by J.P. Reedman

The British bronze and Neolithic ages are much neglected eras where fiction is concerned. A few novels have been written about the building of Stonehenge, with varying degrees of success, but not many in comparison to, say, the later Iron Age. I believe this may in part be due to many writers (and readers) being unable to visualise what these people were like. We are used to Victorian and B-movie depictions of ‘Celts’ wearing blue woad and little else, and druids in pilfered bed sheets, but what about the people who preceded them by a millennium or two? Many people still seem to envision ‘cavemen,’ Bronze Age Fred Flintstones dragging megaliths. Over the years I have even seen archaeology books with drawings of ancient folk clad in jaunty ‘off the shoulder’ skins or, worse, building Stonehenge in the nude! (Ooh…painful!)

It couldn’t be further from the truth. By the early Bronze Age many tribes in Britain, especially around the Wessex area, had grown rather wealthy through trade and, perhaps, through the fame of their monuments. And they liked to show their wealth off, both to each other and to outsiders…

The earliest metalwork arrived in Britain around 2400-2300 B.C., brought by the ‘Beaker folk.’ For many years these people were thought to be violent ‘invaders’ due to their martial appearance—they had copper daggers, wore stern-looking stone archer’s wrist-guards, and shot lethal barbed arrows from composite bows—then it became fashionable to see their culture as spreading via trade rather than forcible imposition. Recent strontium isotope testing on Beaker skeletons has proved, however, that there was indeed a reasonable amount of migration from the continent. How these folk related to others already living in Briton is debatable; certainly most evidence for open warfare actually comes from a much earlier period of the Neolithic.

The most famous Beaker burial is the Amesbury Archer who was discovered about 3 miles from Stonehenge. A wealthy middle-aged man who had travelled from the Alps, he was probably a metal-worker—his whetstone had flecks of gold on its surface. In his grave, as part of a huge assemblage of prestige items including unprecedented amounts of archery equipment and two wrist-guards, were a pair of fine gold objects thought to be ‘hair tresses,’ denoting a high status. Another pair was discovered with a secondary burial that might have been his son or younger brother. Years before, in 1986, an almost identical burial had been found about 15 miles away near Andover, containing two more pairs of hair tresses of roughly the same date. In total about 8 pairs have been found across Britain, along with several single tresses. These hair-ornaments presumably had some special significance beyond mere ornamentation as they are all similar in design if not in size.

Weaving was known by the later Neolithic—a spindle whorl has turned up at Durrington walls—so rather than skins (which would mostly have been tanned rather than left furred, with exceptions being made for cloaks and bedding) people were beginning to wear woven clothes. Although very few textiles have survived from this era in Britain, the imprints of cloth, some patterned, has been discovered on bronze axes and other precious artifacts that had been wrapped before deposition in burial mounds. So garments doubtless had design, and probably were dyed with madder and other natural colourings.

Perhaps most extraordinary though is the jewellery and weaponry, showing long distance trade routes throughout Britain and beyond. By 1900 BC some form of ‘aristocracy’ was definitely appearing in southern England, though similar ‘Wessex style’ burials do appear in the east of England, Scotland, and Derbyshire’s Peak District (sometimes called an outpost of Wessex.) And they liked their ‘bling’!

Gold was common, imported from Wicklow, Ireland. The most famous find is the lozenge found in Bush Barrow, built within site of Stonehenge. It was found in the chest area of a 6 ft tall, strong, middle-aged man, who also had a small lozenge, a gold belt buckle, and a dagger imported from Brittany with a hilt studded with tiny gold pins, each as fine as a hair. He also had a ceremonial ‘mace’ with zigzag bone mounts and a polished head fashioned from a fossil.

He is not the only one to have such a kingly assemblage, although his hoard is the largest—Clandon barrow contained a similar lozenge only with a decagon pattern rather than a hexagon, and a mace-head made of shale fixed by large gold studs. A presumed female grave in Upton Lovell held a rectangular gold pectoral plate, gold-covered beads, conical gold buttons, and a crescent-shape necklace of hundreds of amber beads. Perhaps most stunning of all is the slightly later gold pectoral cape found in Mold, Wales; made to resemble draped cloth, it had loops at the bottom to attach a cloth gown. Other barrows had other rich goods—buttons etched with crosses and amber discs in decorated gold mounts, both probably representing the sun; other buttons were jet. There were necklaces of Dorset shale, Baltic amber, and Whitby jet. One burial had a rare, red glass bead—the only one ever found of its type. Occasionally there were copper or bronze bangles, engraved with patterns. Blue faience beads were produced, not Egyptian as once thought, but British-made…one very pretty piece was fashioned into a star. Belt rings of polished bone were worn, along with toggles for fastening clothes. Women’s pendants could resemble the ‘halberds’ or axes found in male graves, though at least one pendant is slightly macabre, perhaps an ancestral talisman…a shard of human skull covered by decorated gold.

