Wecome to the concluding part of Ælfgyva: The Mystery Lady of the Bayeux Tapestry.

Imagine someone wants to tell you some gossip about your neighbour Joe Bloggs, something quite scandalous and outrageous. Imagine that person has already heard it from someone else and perhaps that person has heard it from some other person. Imagine that somewhere along the line, facts have become distorted or left out. Perhaps someone has mistaken Joe for a different Joe – or for a John, who looked a lot like a Joe? Imagine that by the time the rumour reaches you, the whole episode has been scrambled into something slightly different, but with a similar concept? Perhaps the story is entirely the same, but the it is the identities of those involved that are morphed. Well, this is what I believe has happened in the Bayeux Tapestry with the Aelfgyva tale.

After studying the tapestry, the possible candidates and the possible links to the story quite thoroughly, I can come up with no other explanation other than it is a case of mistaken identity where a certain lady’s story has been wrongly attributed to another. One can imagine it would not have been that difficult to mistake one person for another when there were so many women with the same name around at the same time. Especially if you were a Norman, hearing scandalous tales passed from one person to another like a Chinese whisper.

So what are the implications of such a suggestion? This is what I believe, could be… what the Bayeux Tapestry is trying to convey. It is not a hypothesis that can be proven, but merely a suggestion and an interpretation of what this scene might signify. I am not in any way stating that I have cracked the mystery, or that I have finally found the answer. I am however presenting you with a possibility, having been unable to discover any other indisputable explanation for the woman’s role embroidered into the legend with the hints of scandal that have been attributed to a particular woman of that name.

So, here is the story, as I imagine it:

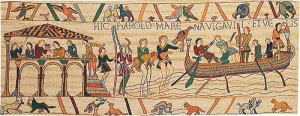

|

| Harold embarks from his home in Bosham to Normandy with his personal guard. |

The woman in the scene with the cleric, is Ælfgifu of Northampton, and the priest touching her face is doing so to signify some sort of collaboration with her. In the scene before, Harold and William are discussing the earl’s reasons for coming to Normandy. The scene in which Ælfgyva and the priest are portrayed is part of their conversation also. Harold is explaining to William that he has come to negotiate the release of his brother and nephew, hence the man that Harold appears to be almost touching with his finger, is presented with a beard in the English style of facial fashion, and not the Norman clean-shaven manner, as all the others in the scene are – apart from Harold, of course. It seems quite reasonable to me that this bearded fellow is Wulfnoth, Harold’s brother who was one of the hostages he has come to negotiate the release of.

But William, overwhelmed by the earl’s presence and its implication for him, understands some other reason for Harold’s visit. He is convinced that Harold has come to declare his fealty to him and assure him that when Edward dies, he will support him as his successor. Why else would he come with such gifts of wonder to offer him? Could William’s mindset have been so focused on the crown of England that he cannot not hear the words Harold is trying to say to him?

Harold mentions, carefully – very carefully – because Edward, the king, has told him to be so, that King Edward has declared his great nephew, Edgar, grandson of the courageous Edmund Ironside, as the atheling, which means that the boy is someone who is throne-worthy, therefore a future candidate to the throne. Harold knows that William has never been named atheling, but he is very careful how he presents his case. William listens, shows interest in what the Englishman has to say, after all he is going to need him when Edward dies. Nonetheless, he is undaunted by what Harold is telling him. He has already dismissed Edgar, having heard the scandal of Edmund Ironsides’ mother Aelfgyva, who it was said, had tricked her husband into believing her sons were his when they were really the sons of a priest and a workman. He laughs at Harold’s suggestion that the Witan should prefer a boy over a man such as him, a boy descended from dubious lineage. Is he not (the duke) a man who has cheated death many times and earned the respect of his enemies?

