by Mark Patton

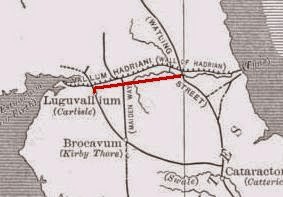

The Roman fort of Vindolanda often features in the itinerary of visitors to Hadrian's Wall, but it is earlier than the wall itself and located some distance to the south. The first wooden fort was built in around 85 AD by the First Cohort of Tungrians, and this was replaced by a larger fort, built ten years later by the Ninth Cohort of Batavians, numbering around a thousand men (both were auxiliary units recruited in different parts of what are now the Netherlands and Belgium). Further construction work was undertaken in around 100 AD under an officer named Flavius Cerealis, of whom there is more below. The fort was built to protect Stane Street, the main Roman road running through northern Britain from east to west.

The most remarkable aspect of the archaeology of the fort is a series of letters, written in ink on tablets of thin wood. It is very unusual in northern Europe for such materials to survive, but the waterlogged conditions at Vindolanda have made this possible, and the letters give us a unique perspective on both military logistics and family life in Roman Britain.

This letter, for example, is from one officer to another.

"Octavius to his brother Candidus, greetings. The hundred pounds of sinews from Marinus, I will settle up ... I have several times written to you that I bought about five thousand modii of grain, on account of which I need cash. Unless you send me some cash, at least five hundred denarii, the result will be that I shall lose what I have laid out as a deposit ... and I shall be embarrassed ... Make sure that you send me cash, so that I have ears of grain on the threshing floor ... I have already finished threshing all that I had." http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk/TVII-343.

Octavius and Candidus were not necessarily brothers in the biological sense. It is a common form of greeting between Roman soldiers, and it is unclear whether it has a specific meaning (they might, for example, have been "brothers" in the Cult of Mithras). Octavius is presumably procuring supplies from local farmers to feed his men, but cannot pay those farmers until he receives money from elsewhere. One can easily imagine the consequences of not receiving the funds, but also the practical difficulties involved (the same letter refers to the risk of injuring animals "whilst the roads are bad" - presumably because of inclement weather).

Not all of the letters involve military logistics. This one is between two women.

" ... greetings. Just as I had spoken with you, sister, and promised that I would ask Brocchus and would come to you, I asked him and he gave me the following reply, that it was always readily permitted to me ... to come to you in whatever way I can ... Greet your Cerealis from me. Farewell my sister, my dearest and most longed-for soul. To Sulpicia Lepidina, wife of Cerealis, from Severa, wife of Brocchus." http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk/TVII-292.

Severa has asked her husband for permission to visit her friend, Sulpicia Lepidina. Sulpicia is the wife of Flavius Cerealis, the prefect at Vindolanda, who is also the commanding officer of Severa's husband, Brocchus. The final greeting is in a different hand to the body of the letter, so the likelihood is that Severa dictated the letter to a slave, but added the greeting herself.

Both soldiers (Cerealis & Brocchus) have their wives and families living with them (there is another letter, in which Severa invites Lepidina to her birthday party, and mentions her little son). There are enough letters mentioning the same people to enable us to begin to understand something of their individual characters, and the dynamics of their relationships. Other letters refer to the supply of iron, beer, wine and leather; and the prices of these commodities.

All of the letters are accessible online (both in Latin and in English translation) at http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk. Some of the originals can be seen at the British Museum. Until very recently, the Vindolanda tablets were absolutely unique in the context of Roman Britain, but recent excavations in London have revealed similar caches of documents, most of which have yet to be transcribed and translated. I am looking forward to meeting a whole new cast of characters when they are published!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mark Patton blogs regularly on historical themes and historical fiction at http://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk. His novels, Undreamed Shores and An Accidental King, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

The Roman fort of Vindolanda often features in the itinerary of visitors to Hadrian's Wall, but it is earlier than the wall itself and located some distance to the south. The first wooden fort was built in around 85 AD by the First Cohort of Tungrians, and this was replaced by a larger fort, built ten years later by the Ninth Cohort of Batavians, numbering around a thousand men (both were auxiliary units recruited in different parts of what are now the Netherlands and Belgium). Further construction work was undertaken in around 100 AD under an officer named Flavius Cerealis, of whom there is more below. The fort was built to protect Stane Street, the main Roman road running through northern Britain from east to west.

|

| The military bath-house of Vindolanda. Photo: "Optimist on the run" (licensed under CCA). |

|

| Stane Street. Image: "Neddyseagoon," (licensed under GNU). |

The most remarkable aspect of the archaeology of the fort is a series of letters, written in ink on tablets of thin wood. It is very unusual in northern Europe for such materials to survive, but the waterlogged conditions at Vindolanda have made this possible, and the letters give us a unique perspective on both military logistics and family life in Roman Britain.

