The English Civil War in the 1640’s fired many passions on both sides of the conflict, often making for strange bedfellows with shifting loyalties. Women were the displaced heroes, left to defend estates, protect their family’s possessions and honour, raise money for the cause, and mend the shattered fences of broken alliances. Letter writing filled the void left by absent loved ones, elevating communication in some instances to an art form.

|

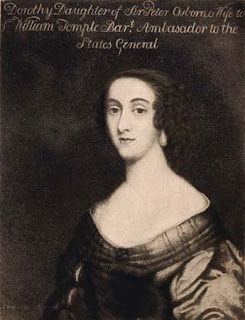

| Dorothy, Lady Temple by Gaspar Netscher National Portrait Gallery NPG3813 |

|

| Chicksands Priory: Ashley3D via Visual hunt / CC BY-SA |

A stalwart example to his youngest child, Dorothy, Sir Peter demonstrated the value of loyalty, even in the face of seemingly lost causes. Left behind at Chicksands, their country estate in Bedfordshire, Dorothy experienced the kind of loss to family and fortune that heavily impacts one’s formative years. She was just fifteen in 1642 when the war broke out, and by the time the conflict was over, her status and prospects had changed forever.

But against this tumultuous and ruinous background, Dorothy fell in love. Her choice was a good one, for he was a charming, intelligent, handsome and amiable young man who quickly fell for her as well.

Dorothy Osborne met William Temple at the age of twenty-one in 1648 on progress to France with her youngest brother, Robin. The Royalist cause was a lost one and the Osborne estates forfeit to Parliament. Moving his family to France seemed like the only option for Sir Peter.

“I was so altered, from a cheerful humour that was always alike, never over merry, but always pleased, I was grown heavy, and sullen, forward and discomposed.” Dorothy Osborne

But against this tumultuous and ruinous background, Dorothy fell in love. Her choice was a good one, for he was a charming, intelligent, handsome and amiable young man who quickly fell for her as well.

“…as those romances are best which are likest true stories, so are those true stories which are likest romances.” William Temple to Dorothy Osborne

Dorothy Osborne met William Temple at the age of twenty-one in 1648 on progress to France with her youngest brother, Robin. The Royalist cause was a lost one and the Osborne estates forfeit to Parliament. Moving his family to France seemed like the only option for Sir Peter.

|

| Sir William Temple National Portrait Gallery NPG3812 |

William’s family had fought on the Parliamentary side, which had similarly depleted their resources. At twenty years old, he was on progress to Europe for his education, and found himself in the company of Dorothy and her brother Robin. Dorothy was immediately impressed with this captivating fellow traveller.

According to biographer Jane Dunn in her book, “His easy manners, interest in others and natural charm were so infectious that his sister Martha claimed that on a good day no one, male or female, could resist him.”

While William awaited departure by boat to France with Dorothy on the Isle of Wight, Dorothy’s brother Robin got into a bit of trouble. Infuriated by the imprisonment of King Charles I in Carisbrooke Castle, Robin ran back to their inn and etched an incendiary quotation in Latin into the windowpane, implying a reversal in current political circumstances. According to Dunn, the last line of the well-known quotation was, “Then was the King’s wrath pacified.”

Robin was arrested by Parliamentary officials and taken to trial in the name of Governor Robert Hammond. Dorothy came forward to claim the deed was hers, not Robin’s, hoping the officials would be more lenient with a woman. William, moved by Dorothy’s loyalty and love for her brother, spoke on her behalf, and since Governor Hammond was his cousin and son of the man who had educated William in his home as a boy, the officials relented and let the brother and sister go.

William, now falling in love with Dorothy, delayed his European tour to stay on with the Osborne family in St. Malo, France, where Sir Peter Osborne and his wife were exiled. After a month, however, William’s father, Sir John Temple, heard of his son’s delay and sternly ordered him by letter to depart on his tour. William obeyed, but his passion for Dorothy and hers for him was such that promises were made, and thereafter, Dorothy Osborne and William Temple were devoted to each other.

For the next seven years, Dorothy and William would fight familial duty, ardent suitors, an unfriendly regime, and family supporters to keep their pact to marry only each other. Their constancy in uncertain times and against such pressure is remarkable, and theirs is one of the truly great romances of the seventeenth century. The letters they shared over these years, coupled with infrequent and surreptitious meetings, served to maintain a dedicated bond that only grew stronger the more opposition they encountered.

According to biographer Jane Dunn in her book, “His easy manners, interest in others and natural charm were so infectious that his sister Martha claimed that on a good day no one, male or female, could resist him.”

