by Helena P. Schrader

Everyone familiar with the story of William Marshal knows that he was born the fourth son of John Marshal — and that at a very early age learned about his dispensability. When he was no more than five or six, his father not only gave him up as a hostage, he then broke his word, and added insult to injury by explicitly inviting his enemies to hang young William because he had the “hammer and anvil” to forge “betters sons.” So much for paternal love. Clearly, William Marshal was not born to destiny.

Everyone familiar with the story of William Marshal knows that he was born the fourth son of John Marshal — and that at a very early age learned about his dispensability. When he was no more than five or six, his father not only gave him up as a hostage, he then broke his word, and added insult to injury by explicitly inviting his enemies to hang young William because he had the “hammer and anvil” to forge “betters sons.” So much for paternal love. Clearly, William Marshal was not born to destiny.

Nor were his

first attempts at gaining fame and fortune auspicious. He famously fought so

valiantly in his first engagement that his horse was fatally wounded but he

failed to capture any hostages or booty.

He was forced to continue his search for fame and fortune on foot with

his arms tied to the back of an ass — it doesn’t get much more humiliating than

that in the 12th century world of chivalry. Of course, Marshal soon

won fame and booty at other tournaments, but the life of a “free lance” was not

only risky it was looked down upon. In the 12th century, every

knight who was not himself a land-holder or heir to lands (no matter how

humble) aspired to belong to a

household, i.e. to be retained and so have an assured income and a hearth at

which to eat and rest.

|

| Knight errantry was glamorized in 19th Century romances, but the reality was quite different. |

William Marshal,

after a short period proving himself on the tourney fields of France, returned

to England and applied for service with his maternal uncle, Patrick Earl of

Salisbury. He was welcomed into the Earl’s ménage, and it should have been a

comfortable and safe berth. If it had

been, we might never have heard of William Marshal, the faithful retainer of the

Earls of Salisbury. But a quirk incident was to earn him the attention — and

gratitude — of royalty.

It was in the

spring of 1168. The Earl of Salisbury was escorting Queen Eleanor of England to

Poitiers with a small escort including William Marshal. Suddenly the party was ambushed by “the

Lusignans.” The Lusignans had recently been dispossessed of their lands for

rebelling against Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine (and therefore her husband,

Henry II). They hoped by capturing Eleanor to gain a bargaining chip for the restoration

of their fortunes. The Earl of Salisbury turned over his own horse, which was

stronger and faster, to Eleanor so she could escape, but while he was

remounting he was fatally pierced from behind by a lance. William defended his

dying uncle with all the desperation of innocence lost until he too was

treacherously stabbed in the back of his thigh through the hedge he had backed

up against. He was taken captive and denied even bandages for his wounds; only

the kindness of a lady, who dared not openly help him but send him bandages in

secret, saved his life. Being of no value (as his father had drummed home when

he was six) and with his lord dead, William’s prospects were not good.

Fortunately for him, however, Eleanor of Aquitaine did not forget that Salisbury

and his nephew had prevented her capture. She ransomed William and so began his

rise — all the way to regent of England.

|

| One of my favorite allegorical images of a lady helping a knight in distress from the 15th century Le Livre de cuer d'amour espris by Renee d'Anjou. |

But who was the

rogue who stabbed an unarmed Earl in the back?

According to the

13th century biography of William Marshal, commissioned by his

eldest son and based on the accounts of many of Marshal’s contemporaries, this

ambush was led by Guy de Lusignan and his brother Geoffrey. Some sources claim

that Guy himself wielded the murderous lance.

And what became

of Guy de Lusignan? Allegedly, the

murder of Salisbury made Guy persona non grata in the courts of the

Plantagenets and induced him to seek his fortune in Outremer. Maybe, but there

was a gap of some 12 years, so maybe not. At all events, he arrived in

Jerusalem in late 1179 or early 1180 at the invitation of his elder brother

Aimery.

Aimery was making

a career in Jerusalem, according to some, by sleeping with the Queen Mother,

Agnes de Courtenay. At the time Guy arrived in the Holy Land, Baldwin IV was King — and clearly dying of leprosy. Since it was also clear that Baldwin IV

would not sire heirs of his body, his nephew Baldwin was his heir apparent.

|

| Seducing heiresses could be a very lucrative pastime. |

This boy had been

born to Baldwin IV’s elder sister Sibylla after the death of her first husband,

William of Montferrat. Sibylla herself was thus a young (20 year old) widow.

There were rumors, however, that she had pledged herself to the Baron of Ramla

and Mirabel. The rumors were widespread enough for Salah-ad-Din to demand a

king’s ransom (apparently in anticipation of Ramla becoming King of Jerusalem)

when Ramla was taken captive on the Litani in 1179 — and for the Byzantine

Emperor to pay that exorbitant ransom (that Ramla could not possibly pay from

his own resources) in anticipation of the same event.