Harold tries to put him straight about Ælfgyva, desperately trying to make him understand that he is mistaken and that the woman in the scandal he was referring to was not Edmund Ironside’s mother, but Harold Harefoot’s mother, wife of Cnut. Yes, Aethelred’s wife was also called Ælfgifu, but there was no such scandal about her and Edgar’s lineage is indisputably of the true line of Wessex.

Still William does not listen. He interrupts, rebuffs and insists – all in the best nature and good spirits, of course. Harold is having problems pressing home his point because William has made his mind up. It is a game that only William can win. Harold, William declares, will support him in his quest for the English throne, and consider allying himself closely to him by marrying a daughter of his. William suggests this proposition in such a way that if Harold should refuse, he may inflict great insult upon his most congenial host, who has saved him from the humiliation and torment of being held as the Count of Ponthieu’s prisoner... and in Harold’s mind, he is thinking that if he wants to leave there alive, he will have to play the game that William has already won. Perhaps it is then that Harold realises what a terrible mistake he has made. Why, oh why, did he not listen to his king when he warned him that “no good will come of it”?

|

| William knights Harold and makes him his vassal |

So any attempt that Harold might make to put right the error that William has made in identifying the correct scandal with the incorrect Ælfgifu, is from then on thwarted. Wiliam will change the subject or offer a distraction. He does anything not to talk about the subject again. And by the time he gets home, with only one of the hostages being released, Harold is ridden with anxiety, having been made to swear an oath on holy relics, that he has basically handed the English crown on a plate, to the Norman duke. The first thing he does is seek out his relative, Ælfric, who was once a monk at Canterbury, and in earnest, divulge to him what he has done. It is then that Harold learns that according to canon law, a man who gives oath under severe duress, can later recant without detriment to his soul. With this knowledge, Harold can later go on to forgo the oath he made to William, to take the crown for himself. Which he does, indeed, later in 1066.

Did the artist who designed the tapestry know the secret of the conversation that happened between Harold and William? Were they trying to convey the story that led to the mis identity of Ælfgifu and coerced oathtaking that meant the end of Anglo-Saxon rule? We shall never know, but this is the possibility that I have come to believe. How I wish I had a time machine, so that I could take you back with me to that year, 951 years ago when it all happened.

*

I believe that this is the basis for the artist’s insertion of the scene with Aelfgyva and the priest. Whether or not my theory is right, the creator wanted to convey to the viewer that this particular scandal had some link to the conversation that William and Harold are having. The small, crude images in the border further enforces the story of Aelfgifu of Northampton’s scandal leaving me with no doubt that they represent the labourer and priest who were supposed to have fathered the children said to be Cnut’s sons. I cannot, although I have tried to, locate any other evidence that would identify a believable rationale for this scandal to have been placed in the tapestry.

If I were a contemporary of it, I may have been privy to the tittle-tattle and also that perhaps William had wrongly identified the woman and would not have had to use my imagination to work out the innuendo of the illustration. But this is my interpretation. Unfortunately I have no way of knowing I am right, however I do not think this has been a pointless study, for it has identified the woman and shed some light on some other mysteries of the tapestry also. I hope that you all have not been disappointed.

I would love to know what you think.

References

Bridgeford A. (2004) 1066 The Hidden History of The Bayeux Tapestry, Harper Perennial, London.

Eadmer Eadmer’s History of Recent Events in England

Eadmer Historia Novorium in Anglia

Eric Freeman in his Annales de Normandie

Harvey Wood H, (2008) The Battle of Hastings: The Fall of Anglo Saxon England, Atlantic Books, Chatham.

