The rigid class structure of medieval society has frequently mislead casual students of the period to assume that there was little to no social mobility in the Middle Ages. While it is certainly true that it was impossible for a serf to become a king or vice versa, and individuals were largely confined to their broad social strata, society was far less stagnant than frequently alleged.

The accumulation of wealth was, then as now, the best means of upward mobility. Contrary to popular opinion, archeological evidence suggests that many peasants, even serfs, could through hard work, judicious management, clever marriage alliances (and luck, of course) acquire substantial land-holdings. They built large, comfortable houses comparable to manor houses, and could, when circumstances favored them, buy their freedom. The first step of the ladder.

Freemen likewise had opportunities for the accumulation of wealth, and already by the 12th Century there were merchants in major cities such as London, Southampton, and York that could afford grand houses (by the standards of their day) often surpassing the houses of poorer nobles and gentry. The very need for sumptuary laws in the 14th century underscores the degree to which wealth attained through trade or industry had started to surpass the wealth of the landed aristocracy making the latter jealous of the former.

The Church, of course, had always offered the sons of peasants opportunities for advancement. A particularly bright boy could be given to the Church (with the consent of his landlord, who would hardly be in a position to refuse), and if very talented that peasant boy could theoretically rise to very high office. Thomas Becket is perhaps the most prominent English example of a youth of “low” (in this case merchant) birth rising to the highest ecclesiastical office in the Kingdom. More common and still a step upward, youths of peasant origin with a church education could become household officials to the nobility as clerks, stewards, confessors and chancellors. The Templars and Hospitallers, meanwhile, reserved certain senior offices within the Orders for non-noble members.

Another avenue for upward mobility — and one of only two open to girls — was, of course, marriage. Marriage in the Middle Ages was concluded between families for material/political gain. While this usually entailed marrying within one’s class, the English nobility, in contrast to the French, recognized the advantages of marrying money, particularly the daughters of the fabulously wealthy wool merchants of the High Middle Ages. Such a practice benefitted both parties, of course, because not only did the bride take on her husband’s title, but her brothers and sisters, nieces and nephews could henceforth expect patronage from her noble husband. As a result of such alliances, youth of non-noble birth acquired access to training as squires and so knighthood as well.

The other option for girls was, of course, to become the mistress of a great lord or the king. This was considerably more risky as men’s affection could prove short-lived. But the more successful courtesans generally obtained for their family members as well as themselves significant material advantages for as long as they were in favor. These in turn could be used to advance the entire family socially. In very rare instances, such as the case of Katherine de Roet, the liaison might even be legalized; after being John of Gaunt’s mistress for years and giving him four bastards, Katherine eventually became John of Gaunt’s third wife and died as Duchess of Lancaster.

But marriage for men could also be a stepping stone upwards. Admittedly, no family willingly gave a daughter to a man of significantly lower birth, but the guardians of heiresses were much less scrupulous. Indeed, one of the most important means by which a king could reward a favorite was through the award of an heiress. A man who married an heiress acquired the titles and lands that went with her regardless of his own social background. Thus, for example, William Marshal, a landless younger son, gained his barony by marriage to the heiress of Pembroke.

Royal service, of course, offered yet another means of advancement. Here the opportunities were various from battlefield knightings to royal appointments. I have already mentioned Thomas Becket, but another good example is the above mentioned William Marshal. Born the fourth son of John Marshal, he started out in life with nothing but his horse and his armor, the former of which he promptly lost in a melee. He took service, as was usual, with a maternal uncle and here had a stroke of luck. While he as part of his uncle’s retinue escorting Queen Eleanor across her own territories in Poitou, they were attacked by the rebellious Lusignan brothers, who promptly killed William’s uncle in an ambush. William himself fought fiercely, bareheaded and on foot, against 68 men (according to his 13th century biographer) killing six before he himself was gravely injured and carried off a hostage. This act of youthful courage earned him the enduring gratitude of not only the Queen of England, but her husband, Henry II. William Marshal was taken into the royal household where he served with sufficient skill, diligence and discretion to be appointed tutor-in-arms to Henry the Young King. Although his rise was not always easy and he encountered a number of set-backs, he would eventually rose to Regent of England, ruling for the under-aged Henry III.

And as long as there was a Christian presence in the Holy Land (Outremer), there was always the option of going East to seek one’s fortune there. Fulcher of Chartes, the chaplain of Baldwin of Boulogne, wrote of the crusader kingdoms:

Every day relatives and friends arrive from the West come to join us. They do not hesitate to leave everything they have behind them. Indeed, by the grace of God, he who was poor attains riches here. He who had no more than a few deniers finds himself here in possession of a fortune. He who owned not so much as one village finds himself, by God’s grace, the lord of a city.

Bartlett, W.B., Downfall of the Crusader Kingdom, The History Press, 2007, p. 189.

While Fulcher of Chartes was undoubtedly and unabashedly seeking to encourage immigration to the Latin East, he did not exaggerate. Peasants had to receive their freedom to be able to participate on a crusade, and if they made it to the Holy Land and chose to settle there — as tens of thousands did — they settled as free men and burghers, not serfs. But it was the younger sons of obscure European noblemen that took the greatest prizes: Barison (of unknown and possibly non-noble origin) received the newly built castle of Ibelin, married the heiress of Ramla, and paved the way for his descendants to become queens and regents of both Jerusalem and Cyprus. Reynald de Chatillon married the widowed Princess of Antioch to become a prince. And Guy de Lusignan, the third son of Poitevan nobleman, took the greatest prize of all: he married the widowed Princess of Jerusalem and became a king.