But suddenly at

Easter of 1180, Sibylla married not Ramla (who was on his way back from

Constantinople) but the virtually unknown and landless Guy de Lusignan. The wedding was concluded in a hasty ceremony

lacking preparation and pomp. According to the most reliable contemporary

source, the Archbishop of Tyre (who was also Chancellor at the time and so an

“insider,”) Baldwin rushed his sister into the marriage with the obscure,

landless and discredited Guy because the Prince of Antioch, the Count of

Tripoli and the Baron of Ramla were planning to depose him and place Ramla on

the throne as Sibylla’s consort. Perhaps, but there is no other evidence of

Tripoli’s disloyalty, and Ramla’s hopes of marrying Sibylla had been known for

a long time — and all the way to Damascus and Constantinople. Why did that

marriage suddenly seem threatening to Baldwin VI?

|

| An illustration allegedly depicting a royal wedding in Jerusalem. |

Another

contemporary source, Ernoul, suggests another reason for the hasty and

unsuitable (for there is no way the third son of a Poitevin baron could be

considered a suitable match for a Princess of Jerusalem) marriage: that Guy had

seduced Sibylla. Aside from the fact that this had happened more than once in

history, the greatest evidence for a love match is Sibylla’s steadfast — almost

hysterical — attachment to Guy, as we shall see. Meanwhile, however, the marriage alienated

not only the jilted Baron of Ramla, but Tripoli as well. In short, it was not a

very wise move and so hard to explain as a political decision. Last but not least, even the Archbishop of

Tyre admits the King soon regretted his decision. All factors that point to

Ernoul’s explanation of a seduction, a scandal and an attempt to “put things

right” by a King who was devoted to his sister.

Guy was named

Count of Jaffa and Ascalon and appears to have been accepted by the Barons of

Jerusalem as a fait accompli that could no longer be changed — until, in

September 1183, Baldwin became so ill that he named his brother-in-law Regent. As such, Guy took command of the

Christian forces during Salah-ad-Din’s fourth invasion of the Kingdom. What

happened next is obscure. Yet something did

happen on this campaign because just two months later, when word reached

Jerusalem that the vital castle of Kerak was besieged by Saladin, the barons of

Jerusalem “unanimously” refused to follow Guy. King Baldwin had no choice but

to take back the reins of government and command of his army himself.

|

| The powerful border fortress of Kerak today |

As a footnote, it

was at about this time that William Marshal himself turned up in the Holy Land.

Henry the Young King had died in agony, begging William to fulfill his crusading

vow for him. William dutifully took Henry’s cloak with the cross on it and

travelled to the Holy Land. One wonders if he started talking to members of the

High Court about that incident with Guy de Lusignan so long ago? Certainly

Marshal had not forgotten or forgiven.

After Kerak had

been successfully relieved, Baldwin IV sought desperately to have his sister’s

marriage to Guy annulled. This had nothing to do with personal grievances

against Guy (although he had those too); it was necessary in order to find a

long-term solution to the succession crisis. His heir, his nephew, was a sickly

boy, and the kingdom needed a vigorous and militarily competent leader.

Baldwin’s efforts to replace the discredited Guy were thwarted by Sibylla, who staunchly refused to consider a divorce — something she is hardly likely to have done if

the marriage had been political in the first place.

Baldwin IV died

in 1185 and was succeed by his nephew with Raymond de Tripoli as Regent. The fact that Tripoli was made Regent — with

the consent of the High Court — and the Count of Edessa was made the boy's

guardian are both, again, indications of the intensity of the animosity and

suspicion the bishops and barons of Jerusalem had for Guy de Lusignan by this

time.

At the death of

Baldwin V roughly one year later hostility to Guy had not substantially

weakened. As was usual following the death of a king, the High Court was

convened to elect the next monarch. Some modern historians have made much of

the fact that Tripoli summoned the High Court to Nablus rather than convening it in Jerusalem itself. This is interpreted as a sign of disloyalty, but there is

nothing inherently disloyal about meeting in another city of the kingdom. High

Courts also met in Acre and Tyre at various times. Nablus was part of the royal domain,

comparatively close to Jerusalem, and the Templars under their new Master,

Gerard de Ridefort (surely the worst Master the Templars ever hand) were said

to have taken control of the gates and streets of Jerusalem. The Templars did

not have a seat in the High Court, but they controlled 300 knights and the

decision to hold the High Court in Nablus can just as easily been explained as

the desire to avoid “undue” influence from the Knights Templar.

