By Lauren Gilbert

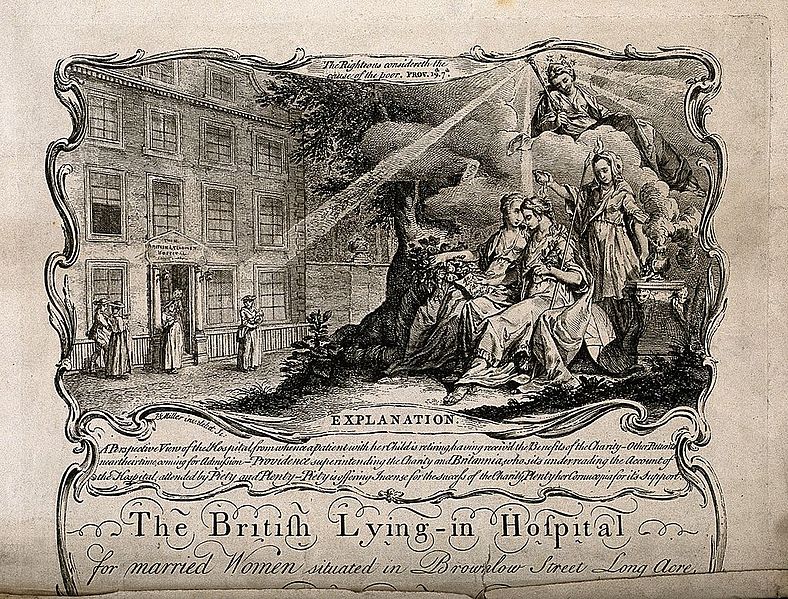

Specialised health care seems such a modern concept. When we read about medicine in the past, many things seem primitive and downright frightening. An especially vulnerable population is that of pregnant women. Midwives are the primary caregivers that come to mind. Generally one imagines a woman during the Georgian era giving birth at home, surrounded by female relatives under the guidance of a midwife. Although childbirth was considered a female issue, women of wealth and position were often under the care of an accoucher (a doctor trained in obstetrics or a male midwife). Princess Charlotte the daughter of the Prince of Wales during the Regency (later George IV) was under the care of society doctor Sir Richard Croft (there was a very sad outcome but that is for another article by Regina Jeffers HERE). What about women who did not have the money, the female relatives or even the home for her labour? The British Lying-in Hospital for Married Women provided an answer for some. The British Lying-In Hospital for Married Women on Brownlow St. in Long Acre was not the first established but it was the first to come to my attention.

The first hospital of this kind was opened in Dublin in March of 1745 by Dr. Bartholomew Mosse. He purchased the property and initially supported it himself. As the hospital’s work came to public awareness and its usefulness acknowledged, subscribers came forward to help with costs. Dr. Mosse also initiated plays, musicales, and other events from whose proceeds the hospital also derived revenue. An added advantage to providing care for women in need was the opportunity for young surgeons to learn midwifery locally. After reports were made, Dr. Mosse was requested to open a similar hospital in London in 1747. It was so successful, two more were opened before 1751. One of these was the lying-in hospital on Brownlow Street in Long Acre.

The Lying-in Hospital for Married Women in Holborn was founded in November 1749. As with the others, this lying-in hospital was funded with subscriptions and donations. A property was purchased on Brownlow Street in Long Acre and furnished with 20 beds. It was to be staffed with 2 physicians and 2 surgeons, all of whom trained in midwifery, a chaplain, and an apothecary. Also on staff was a Matron who was a trained midwife, nurses and other servants as needed. Women who were accepted were admitted in the last month of pregnancy. When labour began, the matron would send for the physician or surgeon on duty who would determine if his services were needed or if delivery could be handled by the matron. Patients for whom an easy delivery was expected were left in the matron’s care. No money was to be received for these services.