This letter, for example, is from one officer to another.

|

| Vindolanda Tablet II.343. Photo: Michel Wal (licensed under GNU). |

"Octavius to his brother Candidus, greetings. The hundred pounds of sinews from Marinus, I will settle up ... I have several times written to you that I bought about five thousand modii of grain, on account of which I need cash. Unless you send me some cash, at least five hundred denarii, the result will be that I shall lose what I have laid out as a deposit ... and I shall be embarrassed ... Make sure that you send me cash, so that I have ears of grain on the threshing floor ... I have already finished threshing all that I had." http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk/TVII-343.

Octavius and Candidus were not necessarily brothers in the biological sense. It is a common form of greeting between Roman soldiers, and it is unclear whether it has a specific meaning (they might, for example, have been "brothers" in the Cult of Mithras). Octavius is presumably procuring supplies from local farmers to feed his men, but cannot pay those farmers until he receives money from elsewhere. One can easily imagine the consequences of not receiving the funds, but also the practical difficulties involved (the same letter refers to the risk of injuring animals "whilst the roads are bad" - presumably because of inclement weather).

Not all of the letters involve military logistics. This one is between two women.

|

| Vindolanda Tablet II.292. Photo: Michel Wal (licensed under GNU). |

" ... greetings. Just as I had spoken with you, sister, and promised that I would ask Brocchus and would come to you, I asked him and he gave me the following reply, that it was always readily permitted to me ... to come to you in whatever way I can ... Greet your Cerealis from me. Farewell my sister, my dearest and most longed-for soul. To Sulpicia Lepidina, wife of Cerealis, from Severa, wife of Brocchus." http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk/TVII-292.

Severa has asked her husband for permission to visit her friend, Sulpicia Lepidina. Sulpicia is the wife of Flavius Cerealis, the prefect at Vindolanda, who is also the commanding officer of Severa's husband, Brocchus. The final greeting is in a different hand to the body of the letter, so the likelihood is that Severa dictated the letter to a slave, but added the greeting herself.

,_Vindolanda_Roman_Fort_-_geograph_org_uk_-_409012.jpg) |

| The headquarters building at Vindolanda in which Flavius Cerealis had his offices. Photo: Phil Champion (licensed under CCA). |

Both soldiers (Cerealis & Brocchus) have their wives and families living with them (there is another letter, in which Severa invites Lepidina to her birthday party, and mentions her little son). There are enough letters mentioning the same people to enable us to begin to understand something of their individual characters, and the dynamics of their relationships. Other letters refer to the supply of iron, beer, wine and leather; and the prices of these commodities.

|

| Altar dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus from the vicus (the civilian settlement around the fort) of Vindolanda. Photo: Alun Salt (licensed under CCA). |

All of the letters are accessible online (both in Latin and in English translation) at http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk. Some of the originals can be seen at the British Museum. Until very recently, the Vindolanda tablets were absolutely unique in the context of Roman Britain, but recent excavations in London have revealed similar caches of documents, most of which have yet to be transcribed and translated. I am looking forward to meeting a whole new cast of characters when they are published!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mark Patton blogs regularly on historical themes and historical fiction at http://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk. His novels, Undreamed Shores and An Accidental King, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon UK or Amazon USA.

Thank you so much for your post. I am so happy to learn that these letters are accessible online in English. I've been wanting to read them.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Annina, the online translations appeared quite recently, I think - the printed volumes are quite expensive and I had been consulting them at the British Library.

ReplyDeleteIndeed, thank you, Mark. It is one of the essential elements of historical fiction that we recognize the humanity (and banality at times) of our ancestors. This post makes that point most compellingly.

ReplyDeleteIt's true, Helena, that these folks certainly weren't competing with Pliny the Younger, but precisely because of that, they give all sorts of fascinating little details about aspects of their lives which he wouldn't mention, probably because his slaves took care of those details without him even being aware of them.

ReplyDeleteBrilliant post, Mark. A glimpse into 'real lives'.

ReplyDeleteThank you for another source- Mark. I was at Vindolanda some years ago but, of course, not everything was available for public viewing.

ReplyDelete