While William awaited departure by boat to France with Dorothy on the Isle of Wight, Dorothy’s brother Robin got into a bit of trouble. Infuriated by the imprisonment of King Charles I in Carisbrooke Castle, Robin ran back to their inn and etched an incendiary quotation in Latin into the windowpane, implying a reversal in current political circumstances. According to Dunn, the last line of the well-known quotation was, “Then was the King’s wrath pacified.”

Robin was arrested by Parliamentary officials and taken to trial in the name of Governor Robert Hammond. Dorothy came forward to claim the deed was hers, not Robin’s, hoping the officials would be more lenient with a woman. William, moved by Dorothy’s loyalty and love for her brother, spoke on her behalf, and since Governor Hammond was his cousin and son of the man who had educated William in his home as a boy, the officials relented and let the brother and sister go.

William, now falling in love with Dorothy, delayed his European tour to stay on with the Osborne family in St. Malo, France, where Sir Peter Osborne and his wife were exiled. After a month, however, William’s father, Sir John Temple, heard of his son’s delay and sternly ordered him by letter to depart on his tour. William obeyed, but his passion for Dorothy and hers for him was such that promises were made, and thereafter, Dorothy Osborne and William Temple were devoted to each other.

For the next seven years, Dorothy and William would fight familial duty, ardent suitors, an unfriendly regime, and family supporters to keep their pact to marry only each other. Their constancy in uncertain times and against such pressure is remarkable, and theirs is one of the truly great romances of the seventeenth century. The letters they shared over these years, coupled with infrequent and surreptitious meetings, served to maintain a dedicated bond that only grew stronger the more opposition they encountered.

Once the extent of their attachment was discovered, William’s family forbade him to communicate with Dorothy, but he disobeyed them. Few of his letters to her have survived, as the couple promised to destroy all their letters to each other to avoid detection. He did write French-style romances for her, which he knew she admired, and told her to read them as letters from him.

Dorothy, in the face of abuse and histrionics from her possessive brother, Henry, who lived with her after the Osborne estates were restored at Chicksands, duly destroyed her precious letters, but her desperation to receive them was clear.

William, blessed with more physical freedom from his disapproving father, could not bear to destroy her words, and so Dorothy’s letters to him were lovingly preserved.

At times, his devotion and terror at losing her shows in her response to his letters:

The couple, secretly pledged to each other but forbidden to wed, fended off a number of suitors brought forth by their families. Sir John Temple, determined that his only son and heir should marry well, grew increasingly impatient with his son’s stubborn attachment to an unsuitable woman from a disgraced family with no dowry.

Dorothy, a known beauty, fended off many suitors, some encouraged by her irate brother Henry, and some who sought Dorothy out on their own. These included such illustrious personages as her cousin, Thomas Osborne, Lord Danby and later 1st Duke of Leeds; Henry Cromwell, second son of Lord Protector of the Commonwealth Oliver Cromwell; and Justinian Isham, English scholar and royalist advisor.

William’s fear that Dorothy would take a better offer and break their covenant stayed with him throughout their courtship, as he struggled to find the income and position that would allow him marry and support a family with the woman he loved.

William’s melancholy reached a fever in 1654, as Dorothy, nearing 28 years of age, began to hint that she might release him from their pact. Considering the waning fortunes of her family, her dwindling prospects on the marriage market with her many refusals, and William’s frustration that endangered his health, Dorothy may have been trying to do the right thing for them both.

William panicked and fell so despondent that Dorothy begged him to protect himself from his own nature, the “Violence of your passion.” She wrote:

Sally A. Moore is a freelance writer and an award-winning poet and novelist from Kingston, Ontario in Canada. Represented by The Rights Factory Literary Agency in Toronto, her writing credits include articles and creative fiction, as well as poetry prizes from the Ontario Poetry Society and the Montreal International Poetry Prize competition. Sally is Past President of the Writers’ Community of Durham Region (WCDR), a member of the Historical Novel Society, and the recipient of the Len Cullen Writing Scholarship. Sally holds certificates of achievement from Humber School for Writers and a diploma with Distinction in Commercial Communications. Excerpts of her historical fiction/fantasy trilogy, Legend of Three Crowns, a work in progress, can be seen on her web site. www.samoorewrites.com

Connect with Sally:

twitter: @SallyMoore11

LinkedIn: SallyMoore777

Writing Services Web Site: SaMooreWrites

Web Portal, Historical Fiction: LegendofThreeCrowns

“Madam, I count all that time but lost which I lived without knowing you . . . it is impossible to tell you how much I have died since I left you, for I have done it as often as I have thought of you, and thought of you as often as I have breathed.” Sir William Temple

Dorothy, in the face of abuse and histrionics from her possessive brother, Henry, who lived with her after the Osborne estates were restored at Chicksands, duly destroyed her precious letters, but her desperation to receive them was clear.