This hospital did not accept all women approaching delivery. The rules for admission were quite strict. An applicant had to provide a letter of recommendation from a subscriber, an affidavit of marriage, and an affidavit of settlements made by the husband. As time went on, the applicant was also required to present testimonials of her poverty with statement from two householders who could vouch for her circumstances to alleviate any doubt the hospital board may have regarding her poverty. This documentation could be presented as much as 3 months in advance, allowing the applicant to be put on an admissions list. (If she did not come in to be admitted within the 3 months, she was struck off and had to start over again when it was time.) When being admitted, she must be clean and free of vermin, and bring with her any clothing needed for herself and for her child. If she was insane, she could not be admitted unless a guarantor would accept responsibility.

If a woman lied about her circumstances or otherwise tried to gain admission under false pretences, her name was entered into a Black Book and she would never been eligible for admission to the Lying-in Hospital. In 1751, a woman name Anne Poole lied about being married and claimed she had been deserted. When her lie was caught, she was ejected from the hospital. (In 1759, an attempt was made to allow admission of single women but it was not successful.) An admitted patient could be in the hospital 3 weeks (longer if medically necessary) and would receive 3 meals per day. There were even 3 levels of diet: low (lots of broth), regular (fairly well balanced) and high (a lot of extra meat), depending on the perceived medical needs of the patient.

Once admitted, the rules of visitation were strict. There were no visitors allowed on Sundays until after religious services had ended. Women who had not yet been delivered of their children could only receive visitors in the hall unless special permission had been obtained from the matron or one of the gentlemen in charge. A woman who had delivered was allowed no visitors for one week after the birth of the child, unless special permission was obtained. Visiting hours were from 3:00 to 7:00 from Lady-Day to Michaelmas (roughly April to September or spring/summer), and from 2:00-4:00 from Michaelmas to Lady-Day (late September to April or autumn/winter). No men (including husbands) were allowed to visit in the wards. Children born in the hospital were baptised by the chaplain; baptisms were held every Thursday. If a patient or her child(ren) died, the matron was responsible for notifying the patient’s family to come and get the remains for burial. If no one responded, the matron would make arrangements at the lowest cost possible. When a patient left (by discharge or death), the hospital’s secretary would notify the individual who recommended that patient that a vacancy was available.

Almost immediately, more beds were needed. Extra beds were added whereever possible, and they tried to find lodgings for women awaiting delivery. Availability became so limited that in 1755, admissions were selected by a ballot involving black and white balls: white balls in the number of available spaces, and sufficient black balls to make up the total number of applicants. Each applicant then drew; if a white ball were drawn, that woman gained admission. If a black ball were drawn, that person could not be admitted. They gave up this practice in 1800, after which time anyone subscribing 3 guineas could nominate a patient. (3 guineas in 1800 would have paid the wages of a skilled tradesman for 21 days in 1800.)

Starting in 1752, female pupils were admitted for 6-month terms to study midwifery. They paid 10 shillings for board and lodging, and 20 guineas for instruction. They were instructed in general and difficult childbirths, and (when they completed the program) were given a certificate. A general meeting was held quarterly to review the hospital’s rules. At these meetings, 15 governors were selected to form a committee to meet weekly to receive the patients and direct the hospital. Medical records appear to be lacking for the hospital. However, it appears that a report was issued in 1751, which indicates that 545 woman were delivered of 550 babies with 29 stillbirths*. There were also reports issued every ten years regarding infant deaths: the statistics generated from these reports shown indicate that there were 71 perinatal deaths (deaths that occur in the period within 3 months before to 3 months after birth) per thousand between 1749-1796.* No discussion of medical conditions for women who have had birth is complete without considering puerperal fever (an infection in women who have given birth), and the lying-in hospital was not immune to this condition. According to Essays on puerperal fever and other diseases peculiar to women, p. 6, 24 women died of puerperal fever between June 12, 1760 and late December, 1760 at the British Lying-in Hospital for Married Women. (In 1756, the hospital was re-named the British Lying-in Hospital for Married Women, to avoid confusion with other lying-in hospitals in London, which allows us to identify this statistic as relating particularly to this hospital.)