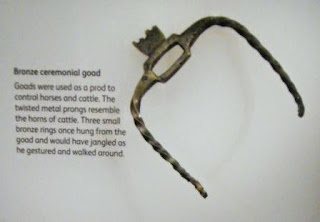

Weapons are common in male burials, as might be expected, although at least one grave opened by antiquarians was reported as being that of a ‘female hero’ (alas, we know little of the contents or what became of them) Daggers with riveted hilts of wood, horn or bone, flint knives, arrowheads and bronze axes were laid to rest with their owners; many showed signs of no use at all, so must have been prestige items for show rather than in daily use. A strange two-pronged metal implement was discovered in a mound not far from Stonehenge, perhaps some kind of ‘goad.’

A few barrows have unusual contents. One found at Upton Lovell covered the remains of a man known as ‘the shaman’. He had items in his tomb that could be termed archaic—the teeth of dogs and wolves which appear to have been sewn to his clothes, similar to items seen in the Mesolithic rather than the Bronze Age. Near him was placed a large ball of quartz which might have been a ‘seeing-stone.’ A similar designation of ‘magic man’ has been suggested for the very tall (over 6ft 3) man buried near the Torstone, Bulford. He possessed a strange quartz talisman shaped like a standing stone that may have been imported from outside Britain.

A recently discovered cist-burial of a young woman on Dartmoor is unique in that organics have in this instance survived, including parts of a possible shroud, a woven bag, a fringed nettle-fibre belt, and hand-turned wooden studs that were probably ear-plugs. Within her tomb was also a bracelet with a large tin bead and assorted studs, (the first tin ever found in British Bronze Age jewellery) and Baltic amber and shale.

So, clearly these prehistoric groups of Britain, trading within the Atlantic façade zone and elsewhere, were not backwards ‘poor cousins’ isolated at the edge of the known world by their island heritage. In the well-dressed, well-armed and well-decorated peoples of the British Bronze Age, we are seeing a heroic society forming that is the basis of the stories in the Welsh Mabinogion and the Irish Mythic Cycles.

Biobliography:

Britain Begins by Barry Cunliffe, OUP Oxford

Britain B.C. by Francis Prior, Harper Perennial

Celtic from the West, volumes 1 and 2, edited by Koch and Cunliffe, Oxbow Books

The Round Barrow in England by Paul Ashbee

*Most finds described above may be viewed at the Heritage Museum in Devizes, Wiltshire or at Salisbury Museum.

The British bronze and Neolithic ages are much neglected eras where fiction is concerned. A few novels have been written about the building of Stonehenge, with varying degrees of success, but not many in comparison to, say, the later Iron Age. I believe this may in part be due to many writers (and readers) being unable to visualise what these people were like. We are used to Victorian and B-movie depictions of ‘Celts’ wearing blue woad and little else, and druids in pilfered bed sheets, but what about the people who preceded them by a millennium or two? Many people still seem to envision ‘cavemen,’ Bronze Age Fred Flintstones dragging megaliths. Over the years I have even seen archaeology books with drawings of ancient folk clad in jaunty ‘off the shoulder’ skins or, worse, building Stonehenge in the nude! (Ooh…painful!)

It couldn’t be further from the truth. By the early Bronze Age many tribes in Britain, especially around the Wessex area, had grown rather wealthy through trade and, perhaps, through the fame of their monuments. And they liked to show their wealth off, both to each other and to outsiders…

The earliest metalwork arrived in Britain around 2400-2300 B.C., brought by the ‘Beaker folk.’ For many years these people were thought to be violent ‘invaders’ due to their martial appearance—they had copper daggers, wore stern-looking stone archer’s wrist-guards, and shot lethal barbed arrows from composite bows—then it became fashionable to see their culture as spreading via trade rather than forcible imposition. Recent strontium isotope testing on Beaker skeletons has proved, however, that there was indeed a reasonable amount of migration from the continent. How these folk related to others already living in Briton is debatable; certainly most evidence for open warfare actually comes from a much earlier period of the Neolithic.

