|

| Elizabeth Raffald, From the 1782 edition of The Experienced English Housekeeper published by Baldwin |

She went into service at age 15, about 1748. She was familiar with and developed contacts in the city of York. There are indications that she worked for several families in Yorkshire. John Raffald, born around 1724, was from a family with market garden stalls in Manchester and that owned land where they grew plants in Stockport with links to Salford. (John was the oldest but signed his share over to his brother George.) John was working in Pontefract for a firm of nurserymen called Perfects of Pontefract, which sold plants. There are hints that Elizabeth may have worked for a family in Pontefract (in Yorkshire, less than 100 mi from York) at the same time. There is speculation that Elizabeth met John there. John was shown in employee records as head gardener at Arley Hall in Cheshire in January 1760 with earnings of 20 pounds per year (worth roughly $3822.85 US today*).

In December 1760, Elizabeth went to Arley Hall as housekeeper (Arley Hall records indicate that she came from Doncaster-it is unclear if it means that she travelled to Arley Hall from Doncaster or that her family was from that area), earning 16 pounds per year (worth roughly $3058.28 US today*). Arley Hall was owned by Sir Peter Warburton, 4th baronet, and his wife Lady Elizabeth. Her duties included managing the female servants, buying certain comestibles from travelling vendors and keeping accounts of the money spent (she received cash monthly, turned her accounts in to the steward monthly). She would have had duties in the kitchen as well, including making wine, pickling and preserving, baking special cakes, and making table decorations. She apparently developed an excellent relationship with Lady Elizabeth.

After serving three years as housekeeper, Elizabeth married John Raffald on March 3, 1763 at Great Budworth in Cheshire (a village near to and dependent on the Warburtons of Arley Hall). Because house rules did not allow married couples, Elizabeth and John had to leave. Arley Hall records show their marriage and that they both departed some weeks afterwards, in April 1763. Some sources indicate they were given a year’s salary at that time. The couple moved to Manchester were John’s family had two market stalls were they sold plants, vegetables and flowers. The Raffald family were an established family and ran market gardens near the market place, and also owned land near Stockport, a town roughly seven miles away. Sources indicate John went to work in his family’s business. This left Elizabeth to her own devices.

Manchester was a thriving market town, with a growing textile trade. There was a commodities market and warehouses for fabrics produced in the surrounding area. Money was being made, and there were those with ambitions to rise to the gentry class. From their home in Fennel Street, Elizabeth sold food products, including Yorkshire hams and other prepared foods, sweets, and “portable soup”, and rented out space in the cellar. She also made table decorations and catered dinners. In 1764, she established a Register Office where people could find servants seeking work.

Elizabeth and John moved to a location at Market Place (later number 12 Market Place) in August 1766, which was near the Bull’s Head Inn and the town center (convenient to the newspaper, the Exchange and the market where John and his brothers sold produce). She opened a confectioner’s shop, where she sold cakes and other sweets, tea, coffee, chocolate, and condiments. She also took orders for christening and bride cakes. In addition to these ventures, she taught cooking. She maintained her ties with Arley Hall, as receipts show purchases from her. Her wares expanded, including perfumes and other items. She and John took on the running of the Bull’s Head. Apparently, Elizabeth’s culinary skills paid off: the officers of military stationed in the area transferred their mess to the Bull’s Head.

During this time period, they also started their family. Daughter Sarah may have been born in January of 1765. Mr. Shipperbottom’s and Ms. Appleton’s research showed daughters as follows: Emma was born March of 1766, Grace November 1767, Betty January 1769, Anna (or Hannah) January of 1770 and Harriot (or Harriet) September of 1774. Another child Mary was born in February of 1771, with a male child who apparently did not survive. Although some sources indicate she had nine or even sixteen children, these seven daughters and one male child are the ones who are known.

In addition to caring for her family and her business enterprises, Elizabeth was also working on her cookbook. She dedicated it to Lady Elizabeth Warburton (whom she visited in 1766 and from whom she presumably got a blessing on the cookbook and its dedication) and included clear instructions for her recipes (numbering about eight hundred, and shown as her own), based on her experience and designed to be of benefit for novice cooks. She provided information on when what foods were in season, and how to set an elegant table (including diagrams). Interestingly, she did not include recipes for medicinals, a deliberate exclusion as she preferred to defer to “...the physician’s superior judgement, whose proper province they are.” (1)

|

| Foldout engraving of table layout for an elegant second course, from Elizabeth Raffald's The Experienced English Housekeeper, 4th Edition, 1775 |

The cookbook was published in 1769 on a local basis, by subscription. Eight hundred copies were sold in advance, and she signed the first page of each first edition. It was extremely popular and went into multiple editions. It is worth noting that in the second and later editions, new recipes were included that were not Elizabeth’s own. In another venture, Elizabeth gave Mr. Harrop of Harrop’s Manchester Mercury newspaper financial backing that allowed the paper to continue to be published. She entered into a similar venture in 1771 when she assisted in establishing Prescott’s Journal in Salford, a town near Stockport. She may have written articles for Prescott’s Journal. (Elizabeth had an appreciation for newspapers, as she advertised her wares in local periodicals on a regular basis.) Sometime between 1771-1773, she sold the copyright to Richard Baldwin of Paternoster Row in London for 1400 pounds (roughly $267,599.65 US today*).

