By Mark Patton.

London's Victoria and Albert Museum currently has a major exhibition of English Medieval embroidery, including examples gathered from public collections around the World, and others from private collections never previously seen in public.

The Latin term,

Opus Anglicanum, refers to a school of English embroidery that had its origins in the Tenth Century, and flourished, especially, from the mid-Twelfth to the mid-Fourteenth Century. Most surviving examples are priestly and episcopal vestments, and the work of English embroiderers was so widely admired that these were in demand in all of Europe's great cathedral cities, and even in the Vatican itself. Domestic hangings were also made in the English workshops, but many fewer of these have survived.

|

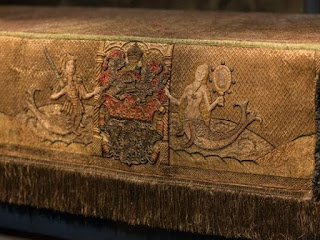

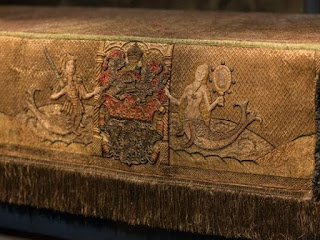

| The Butler-Bowden Cope, 1330-50, silk, silver and silver-gilt thread on Italian silk velvet (a cope is an outer vestment worn by a bishop or priest in a religious procession). Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum (licensed under GNU). |

|

| Cope from the Museum Schnutgen, Cologne. Photo: Raimond Spekking (licensed under CCA CC BY-4.0, via Wikimedia Commons). |

|

| Medieval cope-chest at York Minster (protecting vestments from light, damp, and vermin, such chests helped ensure their preservation). Photo: LeMonde1 (licensed under CCA). |

|

| The "funeral achievements" of Edward, the Black Prince, at Canterbury Cathedral, including an embroidered surcoat, a rare surviving example of secular embroidery. Photo: Jononmac46 (licensed under CCA). |

Among the earliest surviving examples is the stole found in the tomb of Saint Cuthbert, which was made between 909 and 916 AD. The "Bayeux Tapestry" (actually an embroidery) is another notable early example, and this commission was on such a scale that it may, in itself, have played a role in kick-starting the industry. It consists of a strip of

linen, a fabric that had been produced in England since the Bronze Age, embroidered with dyed woolen yarns.

|

| The Saint Cuthbert stole (a stole is a strip of fabric worn by a priest around his neck whilst administering a sacrament). Image is in the Public Domain. |

|

| The Bayeux Tapestry. Photo: Myrabella (licensed under CCA). |

Linen was, similarly, the basis for much of the later Medieval

Opus Anglicanum, although embroidered strips were sometimes sewn onto garments made of woven silk, imported from Italy, or from farther afield (Iran or Central Asia). The embroidery of the High Middle Ages made extensive use of silk thread, as well as gold and silver thread.

Raw silk was imported from China, via Italy: a cargo of oriental wares, including bales of silk, was unloaded at London by the Frescobaldi Company of Florence in 1304. From the late Fourteenth Century, however, most of the trade was in the hands of the Venetians, who imported dyed silk thread from the ports of Lahidjian and Talich, on the Caspian Sea. Each year, a fleet of Venetian galleys would sail out from the Mediterranean, half of them bound for London, and the other half for Flanders. They carried cotton and ivory, sugar, spices and wine, as well as silk thread; and returned with woolen cloth (England's most significant Medieval export), as well as embroidered vestments commissioned by Italian bishops.

|

| A Venetian "Flanders Galley," built to withstand Atlantic storms (illustration by Michael of Rhodes, a seaman who visited London in the 15th Century - image is in the Public Domain). |

Most of the English embroidery was produced in London, in the streets behind Saint Paul's Cathedral. The embroiderers were not, for the most part, monks or nuns, but private contractors, some of whose names are known: Adam de Basing, Maud of Canterbury, Mabel of Bury-Saint-Edmund's, Joan of Woburn, Maud of Bentley, Alice Prince, Matilda le Goldsherer. Whilst it is often difficult to untangle the precise nature of the supply chains, it seems that, whilst men such as Adam de Basing (Lord Mayor of London in 1251) handled much of the outward-facing business: negotiating with bishops, court officials, and Venetian sea-captains; much of the embroidery itself was done by women, who would have been among the best-paid professional women in Medieval society.

|

| The Fishmongers' Pall (used to cover the coffins of fishmongers during their funerals), 1512-38 (image is in the Public Domain). |

The industry declined from the mid-Fifteenth Century. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 disrupted the supply of silk, and, after 1517, the Protestant Reformation reduced the demand for sumptuously embroidered ecclesiastical vestments. Now, for the first time in my lifetime, some of this industry's finest masterpieces have been brought together in the city where most of them were made.

For more information about the exhibition, see the Victoria and Albert Museum website,

"Opus Anglicanum: Masterpieces of English Medieval Embroidery,"

This is an Editor’s Choice from the #EHFA archives, originally published November 10, 2016.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mark Patton blogs regularly on aspects of history and historical fiction at

http://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk. His novels,

Undreamed Shores,

An Accidental King, and

Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from

Amazon.

This embroidery is amazing and I'm not surprised that these women were well paid, though even the materials would have cost a fortune. When you think about the strain on the eyes doing this in a time where there was no electricity - well, if I was an embroiderer, I'd certainly want compensation.

ReplyDeleteThere was some gorgeous embroidery done in later centuries too. I went to see a glove exhibition in the costume museum in Bath once and was simply amazed at the delicacy and detail on Georgian embroidery.

Wonderful post. That cope is stunning.

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed this very much. Incredible workmanship. I'd love to see this exhibition. Thank you!

ReplyDeleteThe concentration of so many pieces in this exhibit was overwhelming. Everywhere you turned was another amazing example. There also was a video on how the embroidery was done that was very helpful. If you can go, you will be assigned a specific time to prevent too many bodies in the smallish hall at the same time.

ReplyDeleteFantastic article. Thanks so much

ReplyDelete