by a dragon. George spears the beast, secures it with the princess's girdle and leads it before a huge city crowd where he beheads it. Everyone who sees it promptly becomes a Christian. Many miracles were attributed to him throughout the medieval period (usually the victory in battle kind) and by the end of the Middle Ages he was regarded as the patron saint of England.

Unicorn

According to medieval bestiaries, the unicorn was the wildest of all beasts and it was swift and fierce. The only way to capture it was for a virgin to stay close, whereupon the unicorn would lay its head in her lap, and so be able to be caught. The animal came to represent power and purity and the links to Christ and the Virgin resonated with the medievals. Wealthy collectors coveted unicorn horn as it was believed to have magical and medicinal powers, specifically against poison and convulsions.

Whatever these collectors believed they had paid for it certainly wasn't unicorn horn. No-one of course had actually seen one, although received wisdom was that the unicorn inhabited the Far East and India. One can only imagine the excitement when Marco Polo finally encountered one (several, in fact) in Java in the thirteenth century. Trouble was, the unicorn was actually a rhinoceros. We can hear Marco's disappointment at his discovery in his account of his travels: 'They delight in living in mire and in the mud. It is a hideous beast to look at. ' Most disappointingly of all: 'In no way like what we think and say in our counties, namely a beast that lets itself be taken into the lap of a virgin.' One can only concur: no-one, virgin or not, would want to give thigh room to a rhino.

Giants

The 1440 manuscript Sir Eglam has the appealing line: 'Ther dwellyth a yeaunt in a foreste.' A 'yeaunt' is of course a giant and many appear in medieval romances. We have another medieval bestseller to thank for their popularity. Geoffrey of Monmouth, Bishop of St Asaph in Wales, produced his Historia Regum Britanniae (‘The History of the Kings of Britain’) in around 1136.

In this work, King Arthur fights and slays giants. One of Arthur's quests is to seek the beard of one to make a leash for his dog. Geoffrey also says that Corineus, first human ruler of Cornwall, chose it because wrestling against giants was his favourite sport and Cornwall had lots of them. Gerald of Wales mentions giants bringing enormous stones to Ireland 'in ancient times.'

Representations of giants were also a popular feature of medieval pageants and processions. several major cities have records of their use. The figures were made from wood, wicker-work, and a coarse linen stiffened with paste. Many were brightly painted and were dressed in elaborate clothing. 1495 Chester had a family of them: giant, giantess, and two daughters.

Mermaid

In early use, the mermaid is often identified with the siren of classical mythology. Recorded from Middle English, the word comes from mere with the obsolete sense ‘sea’ and 'maid'. The 1366 Romaunt Rose observes: 'Though we mermaydens clepe hem here,..Men clepen hem sereyns in Fraunce.' (Note: that sentence is in Middle English. But you don't need a translation. Read it aloud just as it is written and it makes sense. It is also great fun to do.)

Medieval mermaids are, unsurprisingly, a sinful creature. They are specifically accused of inspiring lust and sinful desire. Heresy is another of their fishy evils. 'Syrens' pop up in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia and we are assured that many swim around the seas surrounding the British Isles.

Mandrake

Quick medieval thinking passed this fate onto a dog. Dog would be tied to mandrake, dog would be urged away from mandrake. Dog would pull it from the ground, so dog would die. Relief all round. In case you're wondering, that pale little chap in the picture above is a mandrake. People: if you see him amongst the carrots in your local supermarket, leave him alone. You have been warned.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

References:

All images are in the Public Domain and are part of the British Library's Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

Dear, I. C. B. & Kemp, Peter, eds: The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea (2 ed.) (Oxford University Press 2006 Current Online Version: 2007)

Kieckhefer, Richard: Magic in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press (2000)

Knowles, Elizabeth, ed.: The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (2 ed.) Publisher: Oxford University Press (2005, Current Online Version: 2014)

Lindahl, C., McNamara, J & Lindow, J. (eds.): Medieval Folklore, Oxford University Press (2002)

Livingston, E.A.,ed.:The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 rev.ed.), Oxford University Press (2006, Current Online Version: 2013)

MacKillop, James: A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology , Oxford University Press (2004, Current Online Version: 2004)

Resl, Brigitte, ed., A Cultural History of Animals in the Medieval Age. Oxford: Berg (2007)

Simpson, Jacqueline & Roud, Steve: A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford University Press (2003, Current Online Version: 2003)

E.M. Powell is the author of medieval thrillers THE FIFTH KNIGHT & THE BLOOD OF THE FIFTH KNIGHT which have both been #1 Historical Thrillers on Amazon's US and UK sites.

Sir Benedict Palmer and his wife Theodosia are back in book #3 in the series, THE LORD OF IRELAND. It's 1185 and Henry II sends his youngest son, John (the future despised King of England), to bring peace to his new lands in Ireland. But John has other ideas and only Palmer and Theodosia can stop him. THE LORD OF IRELAND is published by Thomas & Mercer in April 2016.

E.M. Powell was born and raised in the Republic of Ireland into the family of Michael Collins (the legendary revolutionary and founder of the Irish Free State) she now lives in the north west of England with her husband and daughter and a Facebook-friendly dog. Find out more by visiting www.empowell.com