The most famous Beaker burial is the Amesbury Archer who was discovered about 3 miles from Stonehenge. A wealthy middle-aged man who had travelled from the Alps, he was probably a metal-worker—his whetstone had flecks of gold on its surface. In his grave, as part of a huge assemblage of prestige items including unprecedented amounts of archery equipment and two wrist-guards, were a pair of fine gold objects thought to be ‘hair tresses,’ denoting a high status. Another pair was discovered with a secondary burial that might have been his son or younger brother. Years before, in 1986, an almost identical burial had been found about 15 miles away near Andover, containing two more pairs of hair tresses of roughly the same date. In total about 8 pairs have been found across Britain, along with several single tresses. These hair-ornaments presumably had some special significance beyond mere ornamentation as they are all similar in design if not in size.

|

| Replica of the Archer's hair tresses |

Perhaps most extraordinary though is the jewellery and weaponry, showing long distance trade routes throughout Britain and beyond. By 1900 BC some form of ‘aristocracy’ was definitely appearing in southern England, though similar ‘Wessex style’ burials do appear in the east of England, Scotland, and Derbyshire’s Peak District (sometimes called an outpost of Wessex.) And they liked their ‘bling’!

Gold was common, imported from Wicklow, Ireland. The most famous find is the lozenge found in Bush Barrow, built within site of Stonehenge. It was found in the chest area of a 6 ft tall, strong, middle-aged man, who also had a small lozenge, a gold belt buckle, and a dagger imported from Brittany with a hilt studded with tiny gold pins, each as fine as a hair. He also had a ceremonial ‘mace’ with zigzag bone mounts and a polished head fashioned from a fossil.

|

| Bush Barrow lozenge |

|

| Red glass bronze age bead |

|

| Bronze age goad |

A recently discovered cist-burial of a young woman on Dartmoor is unique in that organics have in this instance survived, including parts of a possible shroud, a woven bag, a fringed nettle-fibre belt, and hand-turned wooden studs that were probably ear-plugs. Within her tomb was also a bracelet with a large tin bead and assorted studs, (the first tin ever found in British Bronze Age jewellery) and Baltic amber and shale.

So, clearly these prehistoric groups of Britain, trading within the Atlantic façade zone and elsewhere, were not backwards ‘poor cousins’ isolated at the edge of the known world by their island heritage. In the well-dressed, well-armed and well-decorated peoples of the British Bronze Age, we are seeing a heroic society forming that is the basis of the stories in the Welsh Mabinogion and the Irish Mythic Cycles.

Biobliography:

Britain Begins by Barry Cunliffe, OUP Oxford

Britain B.C. by Francis Prior, Harper Perennial

Celtic from the West, volumes 1 and 2, edited by Koch and Cunliffe, Oxbow Books

The Round Barrow in England by Paul Ashbee

*Most finds described above may be viewed at the Heritage Museum in Devizes, Wiltshire or at Salisbury Museum.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

J.P. Reedman is the author of two novels set at the time of Stonehenge, Stone Lord and Moon Lord. In these books, the roots of the Arthurian legends are explored within a Bronze Age context. She lives in Amesbury, only a stone’s throw from the grave of the famous Amesbury Archer, and has a 30 year interest in Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures, specialising in burial and ritual.

J.P. Reedman is the author of two novels set at the time of Stonehenge, Stone Lord and Moon Lord. In these books, the roots of the Arthurian legends are explored within a Bronze Age context. She lives in Amesbury, only a stone’s throw from the grave of the famous Amesbury Archer, and has a 30 year interest in Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures, specialising in burial and ritual.

Have you seen Otzi the ice man? His back pack and clothes, his fire pot?

ReplyDeletePrimitive is not stupid.

I am hoping to see Otzi 'in person' one day. I love his cloak of woven grasses.

Delete(Not sure if I just posted this already). Interesting article, thanks!

ReplyDeleteIn terms of older stereotypes of the past, it is perhaps worth noting that human antiquity was only accepted in 1859 and that in the late 1860s respected antiquarians could insist that prior to the first Roman invasion of Britain the British Isles had been inhabited for at most a few generations. So the modern image of pre-Roman Britain that you conjure up is very recent indeed.

On a different note: I'm off to try to buy your first novel for my kindle. But you might consider changing the amazon.uk links for amazon.com - for someone outside the UK (such as myself) the former link does not work and I now have to search your books on the general site.

Just saw above:

ReplyDeleteStone Lord Amazon UK

Moon Lord Amazon UK

Stone Lord Amazon US

Moon Lord Amazon US

Hum. Either you just put them up, or I am an idiot. I suspect the latter. Apologies for pointless advice.