In short, there were many more opportunities for social mobility in the Middle Ages than is popularly assumed.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

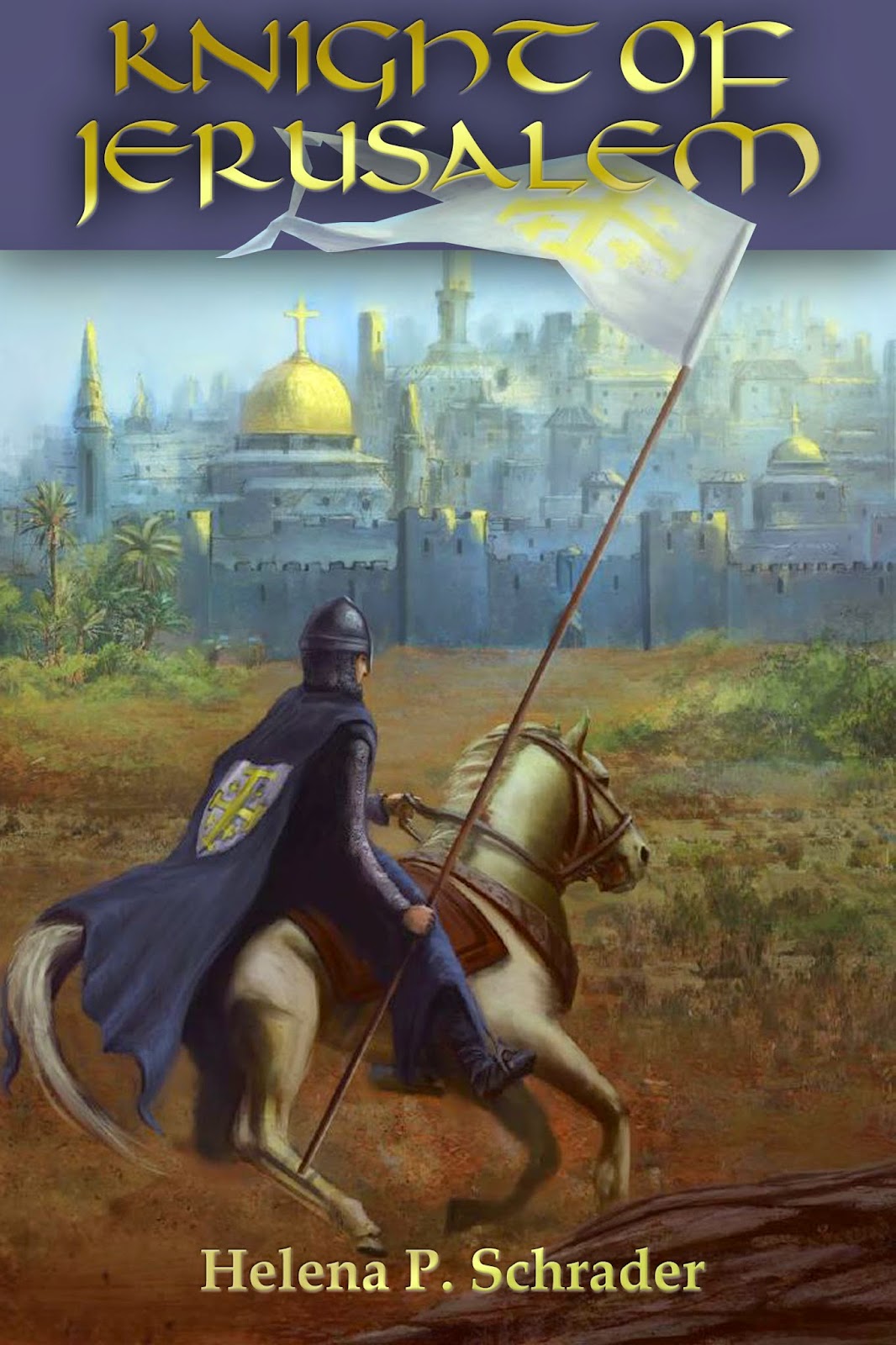

Helena P. Schrader is the author of numerous works of history and historical fiction. She holds a PhD in History from the University of Hamburg. The first book of a three-part biographical novel of Balian d’Ibelin, who defended Jerusalem against Saladin in 1187 and was later one of Richard I’s envoys to Saladin, is now available for sale. Read more at: http://helenapschrader.com or follow Helena’s blogs: Schrader’s Historical Fiction and Defending the Crusader Kingdoms.

A Biographical Novel of Balian d’Ibelin

Book I

A landless knight,

A leper King

And the struggle for Jerusalem.

Thanks really interesting. I've always found Becket and William Marshal to be two of the most interesting examples of social mobility in their time periods. I was wondering do you know of any examples of wool merchants daughters marrying nobility? It's something I've been looking at for something I'm writing but I have as yet not found concrete examples.

ReplyDelete