|

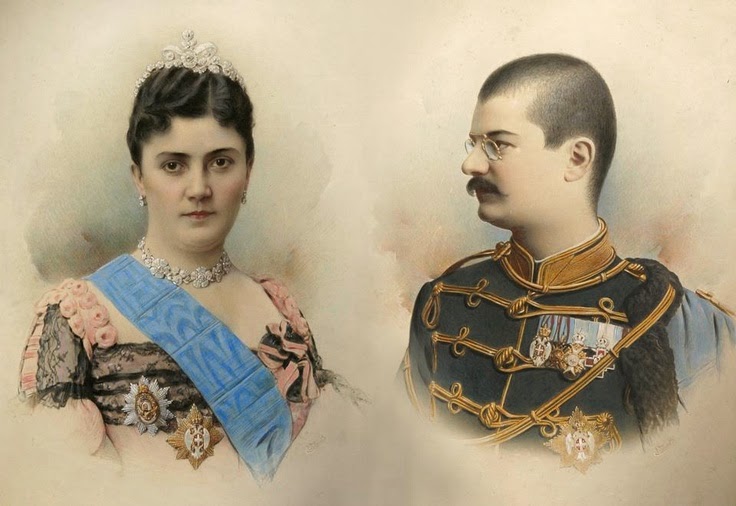

| King Alexander and Queen Draga |

While searching for current affairs items which could be discussed over the teacups in Flora's drawing room, I discovered the assassination of a royal couple which almost equalled the atrocity of that of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie in Sarajevo on June 28th 1914, which was the catalyst for the start of World War I. These assassinations took place almost ten years before, known as The May Coup, had an equally traumatic effect on the Austro Hungarian relations.

In 19th Century Serbia, a bitter feud existed between two of the country’s leading families; the Obrenovich and Karageorgevich dynasties, both of whom struggled for independence from the Turks. The original Karageorge (‘Black George’) was murdered in 1817 by his rival Milos Obrenovich, who had him killed with an axe and sent his head to the Sultan in Constantinople. During Serbia’s gradual emergence from the Ottoman Empire, the two families alternated as rulers.

The story of King Alexander of Serbia and the woman he chose to be his wife is a classic case of an immature, lonely boy being entranced by an older woman he refused to live without.

Alexander’s Parents

At twenty-two, King Milan Obrenovich I married the beautiful, sixteen-year-old Moldavian, Natalie [Natalija or Nathalie] Keshko. Their only child, Alexander was born a year later. King Milan was an unpopular, autocratic ruler, nor was he a faithful husband. Queen Natalie was reputed to be hot-headed, impulsive and indiscreet. After ten years, they separated and Queen Natalie left Serbia taking ten-year old Prince Alexander, known as Sascha, with her. King Milan removed the Crown Prince from her influence by force, apparently by police while the boy was clinging desperately to his mother. His father took him to Belgrade and took charge of his education.

|

| King Milan I |

Sascha was devoted to both his parents, but the influence exercised by his father led to misunderstandings between the boy and his mother, used by both in their quarrels where he was required to side with each in turn.

In 1882 Milan Obrenovich, the reigning prince, declared himself King of Serbia, but abdicated in 1889 and went to live in Paris, leaving his twelve-year-old son Alexander as king under a council of regency.

At sixteen, Alexander proclaimed himself of age, dismissed the regents and their government, abolished his father’s liberal constitution and restored a conservative one, then brought his father Milan, and appointed him commander-in-chief of the Serbian army, though this didn't last and Milan left again.

After a great deal of unpleasant publicity, not to mention the to-ing and fro-ing of each of them between Belgrade and their chosen locations of exile, the King and Queen of Serbia divorced in October 1888, after thirteen years of marriage, although later this was declared illegal. Nathalie was in her twenty-eighth year, and considered one of the most beautiful women in Europe.

|

| Queen Nathalie |

Draga [which means ‘dear’ or ‘precious’ in Serbian] Lunjevica, was the daughter of a prominent Serbian family, married an engineer named Svetozar Maschin at fifteen and widowed at eighteen. She had two brothers, Nikola (Nicholas) and Nikodije (Nicodemus) and four sisters, Hristina (Christine), Đina, Ana (Anne) and Vojka.

|

| Draginja Milićević Lunjevica Maschin |

Dismissed from the Queen’s service, Draga immediately returned to Belgrade, where she acted as King Alexander's adviser, so before long, he felt he could not live without her.

King Milan, alway broke, wanted a wealthy American for his son, and he too was outraged at Sasha's relationship with Draga, a commoner. However, under

King Milan, alway broke, wanted a wealthy American for his son, and he too was outraged at Sasha's relationship with Draga, a commoner. However, underQueen Nathalie's hopes for Sasha's future wife included the younger Infanta of Spain. Other Princesses of the reigning Houses of Europe on her list included the Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia, the Princess Sybille of Hesse-Cassel, the Princess Xenia of Montenegro, and more than one of the numerous Archduchesses of Austria.

One may be forgiven in thinking his mother’s love was somewhat blind, as an ex attaché wrote of Alexander:

|

| King 'Sasha' of Serbia |

When the engagement was announced, the entire Đorđević's government resigned and Alexander had difficulty in forming a new cabinet. Alexander had Đorđe Genčić, Minister of the Interior, jailed for seven years for his public condemnation of the engagement. Queen Natalie was subsequently banished from Serbia for expressing her displeasure, the situation finally resolved by Russian Tsar Nicolas Romanov who agreed to be Alexander's honorary best man.

The wedding took place on 23 July 1900; she was thirty-two; he was twenty-three. On hearing that the marriage had taken place Queen Nathalie said:

‘We must hope that this comedy, for I can speak of it by no other name, may not turn into a most fearful tragedy.’

