“So great is said to have been the fervour of the faith of the Northumbrians and their longing for the washing of salvation, that once when Paulinus came to the king and queen in their royal palace at Yeavering, he spent thirty-six days there occupied in the task of catechizing and baptising.” (HE II 14*)The king in question is Edwin, seventh-century king of Northumbria, and the queen is his second wife, Æthelburg of Kent, known, according to Bede, by the nickname ‘Tate’.

Paulinus is said to have baptised people in the river Glen, which runs alongside the site of the palace. Visitors to the site will still be able to see the river, but of the palace, there is not a trace.

|

| The view across the site towards the river |

Archaeology has revealed that Yeavering at the time of Edwin’s reign was a magnificent royal vill. But Edwin didn’t build it. Rather, he rebuilt it.

What were Edwin, his wife, and the holy man Paulinus doing there? After all, it’s a forbidding place, surrounded by the towering Cheviot hills, windswept and desolate.

Edwin was technically the brother-in-law of the previous king of Northumbria, Æthelfrith, whose son, Oswald, was born to him by Edwin’s sister. Although in those days Northumbria was two distinct kingdoms, Deira (centred around York) and Bernicia (centred around Bamburgh), dynastic squabbles and bloody feuds meant that, periodically, one man ruled over both kingdoms.

|

| The English kingdoms c. 600 (Public Domain) |

In the seventh century, kings were gradually converting to Christianity. It was no quick decision, and usually had some political element to it. Edwin was not about to make a spur of the moment conversion. The site of Yeavering was significant because it was in an area previously ruled over by Edwin's nemesis, Æthelfrith. Would conversion bring more power?

Edwin evidently grasped what was expected of him, and offered a compromise – he expressed his willingness to convert if his advisers agreed, and undertook to place no obstacles in the way of missionary endeavour. He also offered a promise that took account of the position of Æthelburg, for he gave assurance that she and her retinue would be free to practice their own religion.

Paulinus, who travelled with ‘Tate’ from Kent, ‘bagged’ Edwin’s all-important royal soul, thus, according to Bede: when Edwin had been in exile in the court of Rædwald of East Anglia, an apparition came to him, promising him a kingdom, and salvation, if he would but remember by whose word this promise would be fulfilled. Paulinus now revealed himself now as the apparition by whose power Edwin had gained his kingdom. (HE II 12)

When the king and queen had produced a daughter, Eanflæd, Edwin was persuaded to allow Paulinus to baptise her in thanksgiving for his wife’s safe delivery.

Yeavering lies in what was the kingdom of Bernicia, forty miles north of Hadrian’s Wall, and about twenty miles inland from the great fortress of Bamburgh. It is a desolate and often a very cold place. Bede describes it as a royal vill, (town) and talks about the work of Paulinus there, but he also tells us that at some time later it was abandoned. Perhaps the archaeology and the history can be linked?

|

| The site, showing the modern wall at the roadside |

In 1949 an aerial photograph showed the marks of extensive buildings there, and the site was then excavated by Dr Hope Taylor.

He found that as a place of burial, Yeavering had a long prehistoric past. A big and seemingly elaborately defended cattle corral is likely to have gone back to the days when the area was ruled by British, not English, kings. Hope Taylor also discovered a series of buildings dating from the end of the sixth century to somewhat later than the middle of the seventh, corresponding to the reigns of Æthelfrith, Edwin, and Oswald.

Among the most important were a succession of halls. The largest, which he concluded was probably Edwin’s, was over 80 feet long and nearly 40 feet wide. Its walls were likely made of planks, 5 ½ inches thick. The fact that the post holes showed that timber were set up to eight feet into the ground, suggests that the walls must have been very high. There may have been a clerestory (a high section of wall that contains windows above eye level, with the purpose of letting in light, and/or fresh air). Its successor, probably dating to the reign of Oswald, Edwin’s nephew and successor, was equally grand.

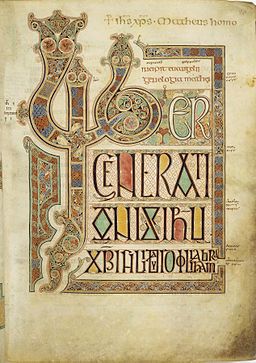

|

| Yeavering - digital 'fair use' image. (Attribution) |

More remarkable still was a kind of grandstand, (top left of above image) shaped like a segment of a Roman amphitheatre, which stood facing a platform. When first built, possibly under Æthelfrith, it had accommodated about 150 people; later, perhaps under Edwin, it was enlarged to hold about 320.

It has been agreed that its only purpose can have been for meetings; and of a kind where one man on the platform, presumably the king, faced many. Perhaps it was here that Edwin consulted his amici, principes and consiliarii on the adoption of Christianity (though this debate more probably took place in York, where Edwin finally received his baptism.)

Yeavering in its heyday would have stood as a symbol of the might and power of Edwin, who, as one of the named ‘bretwaldas’ (overkings) in Bede’s list, wielded considerable power. A prince of Deira, he would have known the importance of establishing his authority across Bernicia, and building over the remnants of his predecessor’s hall.

And yet, the royal buildings at Yeavering were not fortified. Perhaps they should have been; there is evidence that the palace was destroyed by fire, not once, but twice, and the dates coincide with Bede’s records of Mercian incursions into Northumbria.

Additional finds included what may have been a pagan temple later converted to Christian use, and a building which might have been a small Christian church.

Yeavering, though a major centre for Bernicia, was by no means the only such centre these kings possessed. There was another, much more important, at Bamburgh, and other royal vills scattered through their kingdom, many of which may have had halls as grand. But the wonderful thing, for historians, is that we have the evidence for this one, even though there is now no trace of these once impressive and imposing buildings. To stand in this enormous field, (and it is a huge site) gazing out over the waters of the river Glen, and know that here stood the people whose lives I have studied, and written about, for years was, even on that very cold and blustery day, really quite moving. So little of Anglo-Saxon architecture remains, but thanks to Dr Hope Taylor, and to Bede, at least we know what once was here.

As to why it was, as Bede tells us, abandoned, well that remains a mystery, and one which neither the archaeology (which suggests 655, a time of Northumbrian supremacy) nor the history seem able to solve.

[*Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People]

~~~~~~~~~~

Annie Whitehead is an author and member of The Royal Historical Society. Her novels are all set in Anglo-Saxon Mercia and her latest, Cometh the Hour, includes the character of King Edwin, who was at turns related to, and then at war with the mighty pagan king, Penda.

Cometh the Hour

Amazon Author Page

Blog

Website