In any case,

while the bulk of the High Court was meeting in Nablus, Sibylla persuaded the

Patriarch to crown her Queen in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. In addition to the Patriarch (allegedly

another former lover of her mother) and the Templars (whose Grand Master had a

personal feud with Tripoli), Sibylla was supported by her uncle Joscelyn Count

of Edessa and the colorful and controversial Reynald de Chatillon, Lord of

Oultrejourdan by right of his wife. We

know of no other supporters by name, but we know that Reynald de Chatillon sought

to increase Sibylla’s support by saying she would be Queen in her own right

without mentioning Guy. And even Bernard

Hamilton, one of Guy’s modern apologists, admits that: "Benjamin Kedar has

rightly drawn attention to sources independent of the Eracles[e.g. Ernoul] and

derived from informants on the whole favorable to Guy de Lusignan, which relate

that Sibyl's supporters in 1186 required her to divorce Guy before they

would agree to recognize her as queen.” (The

Leper King and His Heirs, Cambridge University Press, 2000 p. 218).

According to

these sources, Sibylla promised to divorce Guy and choose another man for her

husband as her consort. Instead, once she was crowned, she chose Guy as her

consort — and crowned him herself when the Patriarch refused. Once again, Sibylla had chosen Guy over not

only the wishes of her subjects but in violation of an oath/promise she had

made to her supporters (not her enemies note, to her supporters). I repeat: this is not the behavior of a woman who had

been forced in to a hasty and demeaning marriage by her brother out of

political expediency; it is consistent with a woman who was passionately in

love with the man who she had foisted upon her brother and her subjects against

their wishes.

|

| The coronation of Sibylla and Guy as depicted in Ridley Scott's Film "The Kingdom of Heaven" |

With this dual

coronation, Sibylla and Guy had usurped the throne of Jerusalem, but without

the Consent of the High Court they were just that — usurpers. The High Court (or rather those members of it

meeting at Nablus) was so outraged that, despite the acute risk posed by

Salah-ad-Din, they considered electing and crowning Sibylla’s half-sister

Isabella. To risk civil war when the country was effectively surrounded by a

powerful and united enemy is almost incomprehensible — and highlights just how

great the opposition to Guy de Lusignan was. In retrospect, it seems like madness

that men would even consider fighting their fellow Christians when the forces

of Islam were so powerful, threatening and well-led.

Then again, with

the benefit of hind-sight, maybe it would

have been better to dispose of Guy de Lusignan before he could lead the country

to utter ruin at Hattin?

In the event, Humphrey de Toron, Isabella’s young husband,

didn’t have the backbone to confront Guy de Lusignan, and so the baronial

opposition collapsed. Ramla, however, preferred

to quit the kingdom altogether rather than pay homage to Guy. He turned over his lucrative lordships to his

younger brother and went to seek his fortune in Antioch. Tripoli simply refused

to recognize Guy as his King and made a separate peace with Salah-ad-Din.

And there was one

other man who also refused to serve King Guy: William Marshal. Based on the fact that William joined the

Knights Templar on his deathbed, it is quite probable that he had been one of

many “lay” knights that joined the Templars on a temporary basis while in

Outremer. It would have been a perfect

means to do penance for the sins he had committed in Henry the Young King’s

service and still be the fighting man he was. Yet with Gerard de Ridefort’s

election to Grand Master and his decisive role in Guy’s coup d’etat, Marshal appears

to have been repulsed by Ridefort’s policies to the point where he left the

Templars and returned to the other end of the earth — despite the acute danger

the Holy Land was in.

Two months

latter, Guy de Lusignan proved that Ramla, Tripoli and the majority of the High

Court had rightly assessed his character, capabilities and suitability to rule.

Guy led the entire Christian army to an unnecessary but devastating defeat that led to the loss of the holiest city in Christendom, Jerusalem, and indeed the

entire kingdom save the city of Tyre. Only a new crusade would restore a

fragment of the Kingdom and enable Christendom to hang on to the coastline for

another century.

|

| The slaughter at Hattin from the film "The Kingdom of Heaven" |

And Guy? Guy was

taken captive at Hattin, but cravenly ordered the strategically important city

of Ascalon to surrender to Saladin to obtain his freedom. The garrison refused.

Saladin then let Guy go free a year later on a promise that he not take up arms against the Muslims

ever again, and Guy promptly broke his oath to lay siege to Acre. When Sibylla

and his daughters by her died, he refused to accept that his claim to the

throne was also dead and, with the backing of his father’s liege Richard the

Lionheart, clung to the title of “King” of the kingdom he had lost. After two years of trying to impose Guy on

the remaining fighting men of Jerusalem, even Richard the Lionheart

acknowledged it was pointless and dropped his support for Guy. But he offered a

consolation prize: the Island of Cyprus that Richard had conquered but could

not possibly control. In 1192, Guy went to Cyprus to try to subdue the

Byzantine subjects already up in arms because of the injustices suffered during

two years of Templar control of the island. He died there in 1194 to be

succeeded by his more competent elder brother, Aimery.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

