by Matthew Harffy

Throughout history, conflict has been described by the victors. This is especially true in the cases where the victorious army is part of a civilization that put great store in writing things down, such as the Romans. So it is that there are many accounts of battles from the Roman perspective, and far fewer details from the point of view of the so called barbarians. When we read these accounts by such luminaries as Tacitus and Suetonius, the modern observer must always factor in the politics of the time and what propagandist message the writer was hoping to put forward.

When we come to seventh century Britain, the wars and conquests are often only described in a couple of sources, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. Both of these works were penned by Christian Anglo-Saxon monks, who clearly had their own agenda in the telling of the rise to power of certain royal dynasties. If you are a monk sitting in a scriptorium in Wessex, you are most likely to give a certain Wessex-centric spin to your history. Where Bede was concerned, Northumbria was his home, what he knew best and the most powerful kingdom of Britain at the time. He was also a devout Christian, so of course, he wished to paint a picture of the history of the land that showed the power of God to work through kings who chose to accept Him. Bede clearly loved tales of kings who chose to be baptised and brought conversion and the teachings of Christ to their people. It is not that Bede, or indeed any of the scribes of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, openly twisted the truth or lied in their accounts, but I think all scholars would agree that those monks allowed their own beliefs and ideological leanings to bias their telling of history.

And so it is that we find there is often no information about the placement of troops in battles, or even where the battles took place. In many cases we have practically no idea of why the conflicts occurred, though it must be assumed that conquest and expansion of land must have been at the root of many disputes. These things were not deemed to be of importance to the monks writing the accounts. Frequently, all we are given are the names of the kings involved, and who was beaten. For example, the entry in the Chronicle for 633 says:

So not much to go on… we know the year, and who killed who and where. Not much else. If we then turn to Bede, we get some more details:

Bede goes on to tell how “great slaughter was made in the church or nation of the Northumbrians” by Cadwalla (also known as Cadwallon). He highlights that “one of the commanders, by whom it was made, was a pagan, and the other a barbarian, more cruel than a pagan; for Penda, with all the nation of the Mercians, was an idolater, and a stranger to the name of Christ; but Cadwalla, though he bore the name and professed himself a Christian, was so barbarous in his disposition and behaviour, that he neither spared the female sex, nor the innocent age of children, but with savage cruelty put them to tormenting deaths, ravaging all their country for a long time, and resolving to cut off all the race of the English within the borders of Britain.”

Bede goes on to tell how “great slaughter was made in the church or nation of the Northumbrians” by Cadwalla (also known as Cadwallon). He highlights that “one of the commanders, by whom it was made, was a pagan, and the other a barbarian, more cruel than a pagan; for Penda, with all the nation of the Mercians, was an idolater, and a stranger to the name of Christ; but Cadwalla, though he bore the name and professed himself a Christian, was so barbarous in his disposition and behaviour, that he neither spared the female sex, nor the innocent age of children, but with savage cruelty put them to tormenting deaths, ravaging all their country for a long time, and resolving to cut off all the race of the English within the borders of Britain.”

Here you can see Bede’s faith and his national pride at odds. Both Edwin and Cadwalla are Christian kings and yet Edwin is defeated and Cadwalla perpetrates horrific acts of cruelty in some kind of genocidal retribution. It is hard to know how much Bede has exaggerated the atrocities committed after Edwin’s death, but it is clear that the narrative is not an easy one for him. It is not the Northumbrian Christian king who is victorious, rather it is the pagan and the savage barbarian. And so the tales of battle often go in the seventh century. Bede revels in a good success story for a Christian monarch, but all too often those he deems to be most worthy of Christ’s blessing meet untimely, violent ends.

Such is the ultimate end of one of Bede’s favourite kings, Oswald of Northumbria, later Saint Oswald. But before his demise at the battle of Maserfield and his subsequent miracles and sainthood, Oswald provides Bede with the wonderful tale of his return from exile, his victory over the cruel defiler of the land, Cadwalla, and the expansion of Northumbria into the foremost kingdom of Britain.

Bede describes the decisive battle of Heavenfield between “Oswald, a man beloved by God” and the evil Cadwalla in greater detail than other engagements. But he does not focus on the battle itself, he concentrates on that which is important to him: the intervention of Christ in granting victory to the rightful king of Northumbria.

He tells at great length how Oswald erected a great cross and helped to hold it up while it was set in place. He then bid all of his warriors to pray, saying the following, “Let us all kneel, and jointly beseech the true and living God Almighty, in his mercy, to defend us from the haughty and fierce enemy; for He knows that we have undertaken a just war for the safety of our nation.”

The cross and the place then becomes the site of many miracles and the victory is really the start of the cult of Saint Oswald, which can probably be traced back to this moment and Bede’s subsequent immortalisation of it and the great Christian king of Northumbria.