“O if you do not send me long letters then you are the cruellest person that can be. If you love me you will and if you do not I shall never love my self.”

William, blessed with more physical freedom from his disapproving father, could not bear to destroy her words, and so Dorothy’s letters to him were lovingly preserved.

At times, his devotion and terror at losing her shows in her response to his letters:

“I know your humour is strangely altered from what it was, and I am sorry for it,” she wrote. “Melancholy must needs do you more hurt . . . therefore if you loved me you would take heed of it. Can you believe that you are dearer to me than the whole world besides and yet neglect yourself?”

The couple, secretly pledged to each other but forbidden to wed, fended off a number of suitors brought forth by their families. Sir John Temple, determined that his only son and heir should marry well, grew increasingly impatient with his son’s stubborn attachment to an unsuitable woman from a disgraced family with no dowry.

Dorothy, a known beauty, fended off many suitors, some encouraged by her irate brother Henry, and some who sought Dorothy out on their own. These included such illustrious personages as her cousin, Thomas Osborne, Lord Danby and later 1st Duke of Leeds; Henry Cromwell, second son of Lord Protector of the Commonwealth Oliver Cromwell; and Justinian Isham, English scholar and royalist advisor.

|

| Justinian Isham by Peter Lely [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons |

Dorothy seems to have been on good terms with some of them, in spite of her arguments with her brother and ailing father over her constant refusals. Henry Cromwell remained a lifelong friend, and made a present of two Irish greyhounds she wanted. William, not to be undone, sent her another, charging her with loving this single devoted animal the most.

Dorothy was quick to reassure him:

Dorothy was quick to reassure him:

“I have defended him from the envy and the malice of a troupe of greyhounds that used to be in favour with me, and he is so sensible of my care over him that he is pleased with nobody else and follows me as if we had been of long acquaintance.”

William’s fear that Dorothy would take a better offer and break their covenant stayed with him throughout their courtship, as he struggled to find the income and position that would allow him marry and support a family with the woman he loved.

William’s melancholy reached a fever in 1654, as Dorothy, nearing 28 years of age, began to hint that she might release him from their pact. Considering the waning fortunes of her family, her dwindling prospects on the marriage market with her many refusals, and William’s frustration that endangered his health, Dorothy may have been trying to do the right thing for them both.

William panicked and fell so despondent that Dorothy begged him to protect himself from his own nature, the “Violence of your passion.” She wrote:

“Let me beg then that you will leave off those dismal thoughts. I tremble at the desperate things you say in your letter.”

William’s father, seeing the suffering of his son, and the devotion of William’s heart, finally relented. He and Dorothy’s brother (her ailing father had passed away) wrangled over the terms, but the couple joyously made plans to marry in October of 1654, heedless of the settlement.

Dorothy came to London with her aunt, Elizabeth Danvers, as chaperone, and the lovers were reunited. One can only imagine the soaring joy as they stood together, finally embraced in each other’s arms. Sadly, tragedy struck this long-suffering couple. Dorothy fell seriously ill with smallpox.

William stayed by her side, refusing to leave, and helped nurse his love. Her condition was dire, and she was expected to perish, but William would not give up. So strong was Dorothy’s determination to live and be joined with her love, that she stayed the course and through a terrible ordeal she fought for her life.

William rejoiced when her condition suddenly improved. “He was happy when he saw [her life] secure, his kindness having greater ties than that of her beauty,” his sister Martha, Lady Giffard, later recalled. “William had long recognised that Dorothy’s beauty sprang from a deeper source than an unblemished creamy skin.” (Jane Dunn, Read My Heart).

William and Dorothy were married on Christmas Day, 1654, and while their life together was fraught with challenges—her brother’s continued objections, financial difficulties due to the delayed settlement of her dowry and William’s inheritance, multiple miscarriages and infant deaths, and numerous separations with the changing political landscape—their love remained constant and unwavering.

After seven long years, the anguish and determination of two people desperately in love was rewarded, and is a testament to the true love and loyalty of William Temple and Dorothy Osborne. Most of us should be so lucky.