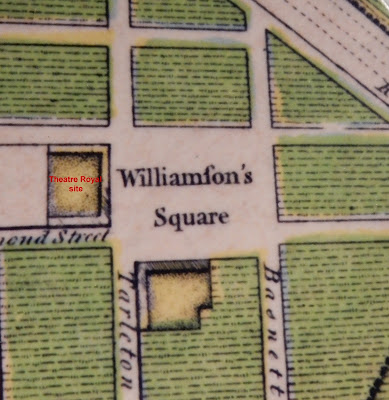

Also in 1772, she produced THE MANCHESTER DIRECTORY FOR THE YEAR 1772, a trade directory of 60 pages listing local businesses and inhabitants in alphabetical order and the first of its kind for the city of Manchester. She included the Raffalds but not herself in this directory. It was designed to benefit business people and customers alike by making it possible for them to discover the locations of businesses and residents alike. (It certainly was beneficial to her employees charged with deliveries.) She published new and updated editions in 1772, 1773 and 1781. Each edition was published in a limited run of one hundred copies.

In 1772, John and Elizabeth advertised that they were closing their respective businesses, and advertised on August 25, 1772 that they were taking over the King’s Head in Salford. The King’s Head was a coaching inn with accommodations (including meals), an assembly room and stables. They held entertainments, including cards and public dinners. The officers’ mess followed them from the Bull’s Head to the King’s Head. John was the host, and appears to have been the mastermind of the Florists’ Feasts. In 1774, Elizabeth went into partnership with a Mr. Swaine in hiring out carriages from the inn. Unfortunately, the carriage rentals were not successful.

At this point, there appears to be difficulties arising. John and Elizabeth were carrying a load of debt and John acquired a reputation for heavy drinking and inconsistent behaviour. There were problems with thefts. In spite of the income from her books, including the large lump sum from Mr. Baldwin, and encouragement of her sister Mary Whitaker who moved nearby in 1776 and opened her own confectioners shop, their debt load became excessive. They ended up having to assign all of their business effects to their creditors by December 1778 and leave the King’s Head.

Their next venture was the Exchange Coffee House, for which John received the license as master in October of 1779. The coffee house was a come-down from their previous establishment, and offered much less scope for Elizabeth’s talents as the food offerings were quite limited. Subsequently, she sold hot beverages and small treats from a stand to ladies and gentlemen at the Kersal Moor racecourse nearby in the summer of 1780. There are indications that she was co-author of a book on midwifery with physician Charles White during this period as well. The stand at Kersal Moor was apparently her last independent venture.

Elizabeth Raffald died suddenly, possibly of a stroke, April 19, 1781 aged approximately 48 years. She was buried in St. Mary’s churchyard, in Stockport, in a family vault belonging to the Raffald family. She was survived by John and three daughters, her youngest Anna and two of her four older girls (Grace is known to have died in March of 1770, but it is not clear whether Sarah, Emma or Betty died young). . Some accounts indicate she was buried in haste, as her name was not engraved on the stone. There is speculation that John simply could not afford to pay for the engraving. After her death, creditors closed in and John fled to London, where it is believed that he sold the manuscript of the midwifery book. He died in 1809 at the age of 85. He was buried in Salford.

Because of the fame of her cookbook, Elizabeth Raffald has been compared variously to Mrs. Beaton of Victorian Fame and today’s Mary Berry. However, because of her entrepreneurial spirit, head for business, and wide-ranging talents, I prefer a comparison to today’s Martha Stewart. Elizabeth not only cooked the food, she created table decorations and established guidelines for setting an elegant table. She branched out beyond cooking and her cookbook into other areas, including starting an employment register, publishing her Manchester Directories, running inns and leasing carriages. She was a fascinating woman. It is worth noting that, in 2013, some of her recipes were re-introduced at Arley Hall, when the general manager announced that her pea soup, lamb pie and rice pudding would be served in the hall’s restaurant. I think she would have been pleased.

* Currency converter: I used the converter using a base year of 1770 at this site: HERE

FOOTNOTES:

(1) Raffald, Elizabeth. THE EXPERIENCED ENGLISH HOUSEKEEPER. P. 3

Sources include:

Appleton, Suze. THE COMPLETE ELIZABETH RAFFALD Author, Innovator and More from Manchester’s 18th Century. 2017: Suze Appleton.

Raffald, Elizabeth. THE EXPERIENCED ENGLISH HOUSEKEEPER, with an Introduction by Roy Shipperton. Ann Bagnall, editor. 1997: Southover Press, Lewes.

Stephen, Sir Leslie, ed. DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY, Vol. 1-22, 1921-1922: Oxford University Press, London.

Arley Hall Archives. HERE

BBC.com “Georgian chef Elizabeth Raffald’s return to Arley Hall menu” posted April 6, 2013 (no author shown). HERE

Chesterfield Life. “Elizabeth Raffald-Arley Hall’s Domestic Goddess” by Paul Mackenzie, posted May 20, 2013 and updated Feb. 6, 2018. HERE

Museum of Fine Arts Houston. “Keeping House: The Story of Elizabeth Raffald” by Caroline Cole, posted Sept. 30, 2011. HERE

Sheroes of History. “Elizabeth Raffald: The Original Domestic Goddess and Celebrity Chef” by Naomi Wilcox-Lee, posted Dec. 10, 2015.HERE

The Elizabeth Raffald Society. HERE

Images:

Elizabeth, from the 1782 edition of THE EXPERIENCED HOUSEKEEPER, Wikimedia Commons (public domain). HERE

2nd Course Table Layout, from the 4th edition of THE EXPERIENCED HOUSEKEEPER, Wikimedia Commons (public domain). HERE

~~~~~~~~~~

Lauren Gilbert is a dedicated reader and student of English literature and history, holding a BA in liberal arts English with a minor in Art History. A long-time member of the Jane Austen Society of North America, she has done several presentations for the local region, and delivered a break out session at the 2011 Annual General Meeting. Her first book, HEYERWOOD: A Novel was published in 2011, and her second, A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT, will be released (finally!) later this year. She lives in Florida with her husband, and is researching material for a biography. For more information, visit her website here