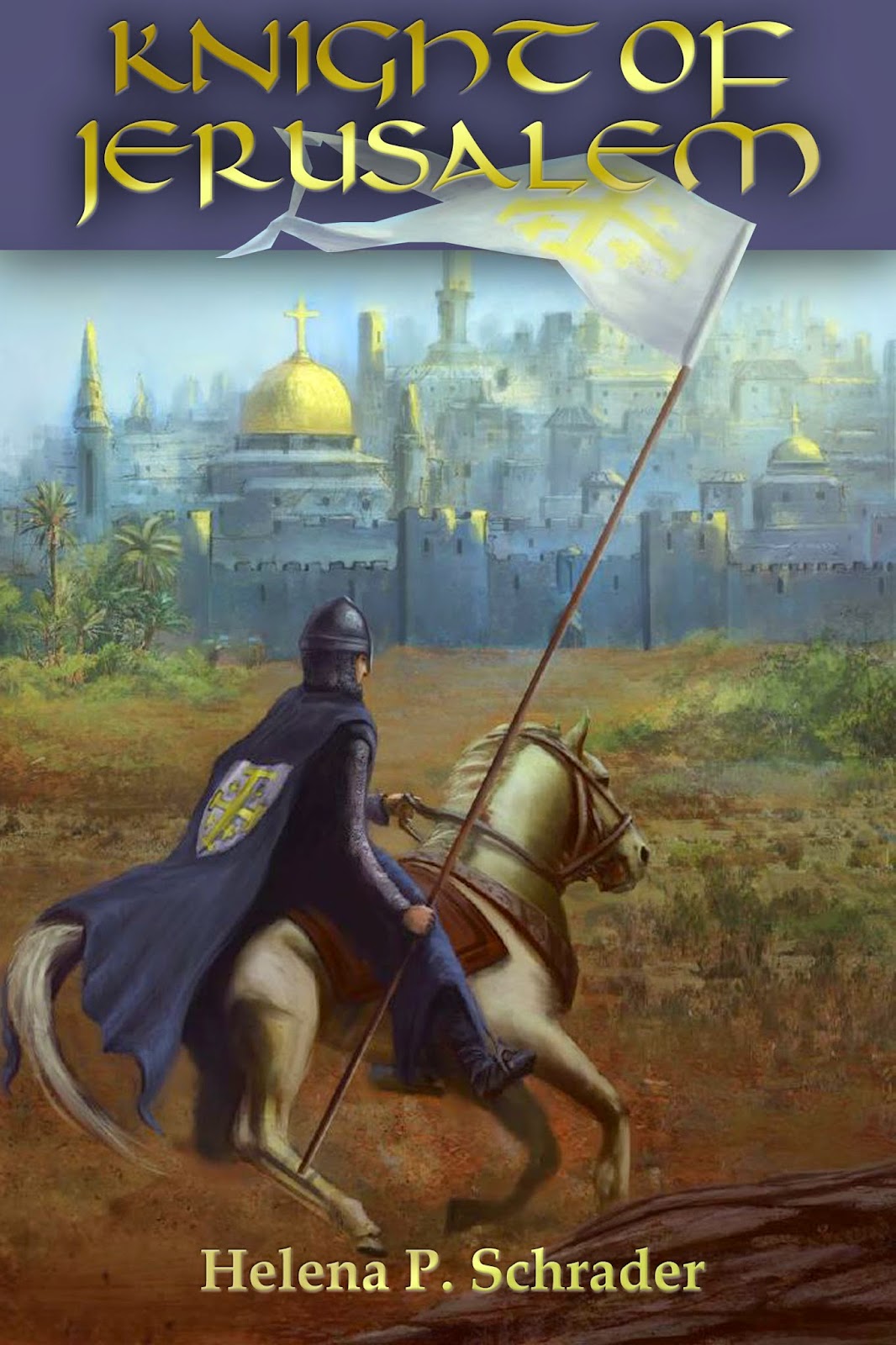

Helena P. Schrader is the

author of numerous works of history and historical fiction. She holds a

PhD in History from the University of Hamburg. The first book of a

three-part biographical novel of Balian d’Ibelin, who defended Jerusalem against

Saladin in 1187 and was later one of Richard I’s envoys to Saladin, is now

available for sale. Read more at: http://defenderofjerusalem.com,

http://helenapschrader.com or follow Helena’s blogs: Schrader’s Historical Fiction and Defending the Crusader Kingdoms.

http://helenapschrader.com or follow Helena’s blogs: Schrader’s Historical Fiction and Defending the Crusader Kingdoms.

Book I

A landless knight,

A leper King

And the struggle for Jerusalem.

The English Templar

The English Templar