The hospital continued offering services throughout the Georgian era. Fundraisers were held, including plays. Productions of plays for this cause resulted in David Garrick and James Lacey Esq. being named perpetual governors in 1758 in recognition of their efforts. In 1820, the Duke of Wellington became a vice-president. Others in the nobility became donors or subscribers. In 1828, it began sending midwives to patients’ homes to deliver their babies. In 1840, in Victoria’s reign, the Brownlow Street location was condemned, and the hospital was rebuilt on Edell Street. The new hospital had 40 beds. No regular medical reports were generated until 1870 (other than the 10 year summaries already mentioned). Over time, the hospital developed financial difficulties and gradually deteriorated (the building was in poor repair, the neighbourhood population was declining and the newer teaching hospitals had opened maternity wards). The British Lying-in Hospital for Married Women finally closed in 1913. The buildings were sold, and the funds raised were used with other monies to build special facilities for the British Hospital for Mothers and Babies in Woolwich.

*Statistics from Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine Journals cited below.

GoogleBooks. Essays on the puerperal fever and other diseases peculiar to women. Edited by Fleetwood Churchill, M.D., M.R.I.A. London: Sydenham Society, 1849.HERE

GoogleBooks. THE DUBLIN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCE, VOL. 2. “The Memoirs of Dr. Mosse” (pages 565-596) Dublin: Hodges & Smith, 1816. HERE

Lost Hospitals of London. “British Lying-in Hospital”. (No date or author of post shown.) HERE

The National Archives. “The British Lying-in Hospital” (see Administrative/biographical background). HERE

Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine Journals. Volume 65, May 1972. (PDF) “The Lying-in Hospital 1747-“ by C. Keith Vartan, FR CGOG HERE

NCBI. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. “British maternal mortality in the 19th and carly 20th Centuries” by Geoffrey Champerlain. Nov. 2006. Vol. 99 (11): 559-563. HERE

Illustration from Wikimedia Commons: HERE

Lauren Gilbert is the author of HEYERWOOD: A Novel, and is in the process of completing her second novel, A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT. She lives in Florida with her husband. She will be attending the Tampa Indeie Author Book Convention next month. Visit her website here for more information.

|

Attribution: Wellcome

Collection gallery (2018-04-03): https://wellcomecollection.org/works/yhnmeumy CC-BY-4.0

|

Specialised health care seems such a modern concept. When we read about medicine in the past, many things seem primitive and downright frightening. An especially vulnerable population is that of pregnant women. Midwives are the primary caregivers that come to mind. Generally one imagines a woman during the Georgian era giving birth at home, surrounded by female relatives under the guidance of a midwife. Although childbirth was considered a female issue, women of wealth and position were often under the care of an accoucher (a doctor trained in obstetrics or a male midwife). Princess Charlotte the daughter of the Prince of Wales during the Regency (later George IV) was under the care of society doctor Sir Richard Croft (there was a very sad outcome but that is for another article by Regina Jeffers HERE). What about women who did not have the money, the female relatives or even the home for her labour? The British Lying-in Hospital for Married Women provided an answer for some. The British Lying-In Hospital for Married Women on Brownlow St. in Long Acre was not the first established but it was the first to come to my attention.

The first hospital of this kind was opened in Dublin in March of 1745 by Dr. Bartholomew Mosse. He purchased the property and initially supported it himself. As the hospital’s work came to public awareness and its usefulness acknowledged, subscribers came forward to help with costs. Dr. Mosse also initiated plays, musicales, and other events from whose proceeds the hospital also derived revenue. An added advantage to providing care for women in need was the opportunity for young surgeons to learn midwifery locally. After reports were made, Dr. Mosse was requested to open a similar hospital in London in 1747. It was so successful, two more were opened before 1751. One of these was the lying-in hospital on Brownlow Street in Long Acre.