Rumours of Draga’s pregnancy started soon after the wedding, but those in her private circle knew her to be infertile after a youthful accident, which Alexander refused to believe, although the pregnancy did not materialise.

|

| Draga and two of her sisters |

Draga was immediately raised to the position of Queen of Serbia, with equal rights to reign with the King. Various institutions founded by Queen Nathalie, and which bore her name were re-named as Queen Draga institutions, and the queen's Serbian regiment was given to her daughter-in-law. These petty acts did nothing to increase the new queen’s popularity. Draga knew this and was terrified her enemies would poison her and had all of her food tasted.

Within a year, Queen Natalie pressured Alexander to divorce Draga, while Draga thought Alexander was being corrupted by power and cared only for himself. Then a story circulated that Draga was trying to get her sister to have a baby and pass it off as her own, and that she had killed her first husband.

Discontented army officers plotted in September 1901 to kill Alexander and Draga with knives dipped in potassium cyanide at a party for the Queen's birthday on 11 September, but the plan failed since the royal couple never arrived.

By March 1903, there was rioting around royal residences, and a growing anti-monarchist movement throughout Serbia. Prince Peter Karageorgevich, almost sixty and the grandson of Black George, had spent much of his life in exile serving in the French army, but with Draga childless and discontent mounting, saw himself as a candidate for the Serbian throne.

Then a rumour started that Draga tried to have her brother, Nikola Lunjevica, named heir to the throne. Nikola was a junior military officer who threw frequent temper tantrums and once killed a policeman whilst drunk. As the king's brother-in-law, he had also demanded senior officers report to and salute him.

|

| Colonel Dragutin Dimitriević, [Apis] |

Draga and Alexander heard the crowd approaching and hid in a cupboard in Draga’s bedroom where they held each other and tried to keep quiet.

|

| King Alexander and Queen Draga |

While Apis lay wounded in the basement of the palace, the conspirators ordered the King's first aide-de-camp, General Lazar Petrović to tell them if a secret room or passage existed in the palace. Petrović peacefully waited for the deadline of ten minutes to expire, then what happened next is not recorded in detail, but when finally the doors were shattered with dynamite, the conspirators found the bed empty.

The couple were found in a secret room behind a mirror or in an alcove - the accounts vary. When the partially dressed Alexander and Draga emerged, three officers emptied their revolvers into them, killing Draga and wounding Alexander, who frantically clung to the balcony until an officer drew his sword and cut off his fingers.

|

| Contemporary artist's impression of the killings |

The Prime Minister Dimitrije Cincar-Marković and the Minister of the Army Milovan Pavlović also died that night. The Queen’s brothers Nikodije and Nikola Ljunjevice were shot by a firing squad.

The National Assembly voted Peter Karađorđević as King Peter I, but international outrage came swiftly, with both Russia and Austria-Hungary condemning the assassinations. When no attempt was made to bring the assassins to justice, The United Kingdom and the Netherlands withdrew their ambassadors from Serbia, froze diplomatic relations, and imposed sanctions. British Prime Minister Arthur Balfour condemned the assassinations saying that Ambassador Sir George Bonham was only accredited in front of King Alexander, thus with his death, relations between United Kingdom and Serbia were terminated and Bonham left Serbia.

|

| The open window from where Alexander and Draga were thrown |

Russia returned its ambassador after a short, placatory negotiation, followed by other states, leaving only the United Kingdom and the Netherlands alone in boycotting the new Serbian government. British-Serbian diplomatic relations were renewed by decree signed by King Edward VII three years later in 1906.

After the coup, the Black Hand became increasingly powerful, thus King Peter exerted minimal interference in politics so as not to oppose them. In 1914, the Black Hand ordered the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo that launched WWI.

In May 1902, Natalie converted to the Roman Catholic faith, and eventually became a lay sister in the Order of Notre Dame de Sion. As Alexander's sole heir, she donated everything he bequeathed to her to the University of Belgrade and to Serbian churches.

In December 1904 the London Chronicle announced Christie's sale of Queen Draga’s jewels and costumes, including her wedding dress, ‘made of white pleated satin, elaborately trimmed with fine old Brussels lace. A cabochon emerald and brilliant bracelet presented to Queen Draga on the occasion of her marriage by Tsar Nicholas. A brilliant tiara, worn at Her Majesty’s wedding, formed as a crest of ribbon and spray foliage, with two fine large brilliants in the centre, a Persian and Turkish order, and a gold pendant and a pair of earrings of Serbian design, set with pearls and diamonds which the Queen wore with the state costume.' The sale raised £2,335.00.

In the 1920’s, a New York Times reporter found Natalie at her home and asked the former queen as to why she had not written her memoirs. She replied: 'Memoirs require memories. I have forgotten everything in order to forgive everything.'

Milan died in Vienna in February 1901, aged 46, just six months before his son, while Nathalie lived until she was 81 and died in France in 1941.

More at the Esoteric Curiosa here

Anita Davison also writes as Anita Seymour, her 17th Century novel ‘Royalist Rebel’ was released by Pen and Sword Books, and she has two novels in The Woulfes of Loxsbeare series due for release in late 2014 from Books We Love. Her latest venture is an Edwardian cozy mystery being released next year by Robert Hale.

What a fascinating story.

ReplyDeleteOne thing always leads to another in history ;-)

ReplyDeleteWill this story be touched on in your next mystery?

Talk about "never a dull moment!" What fascinating stuff! Enjoyed it immensely and was almost breathless when finished reading.

ReplyDeleteThank you Elizabeth, Lisa and Donna - and Lisa you know me so well! Yes, this story is covered in my next cozy mystery, a little spying here some national activism there.....

ReplyDelete