“Nothing can alter the resolution I have taken of setting my whole stock of happiness upon the affection of a person that is dear to me whose kindness I shall infinitely prefer before any other consideration whatsoever.” Dorothy Osborne to William Temple

Dorothy came to London with her aunt, Elizabeth Danvers, as chaperone, and the lovers were reunited. One can only imagine the soaring joy as they stood together, finally embraced in each other’s arms. Sadly, tragedy struck this long-suffering couple. Dorothy fell seriously ill with smallpox.

William stayed by her side, refusing to leave, and helped nurse his love. Her condition was dire, and she was expected to perish, but William would not give up. So strong was Dorothy’s determination to live and be joined with her love, that she stayed the course and through a terrible ordeal she fought for her life.

William rejoiced when her condition suddenly improved. “He was happy when he saw [her life] secure, his kindness having greater ties than that of her beauty,” his sister Martha, Lady Giffard, later recalled. “William had long recognised that Dorothy’s beauty sprang from a deeper source than an unblemished creamy skin.” (Jane Dunn, Read My Heart).

William and Dorothy were married on Christmas Day, 1654, and while their life together was fraught with challenges—her brother’s continued objections, financial difficulties due to the delayed settlement of her dowry and William’s inheritance, multiple miscarriages and infant deaths, and numerous separations with the changing political landscape—their love remained constant and unwavering.

After seven long years, the anguish and determination of two people desperately in love was rewarded, and is a testament to the true love and loyalty of William Temple and Dorothy Osborne. Most of us should be so lucky.

~~~~~~~~~~~

Sources:

The Love Letters of Dorothy Osborne to Sir William Temple (1888) edited by Edward Abbott Parry

Dorothy Osborne’s 77 surviving letters (now held in the British Library ADD. MSS. 33975)

Read My Heart A Love Story in England’s Age of Revolution, by Jane Dunn, 2008, Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

The Constant Desperado by Sir William Temple

Sources:

The Love Letters of Dorothy Osborne to Sir William Temple (1888) edited by Edward Abbott Parry

Dorothy Osborne’s 77 surviving letters (now held in the British Library ADD. MSS. 33975)

Read My Heart A Love Story in England’s Age of Revolution, by Jane Dunn, 2008, Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

The Constant Desperado by Sir William Temple

Sally A. Moore is a freelance writer and an award-winning poet and novelist from Kingston, Ontario in Canada. Represented by The Rights Factory Literary Agency in Toronto, her writing credits include articles and creative fiction, as well as poetry prizes from the Ontario Poetry Society and the Montreal International Poetry Prize competition. Sally is Past President of the Writers’ Community of Durham Region (WCDR), a member of the Historical Novel Society, and the recipient of the Len Cullen Writing Scholarship. Sally holds certificates of achievement from Humber School for Writers and a diploma with Distinction in Commercial Communications. Excerpts of her historical fiction/fantasy trilogy, Legend of Three Crowns, a work in progress, can be seen on her web site. www.samoorewrites.com

Connect with Sally:

twitter: @SallyMoore11

LinkedIn: SallyMoore777

Writing Services Web Site: SaMooreWrites

Web Portal, Historical Fiction: LegendofThreeCrowns

I read Read My Heart some years ago, and really enjoyed it. Than you for this interesting post!

ReplyDeleteThank-you Lauren! Jane Dunn presented a thorough picture of their life together, and Dorothy's letters are so interesting to read: so witty, devoted and intimate. You can feel the passion and secrecy of their devotion.

DeleteThe English Civil War was a time of such upheaval, and it ruined the fortunes of both families, which kept the couple from obtaining the necessary approval of their parents to wed. But one wonders: if not for the Civil War, would they even have met? Just another contradiction of a senseless war.

Such a poignant story. Well done!

ReplyDeleteThank-you for the opportunity, Cryssa. I love the history presented here on the EHFA site, and your own blog as well. Remember the days when we had to trudge to the library in two feet of snow to scour the biography stacks and get our history fix? We are in a glorious age.

DeleteBeautiful story, so well written, and I loved the letters. These women of the Civil War lived through extraordinary times. We have the advantage of looking back at their lives - I can only imagine the fear and uncertainty they confronted every day. Thanks for a great read!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for your kind words, Elizabeth. I am truly inspired by the story of these two extraordinary people and grateful to be able to share it here. The women of the ECW are often overlooked for their contribution to the war and to English history, but they showed courage, love and determination. In a time of rifts and divided loyalties, these women can be credited as the ones who tried to hold England and its people together. Now, that's worthy of praise and admiration in any age.

Delete