McNulty J.B. (1980) The Lady Aelfgyva in the Bayeux Tapestry, Medieval Academy of America, vol 55 (4) pp 659-688.

~~~~~~~~~~

Paula Lofting is an author and a member of the re-enactment society Regia Anglorum, where she regularly takes part in the Battle of Hastings. Her first novel, Sons of the Wolf, is set in eleventh-century England and tells the story of Wulfhere, a man torn between family and duty. The sequel, The Wolf Banner is available now. Paula is currently working on the third book in the series, Wolf's Bane

Find Paula on her Blog - The Road to Hastings & Other Stories

on her Amazon Author Page

Read the rest of this blog series:

Great series, Paula! I can't imagine the hours that have gone into it.

ReplyDeleteThank you, quite a lot, i do think!

DeleteI think you've used your novelist's imagination as a skilful tool of enquiry. I think imagining possibilities is a good thing. Most definitely, in my opinion, Ælfgyva and the cleric are being talked about by Harold and William. Your explanation is very plausible. Where I differ with you is on the specific meaning of the figures in the border below. Exposed male genitalia (both human and equine) are used elsewhere in the Tapestry in a context of machismo and overbearing masculinity. The posturing of the squatting figure mirrors that of the cleric (whoever he is) and attributes to him a dominant controlling demeanour. Similarly the naked fellow working away with his ax, positioned under the conversing William and Harold, alludes to the nature of their meeting; to use modern day idiom, you can smell the testosterone. There's also a peacock in the roof above William, and this adds to the sense of prideful machismo evident in the verbal labours of the two noblemen. This is in condensed form what I wrote about this scene in an essay for the book on the Tapestry published last year by Manchester Uni Press. It's way too expensive to buy, but if you wish I can find a way to get the info to you. I do think your arguments are very worthwhile making, especially concerning the identity of Ælfgyva. Certainly I didn't have the confidence to weigh into that particular debate but my strength is more in understanding gesture and symbolism in early medieval art and so I took a different approach by looking at male genitalia more broadly (as one does :-)).

ReplyDeleteHi Christopher, yes this is the theory that I wil be using when i get to this part in my Sons of the Wolf fictional series about the events leading up to 1066. And yes, my novelist's enquiringly mind compels me to find reasoning for the meanings and actions of historical evidence and character's behaviours. Which is why i needed to find a plausible identity for her and then link her to the story. Historians and archaeologists are more interested in interpretations but not necessarily the links between evidence that will give meaning and rationale to what we see and know. hoping that makes sense. In writing a novel, one has to present a plausible story. This is mine. Thanks for reading and taking the time to comment.

DeleteNone of you seem to know that there is already a novel out, about Aelfgyva, and the plot is very plausible. It is called The Needle in the Blood, by Sarah Bower, published in 2007. We do know from the historians that Bishop Odo of Bayeux had an unofficial wife, and she had a son. You only have to assume that she was called Aelfgyva, and all is explained, as in the novel.

ReplyDeleteYes I know this book and it is a very good book, but totally fiction and I would disagree that it is plausible.

DeleteHere is my latest theory, in brief. The Bayeux Tapestry was designed by Scolland, the Breton/Norman Abbot of St Augustine’s Abbey in Kent. His main informant is the Breton commander Alan Rufus, standing behind the bearded man who is indeed Wulfnoth.

ReplyDeleteNakedness represents exposure of vulnerability or shame. The naked figure below with the wood tool is a rebus for Hakon, Swein’s son.

The next naked man represents Swein himself, lewdly approaching Ælfgifu (Ælfgyva), Abbess of Leominster in Hereford, whom Swein abducted in 1046. (The columns are topped by lions: Leo.)

The cleric may be Ealdred, Bishop of Worcester (later Archbishop of York) who met Swein in 1050, perhaps to absolve him of his sin, and helped restore to his Earldom. In this scene, Ealdred is giving spiritual counsel to Ælfgifu: they are both clothed, so this is in contrast to the scene in the lower margin: evil deed (and man) below, righteous one above.

Hypothesis: Hakon is Ælfgifu’s son by Swein, a scandal indeed.

William will allow only one of Harold’s kinsmen to be redeemed: Harold’s choice. Earl Harold is pointing to Wulfnoth: I’ll take my brother. Wulfnoth is pointing down: No, I insist on staying. You must take our nephew Hakon, Swein’s only son.

Very interesting, Zoe.

Delete