(Peers with Purpose, installment #1)

By John B. Campbell

Sir Samuel Hoare, 1st Viscount Templewood, and his wife Lady Maud Hoare, Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, Viscountess Templewood, demonstrated how to live a life of engagement and purpose. And they did so in the dramatic days of the early twentieth century.

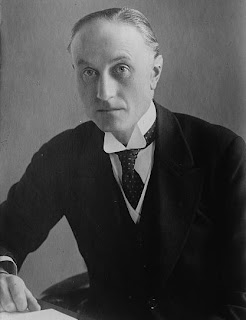

Samuel John Gurney Hoare, 1st Viscount Templewood, more commonly known as Sir Samuel Hoare, offset his relatively small stature with athleticism and dynamic (though not precisely charismatic) personality. Critics thought him to be narcissistically ambitious while others admired his drive, political savvy and concern for the greater good. The Machiavellian climate of the British government in those troubling days of anarchists, socialist campaigns, fascism and Nazi aggression created as much in-court-intrigue as that seen during the reign of Julius Caesar. Would Sir Samuel’s early years of training prove adequate?

In 1935, while Hoare served as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, a crisis arose when the Italians invaded Ethiopia. Hoare felt he understood the psyche of Benito Mussolini, whom he had gotten to know while previously serving with British overseas intelligence, and sensed diplomatic conflagration on the horizon. He thus felt the need to prevent the Italians from forming an alliance with the ever-menacing Adolf Hitler, were Anglo-Italian relations to become strained. In Hoare’s estimation, it seemed a good idea to join with Pierre Laval, the prime minister of France, in hopes of resolving the dilemma via a secret agreement. Their venture came to be known as the Hoare-Laval Pact and it outlined how Italy would be allotted two-thirds of the African territory it had conquered. In return, Ethiopia would be allowed to keep a narrow strip of territory with access to the sea. In those late days of The Empire, Hoare felt their solution was generous as well as prudent.

The details of the secret pact, however, mysteriously leaked to the press on December 10, 1935. The pact became widely denounced by the members of Parliament who sat in different camps from Hoare. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, being one such, rejected the plan and demanded Hoare’s resignation.

Sir Samuel Hoare’s resignation speech created one of those ‘moments’ film directors would love to recreate. Reportedly, Hoare stood up and presented a narrative so powerful it, in a flash, engendered a wave of sympathy. With sincerity and fervor, he told his story, explaining how by means of his negotiations “not a country, save our own, has moved a soldier, a ship or an aeroplane as a result.” Hoare was described by Henry Channon as a Cato defending himself, adding how Sir Samuel, for 40 minutes, had held the House breathless. When Sir Samuel sat down, however, he burst into tears.

From that account alone we glean a measure of the gentleman’s complexity of nature, his talents and vulnerability.

Earlier, Sir Samuel got his diplomatic feet wet in—talk about some colourful training—Czarist Russia. In 1916, he was assigned to a British intelligence team, comprising of Oswald Rayner, Cudbert Thornhill, John Scale and Stephen Alley. Leading them was Mansfield Cummings who had been appointed head of the British Secret Intelligence Service in Petrograd.

Sir Samuel Hoare, as I’d mentioned, was viewed by some as pompous. Whether it was pomposity or boldness, he served as the right kind of front man, from the right class, for Cummings’ purposes while the rest of the team worked behind the scenes, focusing their sights on the sinister clog to Russia’s international relations—Grigory Rasputin.

Hoare became friendly with Vladimir Purishkevich, the leader of the monarchists in the Duma, and in November of that year, he learned of the man’s interest in “liquidating” the “drunken debaucher influencing the Czarina and Russia’s policies.” Hoare later recorded that Purishkevich seemed so casual in his tone on the topic that such talk appeared as mere wishful thinking rather than an actual plot in motion.

At the end of 1916, after Purishkevich joined Prince Felix Yusupov, along with the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, they carried out their part in having the Tsarina’s special advisor killed.

Afterward, Hoare took issue with—of all people—Tsar Nicholas II (maybe Hoare was a bit pompous) who suggested a sole instigator behind the assassination: Hoare’s colleague, British agent Oswald Rayner. Whatever Hoare understood of the intrigue, he had had enough caviar and vodka and was grateful to leave the icy shark tank behind after getting reassigned to Rome.

Sir Samuel Hoare was literate and widely read in several languages, which had served him well in his demanding work in Russian and Italy during that early phase of his life. Later, timing served him well in that he was part of the wave of young Conservatives in 1922, which propelled him into increasingly senior Cabinet positions for the next 18 years, a bumpy ride, as we noted at the outset with the account of the Hoare-Laval Pact, but an all ‘round successful run.

Sir Samuel Hoare played a particular role that drew him to my attention while I was researching the era for my novel. As Foreign Secretary in 1935, he was instrumental in securing government approval for the British rescue effort on behalf of endangered Jewish children in Europe: Kindertransport.

It was in 1909 that Sir Samuel married Lady Maud Lygon, daughter of Frederick Lygon, 6th Earl Beauchamp. Her title took precedence over that of her husband until he was created a viscount in 1944.

Lady Maud intrigues me. I am still looking for more information on her. She earned her title, Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE), in the 1920s, as a result of being the first woman to fly a great distance—12,000 miles plus, as she inaugurated, along with her husband, the London-Cairo-Delhi air service.

You can watch a clip of the lady on the British Pathé site, which features a garden party she held for thalidomide children in or around 1963. Therein, fashionably dressed, she is down on her knees, interacting with the children.

Lady Maud traveled widely with her husband (at one point he was ambassador to Spain). She launched ships (the Ark Royal) and inaugurated airports (Croyden/London). This adventurous humanitarian peer makes a cameo appearance in my novel Walk to Paradise Garden.

Together, Sir Samuel and Lady Maud endeavored to make a marked difference in the world. How I’d love to time travel and be a guest at a dinner party with them. Wouldn’t you?

What an interesting post! And, yes, save me a seat at that dinner party. What fun! Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteWhat an amazing pair! I had read something of the Hoare-Laval pact, but had no idea how much was involved-your use of "Machiavellian" really describes it well. I, too, would like to join that party! Thank you.

ReplyDeleteinteresting..I hear he spent time in new zealand too

ReplyDelete