This is the beginning of ‘Early Modern Britain’. It was a time of Renaissance, English and Scottish Reformation and the debilitating English Civil War. And as always, to the victor goes the spoils. It was a time of rulers who were vain, greedy and downright corrupt. It was a time of adulterers, swindlers and cowards. And it was a time in British history when war would tear the country apart.

At the time of Elizabeth I’s death, England was changing dramatically. Let’s take a quick walk around London in this era. Imagine it’s been a rainy day and you’re out for a walk. Water puddles in dark alleys and the drains have overflowed down the middle of the cobbled streets as people huddle in their bedraggled hats and cloaks under dripping eaves. A horse-drawn carriage with clattering wheels speeds past on the uneven stones and carelessly splashes water on anyone who has braved the inclement weather. Normally the streets are packed with people and carriages and most days a blanket of smoke hangs over the city. The pollution gets in your eyes and the stonework of every building is blackened with it. Many of the houses are hundreds of years old and their timbers are deeply scarred with rat holes teaming with life. The houses are so close in the narrow alleys that occupants can reach out and touch hands with their neighbours if they chose to.

|

| London Bridge 1616 - public domain image |

But there is a reason you’re out and about on this day. After a downpour, you get the clearest view of the city with the sky washed clean of smog although the city air still smells of coal smoke. But it’s not just the burning coal that affects your nostrils. There are noxious fumes coming from the parts of the city where tanning is taking place and aromatic horse dung still lies in piles in the streets. As the day wears on, the smells are intensified by the stench from cesspits in cellars and from the carts filled with dung-pots left in the streets by rakers, whose business it is to empty private cesspits. Pigeons fly out from under the eaves of the old houses and their dropping leave white streaks on everything below. Rats scavenge behind crates avoiding the rubbish collectors in their horse-drawn carts collecting rotting matter from kitchens. You will be able to smell the flocks of sheep and herds of cattle driven by hoof to the abattoirs where their dung and blood add to the aroma on the streets.

Very soon, the streets will fill, not just with permanent residents who contribute to the overcrowding feeling, but hundreds of thousands of people who come to town daily to go to markets, fairs and to do business in the city. Very soon there will be crowds of people and animals everywhere so you know not to linger.

And then you listen to the sounds of London. Oxen are led into the city and slaughtered every day and the squeals and bellows they make in their pens is considerable and disturbing. There is the sound of iron wheels of coaches grinding over the cobbles and the hammering of blacksmiths and candlestick makers. There are the bells of rakers driving their dung-carts, the yelling of those gathering around a cockfight, the shouting of vendors pushing their carts, householders leaning out their windows and shouting to neighbours and you would hear the hourly chimes of more than a hundred churches. This London is so crowded, smelly and noisy you will barely be able to hear yourself think.

|

| Map of London 1593 - public domain image |

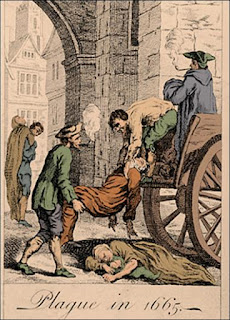

With the increase in population, diseases lurked around every corner and in every shadow. Everyday life meant being aware of the flu, dysentery, typhoid and smallpox and then there were always outbreaks of plague to be aware of. If you had a swelling in your armpits, if you were exceedingly thirsty, had a headache and if you were vomiting, you knew you were in serious trouble. You also knew to air your bedding in case there were fleas. You were certainly aware that fleas caused the disease but if you found any or you had been bitten, it was already too late because nobody had any idea how to treat it.

Plague broke out in London in 1603, 1636 and in 1665. Each time it killed a significant part of the population but each time London recovered. Of course, other towns as well as London were also periodically devastated by the plague. However, the plague of 1665, which affected London and other towns, was the last recorded outbreak and no one is very sure why because rats still scurried through the dark streets and people were still throwing dirty water and other rubbish from their windows into those same streets.

|

| Great Plague - public domain image |

17th century London was a dangerous place to live if you were poor but if you were rich, you were lucky. Transportation was no problem for you. You could easily walk from one street to another or you could travel by boat along the Thames. You could even hire a horse-drawn carriage called a ‘hackney carriage’ to take you around London if you desired. The streets were lit for the first time and an oil lamp was hung outside every tenth house. Not that the oil lamps gave you much light but they were certainly better than nothing at all, which was a fact of life on the other side of town.

The poor lived in houses east of the city where the streets were narrow and dark, well away from the wealthy people. Unfortunately, in these overcrowded, heavily populated areas, crime and danger was ever present and in a place where so many had so little, it’s not so surprising. Tempers and alcohol produced volatile situations and you made sure you kept a dagger close by to protect yourself. You learnt to keep your wits about you on the way home from the local pub especially as ale was the only available liquid to drink due to the unsanitary condition of the water. Looking at the rivers running with excrement, they had a good point.

|

| London Bridge over the Thames 1632 - public domain image |

However, improvements were on the way and a piped water supply was being created. Water from a reservoir travelled along elm pipes through the streets then along lead pipes to individual houses. Unfortunately, you had to pay to be connected to the supply and it was not cheap.