The Lying-in Hospital for Married Women in Holborn was founded in November 1749. As with the others, this lying-in hospital was funded with subscriptions and donations. A property was purchased on Brownlow Street in Long Acre and furnished with 20 beds. It was to be staffed with 2 physicians and 2 surgeons, all of whom trained in midwifery, a chaplain, and an apothecary. Also on staff was a Matron who was a trained midwife, nurses and other servants as needed. Women who were accepted were admitted in the last month of pregnancy. When labour began, the matron would send for the physician or surgeon on duty who would determine if his services were needed or if delivery could be handled by the matron. Patients for whom an easy delivery was expected were left in the matron’s care. No money was to be received for these services.

This hospital did not accept all women approaching delivery. The rules for admission were quite strict. An applicant had to provide a letter of recommendation from a subscriber, an affidavit of marriage, and an affidavit of settlements made by the husband. As time went on, the applicant was also required to present testimonials of her poverty with statement from two householders who could vouch for her circumstances to alleviate any doubt the hospital board may have regarding her poverty. This documentation could be presented as much as 3 months in advance, allowing the applicant to be put on an admissions list. (If she did not come in to be admitted within the 3 months, she was struck off and had to start over again when it was time.) When being admitted, she must be clean and free of vermin, and bring with her any clothing needed for herself and for her child. If she was insane, she could not be admitted unless a guarantor would accept responsibility.

If a woman lied about her circumstances or otherwise tried to gain admission under false pretences, her name was entered into a Black Book and she would never been eligible for admission to the Lying-in Hospital. In 1751, a woman name Anne Poole lied about being married and claimed she had been deserted. When her lie was caught, she was ejected from the hospital. (In 1759, an attempt was made to allow admission of single women but it was not successful.) An admitted patient could be in the hospital 3 weeks (longer if medically necessary) and would receive 3 meals per day. There were even 3 levels of diet: low (lots of broth), regular (fairly well balanced) and high (a lot of extra meat), depending on the perceived medical needs of the patient.

Once admitted, the rules of visitation were strict. There were no visitors allowed on Sundays until after religious services had ended. Women who had not yet been delivered of their children could only receive visitors in the hall unless special permission had been obtained from the matron or one of the gentlemen in charge. A woman who had delivered was allowed no visitors for one week after the birth of the child, unless special permission was obtained. Visiting hours were from 3:00 to 7:00 from Lady-Day to Michaelmas (roughly April to September or spring/summer), and from 2:00-4:00 from Michaelmas to Lady-Day (late September to April or autumn/winter). No men (including husbands) were allowed to visit in the wards. Children born in the hospital were baptised by the chaplain; baptisms were held every Thursday. If a patient or her child(ren) died, the matron was responsible for notifying the patient’s family to come and get the remains for burial. If no one responded, the matron would make arrangements at the lowest cost possible. When a patient left (by discharge or death), the hospital’s secretary would notify the individual who recommended that patient that a vacancy was available.

Almost immediately, more beds were needed. Extra beds were added whereever possible, and they tried to find lodgings for women awaiting delivery. Availability became so limited that in 1755, admissions were selected by a ballot involving black and white balls: white balls in the number of available spaces, and sufficient black balls to make up the total number of applicants. Each applicant then drew; if a white ball were drawn, that woman gained admission. If a black ball were drawn, that person could not be admitted. They gave up this practice in 1800, after which time anyone subscribing 3 guineas could nominate a patient. (3 guineas in 1800 would have paid the wages of a skilled tradesman for 21 days in 1800.)