Bede dedicates less space to the battle itself, describing how Oswald “advanced with an army, small, indeed, in number, but strengthened with the faith of Christ; and the impious commander of the Britons was slain, though he had most numerous forces, which he boasted nothing could withstand, at a place in the English tongue called Denises-burn, that is, Denis's-brook.”

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes Oswald’s ascension to power in a rather more matter of fact single line:

Would Penda, the staunchly pagan king of Mercia, have been the hero of Bede’s narrative if he had been Christian? He certainly was the supreme power in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms for decades during the first half of the seventh century, and was responsible for the deaths of five other kings.

Historians must try to peer into the primary sources and find the truth, peeling away bias and prejudice and propaganda. It is hard to piece together a true reflection of events from the sparse writings that have survived.

Conversely, the historical novelist revels in the scarcity of information, as it allows for creativity to fill in the gaps. The novelist relishes the not-so-subtle slant to one side or the other in the written accounts. This shines a light on how people thought at the time and can provide an author with a hook into a story, a flash of inspiration sparked from that very bias.

Battles are described by the victors. It is the historian's job to find the truth behind the victors' accounts. Some would argue that it is also the job of the novelist. I would disagree. It is the novelist's task to tell a good story, and that might just be a tale full of prejudice and untruths. You never know, it might even be from the perspective of the vanquished who never had the chance to write their own story.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Matthew Harffy is the author of the Bernicia Chronicles, a series of novels set in seventh century Britain.

The Serpent Sword, The Cross and the Curse and Blood and Blade are available on Amazon, Kobo, Google Play, and all good online bookstores.

Killer of Kings and Kin of Cain are available for pre-order on Amazon and all good online bookstores.

Website: www.matthewharffy.com

Twitter: @MatthewHarffy

Facebook: MatthewHarffyAuthor

Images:

La victoire de Tullus Hostilius sur les forces de Veies et de Fidena ---- Giuseppe Cesari [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

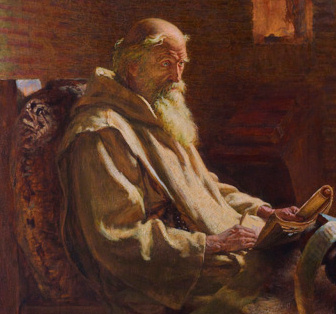

Portrait of Bede ---- By The original uploader was Timsj at English Wikipedia (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Holderness Cross ---- By portableantiquities [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Map of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms ---- Amitchell125 at en.wikipedia [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Heavenfield Cross ---- Oliver Dixon [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Throughout history, conflict has been described by the victors. This is especially true in the cases where the victorious army is part of a civilization that put great store in writing things down, such as the Romans. So it is that there are many accounts of battles from the Roman perspective, and far fewer details from the point of view of the so called barbarians. When we read these accounts by such luminaries as Tacitus and Suetonius, the modern observer must always factor in the politics of the time and what propagandist message the writer was hoping to put forward.

When we come to seventh century Britain, the wars and conquests are often only described in a couple of sources, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. Both of these works were penned by Christian Anglo-Saxon monks, who clearly had their own agenda in the telling of the rise to power of certain royal dynasties. If you are a monk sitting in a scriptorium in Wessex, you are most likely to give a certain Wessex-centric spin to your history. Where Bede was concerned, Northumbria was his home, what he knew best and the most powerful kingdom of Britain at the time. He was also a devout Christian, so of course, he wished to paint a picture of the history of the land that showed the power of God to work through kings who chose to accept Him. Bede clearly loved tales of kings who chose to be baptised and brought conversion and the teachings of Christ to their people. It is not that Bede, or indeed any of the scribes of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, openly twisted the truth or lied in their accounts, but I think all scholars would agree that those monks allowed their own beliefs and ideological leanings to bias their telling of history.

And so it is that we find there is often no information about the placement of troops in battles, or even where the battles took place. In many cases we have practically no idea of why the conflicts occurred, though it must be assumed that conquest and expansion of land must have been at the root of many disputes. These things were not deemed to be of importance to the monks writing the accounts. Frequently, all we are given are the names of the kings involved, and who was beaten. For example, the entry in the Chronicle for 633 says:

“A.D. 633. This year King Edwin was slain by Cadwalla and Penda, on Hatfield moor, on the fourteenth of October. He reigned seventeen years. His son Osfrid was also slain with him. After this Cadwalla and Penda went and ravaged all the land of the Northumbrians”

So not much to go on… we know the year, and who killed who and where. Not much else. If we then turn to Bede, we get some more details:

“Cadwalla; king of the Britons, rebelled against him [Edwin], being supported by Penda, a most warlike man of the royal race of the Mercians, and who from that time governed that nation twenty-two years with various success. A great battle being fought in the plain that is called Heathfield, Edwin was killed on the 12th of October, in the year of our Lord 633, being then forty-seven years of age, and all his army was either slain or dispersed.”

