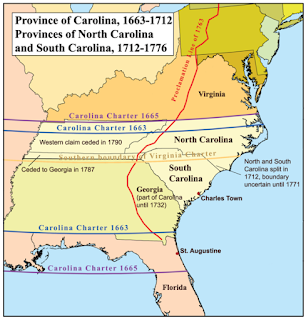

Before there was a North and South Carolina, there was the province of Carolina. The Englishmen who oversaw this vast wilderness in the American colonies were known as the Lords Proprietors. King Charles II provided these eight men of noble blood with a charter to establish a colony there.

The Proprietors were George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (pictured above), Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, John Berkeley, 1st Baron Berkeley of Stratton, William Craven, 1st Earl of Craven, Sir George Carteret, Sir William Berkeley, Sir John Colleton, 1st Baronet, and Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury. The Duke of Albemarle’s name was used for Albemarle Point, where Charles Town (modern day Charleston) was first settled. Anthony Ashley Cooper’s name would provide the names of Charleston’s two large, flanking rivers—the Ashley and the Cooper. Each of these men contributed at least £775 sterling, not a small amount in the late seventeenth century, for their Carolina endeavor. These men had “extensive experience at the leading edge of early modern commerce.”

|

| Anthony Ashley Cooper |

In S. Max Edelson’s book Plantation Enterprise in Colonial South Carolina, the author also writes, “The colony’s Proprietors exercised their legal title to Carolina as if the scope of their official authority conveyed the power to implement their schemes for settlement, society, and production. Their dilated visions of exotic commodities, new-world aristocrats, and village communities failed to appreciate how little settlers wished to be subjects.”

The Proprietors envisioned the lowcountry of Carolina as some sort of utopia where a new aristocracy would arise and rule over settlements and farms grouped together. To urge settlers to come to this new world they spread word of fertile soil and wonderful climate, as well as religious freedom. This latter promise enticed some, like the French Huguenots, to come there. The majority of settlers, however, were Englishmen from Barbados where land was becoming scarce due to the sugar plantations there.

The Proprietors had a wide range of ideas on how to make Carolina prosperous and lucrative, most based around agriculture. Silk and wine were two of the ideas nurtured, and commodities like corn thrived. One of the Proprietors’ experimental plantations toyed with growing cotton, ginger, olives, indigo, and sugarcane. The crop that eventually made the colony rich was rice, which thrived in the lowcountry’s flat, marshy land, where rivers, not roads, were thoroughfares in the vast wilderness.

|

| Image attribution LINK |

Fifty acres were granted to colonists as well as fifty acres for each free and enslaved dependent. For a small charge, additional acres could be bought, turning a small farm into large landholdings. From these acquisitions, the Proprietors collected quitrents. By 1680, ten years after the start of the colony, about 1,000 white settlers lived in South Carolina. This number would rise to around 6,000 by the end of the century.

Colonists from Barbados accounted for between 300 and 400 of those early settlers. They arrived from a well-established plantation community where shortages of fresh water and arable land made the pull of a new life and opportunity in the Proprietors’ Carolina irresistible. These experienced planters brought their slaves with them and had them planting many of the crops that flourished in the Caribbean—sugarcane, ginger, yams, tobacco, and indigo. In turn, they supplied Barbados with many of the resources it lacked—wood and meat, among other things.

These settlers’ wealthy elites would lead the colony’s revolt against of Proprietary reign. The first thing they did was reject Ashley’s designs of keeping settlers grouped together. The very topography of the land worked against this design—swamps and marshes stretched everywhere, making it impossible to ensure large swaths of arable acreage. So these experienced planters looked for better land, often finding that further inland from settlements like Charles Town, spreading out in resistance to the Proprietors’ scheme of community cohesion.

These colonists “rejected the view of Carolina as a vast plantation in which they were subjects [of the Proprietors]. Instead, they defined the plantation as an independently owned tract in which possession conveyed the power to command people and resources within its boundaries.” This removed them from the hierarchal society Ashley had hoped to engrain and made them into “propertied men who ruled independent domains.” The plantation aristocracy would eventually arise from ranks that had not been envisioned by the Proprietors.

Before rice took root as the driving crop in Carolina in the 1690s, these English planters made money from a familiar source—cattle. “As grossly distorted as Carolina’s version of mixed English farming might appear to agricultural improvers, subsistence-oriented grain production, combined with livestock raising for the market, formed the backbone of the new colony’s economy as it had structured the English rural economy for the better part of two centuries.”

Some historians credit the Proprietors with introducing rice to Carolina. However, its origin more likely should be credited to the enslaved Africans who toiled in the colony. Many of these slaves came from regions of Africa where rice was grown and eaten daily. While these slaves couldn’t have imported the seeds themselves, they certainly had more innate knowledge of cultivating it than their English masters. How such seeds arrived is left to legend, with various stories told.

As the Barbadian planters grew in power, they dominated the Commons House of Assembly and eventually were able to end Proprietary rule in 1719. No doubt their burgeoning power came from the growing value of rice as an exported commodity and the Proprietors’ continued frustration with their economic and social experiment not going according to plan, stymied by independent-thinking settlers. King George I converted the colony’s status to that of a royal colony.

“Planters did not reject the projecting vision for Carolina’s development outright, but as they managed independent plantations, they ignored its goals and left open-ended the ultimate social and economic product of their individual enterprises,” Edelson writes. This independent spirit in the American colonies would eventually lead to its struggle to break from England.

[all images in the Pubic Domain unless otherwise stated]

~~~~~~~~~~

When Susan Keogh won an elementary school writing contest and a trip to a regional young writers conference, she hadn’t realized that experience was the beginning of a love affair with words. Keogh was raised in a large family where reading was encouraged. Through her mother’s interest in history, Keogh grew to admire such authors as Michael Shaara and Bruce Catton, a fellow Michigan writer who focused on the American Civil War. So it was no wonder that her first writing credit was a featured article in the magazine America’s Civil War.

Keogh’s most recent time period of historical interest is early colonial America. She has crafted a series of novels that center around the adventures of Jack Mallory, a young Englishmen who is both pirate and eventually the patriarch of a large rice plantation in the colonial province of Carolina.

I assume these Dukes and Earls didn’t actually live there? Or did they?

ReplyDeleteLord Cooper was physically in Charleston (at that time, Charles Town) to oversee Carolina's early years. It was not, as far as I know, a permanent move.

ReplyDeleteHis descendants are still considered noblity. His great (×10) grandson is Nicholas Ashley Cooper, the 12th Earl of Shaftsbury. The DNA in that family is pretty strong, as their facial features are almost identical.