Starting in 1752, female pupils were admitted for 6-month terms to study midwifery. They paid 10 shillings for board and lodging, and 20 guineas for instruction. They were instructed in general and difficult childbirths, and (when they completed the program) were given a certificate. A general meeting was held quarterly to review the hospital’s rules. At these meetings, 15 governors were selected to form a committee to meet weekly to receive the patients and direct the hospital. Medical records appear to be lacking for the hospital. However, it appears that a report was issued in 1751, which indicates that 545 woman were delivered of 550 babies with 29 stillbirths*. There were also reports issued every ten years regarding infant deaths: the statistics generated from these reports shown indicate that there were 71 perinatal deaths (deaths that occur in the period within 3 months before to 3 months after birth) per thousand between 1749-1796.* No discussion of medical conditions for women who have had birth is complete without considering puerperal fever (an infection in women who have given birth), and the lying-in hospital was not immune to this condition. According to Essays on puerperal fever and other diseases peculiar to women, p. 6, 24 women died of puerperal fever between June 12, 1760 and late December, 1760 at the British Lying-in Hospital for Married Women. (In 1756, the hospital was re-named the British Lying-in Hospital for Married Women, to avoid confusion with other lying-in hospitals in London, which allows us to identify this statistic as relating particularly to this hospital.)

The hospital continued offering services throughout the Georgian era. Fundraisers were held, including plays. Productions of plays for this cause resulted in David Garrick and James Lacey Esq. being named perpetual governors in 1758 in recognition of their efforts. In 1820, the Duke of Wellington became a vice-president. Others in the nobility became donors or subscribers. In 1828, it began sending midwives to patients’ homes to deliver their babies. In 1840, in Victoria’s reign, the Brownlow Street location was condemned, and the hospital was rebuilt on Edell Street. The new hospital had 40 beds. No regular medical reports were generated until 1870 (other than the 10 year summaries already mentioned). Over time, the hospital developed financial difficulties and gradually deteriorated (the building was in poor repair, the neighbourhood population was declining and the newer teaching hospitals had opened maternity wards). The British Lying-in Hospital for Married Women finally closed in 1913. The buildings were sold, and the funds raised were used with other monies to build special facilities for the British Hospital for Mothers and Babies in Woolwich.

*Statistics from Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine Journals cited below.

Sources include:

Google Books. The Laws Orders and Regulations of the British Lying-in Hospital for Married Women. By the Weekly Committee. (compiled in 1769) London: 1781. HEREGoogleBooks. Essays on the puerperal fever and other diseases peculiar to women. Edited by Fleetwood Churchill, M.D., M.R.I.A. London: Sydenham Society, 1849.HERE

GoogleBooks. THE DUBLIN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MEDICAL SCIENCE, VOL. 2. “The Memoirs of Dr. Mosse” (pages 565-596) Dublin: Hodges & Smith, 1816. HERE

Lost Hospitals of London. “British Lying-in Hospital”. (No date or author of post shown.) HERE

The National Archives. “The British Lying-in Hospital” (see Administrative/biographical background). HERE

Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine Journals. Volume 65, May 1972. (PDF) “The Lying-in Hospital 1747-“ by C. Keith Vartan, FR CGOG HERE

NCBI. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. “British maternal mortality in the 19th and carly 20th Centuries” by Geoffrey Champerlain. Nov. 2006. Vol. 99 (11): 559-563. HERE

Illustration from Wikimedia Commons: HERE

Interesting stuff, Lauren...

ReplyDeleteThank you, Regina! I appreciate the comment.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting. Seems like a costly ordeal, money which a single woman would not probably have. This also seems like a very good idea for a book.

ReplyDeleteI'm sure the three meals per day for at least 3 weeks were a huge boon to many of these women, as well as having someone to help them through the birth. A book set it such a facility could certainly have its share of drama and tragedy.

DeleteThat Dr Mosse sounds like a story waiting to be written....

ReplyDeleteHe seems quite a remarkable man, indeed.

DeleteVery interesting! The Lying-In hospitals were still in use until WWII - my father was born in one in London.

ReplyDelete