Bede goes on to tell how “great slaughter was made in the church or nation of the Northumbrians” by Cadwalla (also known as Cadwallon). He highlights that “one of the commanders, by whom it was made, was a pagan, and the other a barbarian, more cruel than a pagan; for Penda, with all the nation of the Mercians, was an idolater, and a stranger to the name of Christ; but Cadwalla, though he bore the name and professed himself a Christian, was so barbarous in his disposition and behaviour, that he neither spared the female sex, nor the innocent age of children, but with savage cruelty put them to tormenting deaths, ravaging all their country for a long time, and resolving to cut off all the race of the English within the borders of Britain.”

Bede goes on to tell how “great slaughter was made in the church or nation of the Northumbrians” by Cadwalla (also known as Cadwallon). He highlights that “one of the commanders, by whom it was made, was a pagan, and the other a barbarian, more cruel than a pagan; for Penda, with all the nation of the Mercians, was an idolater, and a stranger to the name of Christ; but Cadwalla, though he bore the name and professed himself a Christian, was so barbarous in his disposition and behaviour, that he neither spared the female sex, nor the innocent age of children, but with savage cruelty put them to tormenting deaths, ravaging all their country for a long time, and resolving to cut off all the race of the English within the borders of Britain.”Here you can see Bede’s faith and his national pride at odds. Both Edwin and Cadwalla are Christian kings and yet Edwin is defeated and Cadwalla perpetrates horrific acts of cruelty in some kind of genocidal retribution. It is hard to know how much Bede has exaggerated the atrocities committed after Edwin’s death, but it is clear that the narrative is not an easy one for him. It is not the Northumbrian Christian king who is victorious, rather it is the pagan and the savage barbarian. And so the tales of battle often go in the seventh century. Bede revels in a good success story for a Christian monarch, but all too often those he deems to be most worthy of Christ’s blessing meet untimely, violent ends.

Such is the ultimate end of one of Bede’s favourite kings, Oswald of Northumbria, later Saint Oswald. But before his demise at the battle of Maserfield and his subsequent miracles and sainthood, Oswald provides Bede with the wonderful tale of his return from exile, his victory over the cruel defiler of the land, Cadwalla, and the expansion of Northumbria into the foremost kingdom of Britain.

Bede describes the decisive battle of Heavenfield between “Oswald, a man beloved by God” and the evil Cadwalla in greater detail than other engagements. But he does not focus on the battle itself, he concentrates on that which is important to him: the intervention of Christ in granting victory to the rightful king of Northumbria.

He tells at great length how Oswald erected a great cross and helped to hold it up while it was set in place. He then bid all of his warriors to pray, saying the following, “Let us all kneel, and jointly beseech the true and living God Almighty, in his mercy, to defend us from the haughty and fierce enemy; for He knows that we have undertaken a just war for the safety of our nation.”

The cross and the place then becomes the site of many miracles and the victory is really the start of the cult of Saint Oswald, which can probably be traced back to this moment and Bede’s subsequent immortalisation of it and the great Christian king of Northumbria.

Bede dedicates less space to the battle itself, describing how Oswald “advanced with an army, small, indeed, in number, but strengthened with the faith of Christ; and the impious commander of the Britons was slain, though he had most numerous forces, which he boasted nothing could withstand, at a place in the English tongue called Denises-burn, that is, Denis's-brook.”

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes Oswald’s ascension to power in a rather more matter of fact single line:

“Oswald also this year succeeded to the government of the Northumbrians, and reigned nine winters.”

Would Penda, the staunchly pagan king of Mercia, have been the hero of Bede’s narrative if he had been Christian? He certainly was the supreme power in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms for decades during the first half of the seventh century, and was responsible for the deaths of five other kings.

Historians must try to peer into the primary sources and find the truth, peeling away bias and prejudice and propaganda. It is hard to piece together a true reflection of events from the sparse writings that have survived.

Conversely, the historical novelist revels in the scarcity of information, as it allows for creativity to fill in the gaps. The novelist relishes the not-so-subtle slant to one side or the other in the written accounts. This shines a light on how people thought at the time and can provide an author with a hook into a story, a flash of inspiration sparked from that very bias.

Battles are described by the victors. It is the historian's job to find the truth behind the victors' accounts. Some would argue that it is also the job of the novelist. I would disagree. It is the novelist's task to tell a good story, and that might just be a tale full of prejudice and untruths. You never know, it might even be from the perspective of the vanquished who never had the chance to write their own story.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Matthew Harffy is the author of the Bernicia Chronicles, a series of novels set in seventh century Britain.

The Serpent Sword, The Cross and the Curse and Blood and Blade are available on Amazon, Kobo, Google Play, and all good online bookstores.