Because of the state of the water, keeping yourself clean wasn’t an easy task. You did that, not by washing, but by rubbing linen cloths over your body and through your hair to soak up the sweat. To take care of our body odour, you used perfume to improve the smell of your clothes. After taking care of your body odours, you had to take care of your breath. Thankfully, the Chinese had invented the toothbrush in 17th century and it had been introduced to England so there wasn’t as much need to chew cumin seeds or aniseed anymore. However, after brushing, you still rinsed out your mouth with white wine.

In the Middle Ages, ordinary people's homes were usually made of wood. Most of the poor lived in huts of two or three rooms while some families managed to survive in just one room. Your furniture, such as it was, remained very plain and basic because enhancements in furniture were not a part of your life.

But there were some more improvements on the horizon. In the 16th century, chimneys had been a luxury only the well-off could afford. Windows however took a little longer to become commonplace. Glass was definitely a luxury so those who could not afford it made do with linen soaked in linseed oil. However, during the 17th century glass became cheaper and by the late 17th century everyone had glass windows, sometimes casement windows (ones that opened on hinges). Later on, sash windows that slid up and down vertically to open and shut, were being introduced.

In the early 17th century people began eating with forks for the first time. New foods were being introduced into England such as bananas and pineapples and new drinks such as chocolate, tea and coffee had arrived. By late 17th century, coffee houses had popped up all around town and merchants and professional men alike could meet to read newspapers and talk shop.

|

| 17th Century coffee house - public domain image |

But not everyone was so lucky. Ordinary people existed on food like bread, cheese and onions and they ate pottage each and every day. This kind of strew was made by boiling grain in water to make a kind of porridge to which you added vegetables and pieces of meat or fish, if you could afford it.

Everyday life was a challenge and a hazard so it’s not surprising that the average life span in the 17th century was considerably shorter than today. Average life expectancy at birth was only 35 and many people died while they were still children. Out of all the people born, between one third and one half died before the age of about 16. However, if you could survive to your mid-teens you would probably live to your 50s or early 60s.

Stagecoaches were running regularly between the major English towns from the middle of the 17th century although the wealthy were still being carried around in sedan chairs while out and about in town. You paid dearly for the luxury of a stagecoach, and to top it off, they were very uncomfortable on the rough roads because none of them had springs. And of course, there was always the danger of highwaymen.

|

| Dick Turpin - public domain image |

The word ‘highwaymen’ conjures up characters like Dirk Turpin but these men were not so polite. If you were unlucky enough to come across these ruffians, there would also be another group cutting off your retreat. They would not only take your money and jewels, they took your clothes as well. Some killed their victims but most were left tied up in the forest in such a way that you could work yourself lose in an hour or two and make your way to the nearest inn or town in your underwear. If you survived the trip, you would be grateful to arrive unharmed but even these establishments housed thieves and unsavoury characters.

Heaven help you if you needed to see a doctor because barber-surgeons were still performing operations. Their knowledge of anatomy was improving but still left a lot to be desired. In 1628 William Harvey published his discovery of how blood circulates around the body and doctors had discovered how to treat malaria with bark from the cinchona tree.

|

| William Harvey - public domain image |

But even with these improvements, medicine was still handicapped by wrong ideas about the human body. Most doctors still thought that there were four fluids or 'humors' in the body - blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. Illness resulted when you had too much of one humor. When that happened, you needed to be bled. Nevertheless, during the 17th century, a more scientific approach to medicine emerged and some doctors thankfully began to question traditional ideas.

The 17th century would contain the most religious decade Britain had ever seen since the Middle Ages and society would be dominated by Christian beliefs and a willingness to severely punish people for ungodly behaviour. Puritanism was on the horizon

~~~~~~~~~~

Trisha Hughes is an Australian author living in Hong Kong. She is the author of her memoir ‘Daughters of Nazareth’ and she has completed the first two books in her V2V trilogy, ‘Vikings to Virgin - The Hazards of being King’ and ‘Virgin to Victoria - The Queen is dead. Long live the Queen’. This second in the series is due for release on 28th April this year.

You can contact Trisha via her websites: www.trishahughesauthor.com www.vikingstovirgin.com or via

Google+

Excellent post and description! Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing ... makes us realise how lucky we are to be living now, not then!

ReplyDeleteThank you for your fascinating post. It's no wonder the English poets loved Nature and the English country side!

ReplyDeleteI love the clarity of Trisha's writing style and her talented visual imagery.

ReplyDeleteI'm taking notes. Extraordinary prose. Sensory works.

ReplyDeletePassages from this are plagiarised directly from Ian Mortimer's excellent 'The Time Traveller's Guide to Restoration Britain'. The top of page 17, to be precise. What a shame he wasn't at least credited.

ReplyDelete