Killer of Kings and Kin of Cain are available for pre-order on Amazon and all good online bookstores.

Website: www.matthewharffy.com

Twitter: @MatthewHarffy

Facebook: MatthewHarffyAuthor

Images:

La victoire de Tullus Hostilius sur les forces de Veies et de Fidena ---- Giuseppe Cesari [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Bede ---- By The original uploader was Timsj at English Wikipedia (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Holderness Cross ---- By portableantiquities [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Map of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms ---- Amitchell125 at en.wikipedia [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Heavenfield Cross ---- Oliver Dixon [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

I requested Blood and Blade on Netgalley. I saw Edoardo Albert recommending it, and he usually has good taste- and frankly, I just love all things seventh century.

ReplyDeleteThat's great! I hope you enjoyed it and I look forward to reading your review. :-)

DeleteHave not started it yet, but I hope to soon.

DeleteHave not started it yet, but hope to soon! Might have to borrow 'The Serpent Sword' from the library first.

DeleteBede was a pretty unreliable source for why anything happened because - as you say - he had his own agenda. Ironically, the biggest tragedy about the scarcity of written sources in the early English period is not what they leave out but the emphasis historians have put on what they actually do say.

ReplyDeleteThere can never be a 'truth' about events that happened in seventh century England. It is, however, vital to understand the sources that people 'build' their interpretation of the past on. As such, bias is an important factor, but more so is an understanding of the time and space that have elapsed between the 'written' account of the event, and the event itself, and perhaps more importantly, the reason that the source has survived to the modern day. For instance, whether you believe in the existence of a now lost Mercian Chronicle or not, it's important to consider why it might not have survived i.e. Vikings burnt all of Mercia and if there had been a Mercian Chronicle - what would they have said about Edwin, Oswald and Oswiu? Why did Bede's words survive? Where did it survive? Do all editions mention the same details? Was it used to write the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle? How many editions have survived?

ReplyDeleteAlso, it's very important that the historian and the fiction writer 'step away' from the causality of events - look at them from the viewpoints of the people involved. They didn't know when men were going to die? When battles would ultimately be met?

To be an excellent historian it's imperative that every single fact is questioned - even the fact that Bede gives Penda three great battles must be queried because there was power in the number three - look at the Welsh Triads. To be a good writer, it's necessary to play with the haziness of events, but without first being a historian, any fiction will fall short and readers will be pulled even deeper into the 'haze' of history, where 'truth' no longer exists - for they will 'understand' the story as presented by the fiction writer, not the historian! Fiction writers are, after all, merely continuing Bede's very long legacy, and even their motives must be questioned for bias.

Interesting and thought-provoking points, MJ. I think perhaps we disagree on the role of the fiction writer. I don't think a novelist has a duty to be truthful to reality, only truthful to their story and themselves. The reader must surely know that they are reading fiction and therefore, if they choose to decide to believe what a novel contains is historical "truth", that is their concern and not that of the author.

DeleteGood post, Matthew. I find it interesting that there exists an underlying assumption that modern historians (used in its broadest sense of people who record and interpret history) are less biased and hence more reliable than ancient writers. What do folk think?

ReplyDeleteAs for Bede, he is a good collator of information. But his intent is clear: political motives of kings are secondary; the story of the sprouting and blossoming of Christianity among the 'gens anglorum' (an interestingly biased construction, we might say) is his chief concern, and I would argue that Bede's readers were meant to feel the same. So the glorious Oswald becomes the Anglo-Saxon version of the Old Testament Joshua or Abraham, the Lord's army fighting against a bigger army and defeating it in the name of Yahweh!

If it's not creating Old Testament style narratives, then it's writing an account to rival anything in the Acts of the Apostles. For example, Bede's account of the arrival of the Gregorian mission to Kent and the conversion of King Ethellbert would sit rather well in the New Testament, I think.

Good post, Matthew. I find it interesting that there exists an underlying assumption that modern historians (used in its broadest sense of people who record and interpret history) are less biased and hence more reliable than ancient writers. What do folk think?

ReplyDeleteAs for Bede, he is a good collator of information. But his intent is clear: political motives of kings are secondary; the story of the sprouting and blossoming of Christianity among the 'gens anglorum' (an interestingly biased construction, we might say) is his chief concern, and I would argue that Bede's readers were meant to feel the same. So the glorious Oswald becomes the Anglo-Saxon version of the Old Testament Joshua or Abraham, the Lord's army fighting against a bigger army and defeating it in the name of Yahweh!

If it's not creating Old Testament style narratives, then it's writing an account to rival anything in the Acts of the Apostles. For example, Bede's account of the arrival of the Gregorian mission to Kent and the conversion of King Ethellbert would sit rather well in the New Testament, I think.