by Sally O’Reilly

Writing historical fiction started as a pleasure and has turned into an addiction. I grew up reading Rosemary Sutcliff, Henry Treece and Baroness Orczy. I also admire the audacious writing of Angela Carter, Sarah Waters and Jeanette Winterson, who in various ways have mined the past and the conventions of storytelling to create their own individual worlds of darkness, fakery and magic. (Sarah Waters, who ‘gulls’ the reader in the brilliant ‘Affinity’ was a particular inspiration.)

I think that what attracts me most about historical fiction is the idea that it can take you through a portal into another world – the past – and in that sense it’s like the fantasy books that I also loved as a child, particularly the Narnia series. C.S. Lewis has an exceptional talent for bringing a scene alive, and for making fantastical places seem solid and believable.

I have always loved Shakespeare, and since studying it at school my favourite play has been ‘Macbeth’. Its dark, mysterious atmosphere lingers in the memory, and the three witches wield a preternatural power that is never challenged. But I needed to find a way to tell a story about this play that had a strong female character at its heart. Lady Macbeth herself was my first choice, but I couldn’t make this work.

Then, during my research, I stumbled on a character who has been almost entirely forgotten: Aemilia Bassano Lanyer, the first woman to be published professionally as a poet in England.

Lanyer’s poetry collection ‘Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum’ includes a justification of Eve and a retelling of the Crucifixion from the point of view of the women in the New Testament. Published in 1611, it is dedicated to a roll call of aristocratic women, starting with Queen Anne, the wife of James I. This is the way in which a professional male poet would introduce his work, and Lanyer’s volume is the only surviving example of a woman writing in this way at such an early date.

Lanyer’s poetry collection ‘Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum’ includes a justification of Eve and a retelling of the Crucifixion from the point of view of the women in the New Testament. Published in 1611, it is dedicated to a roll call of aristocratic women, starting with Queen Anne, the wife of James I. This is the way in which a professional male poet would introduce his work, and Lanyer’s volume is the only surviving example of a woman writing in this way at such an early date.

The facts of Aemilia Lanyer’s life are dramatic: she was the illegimate child of Jewish immigrant musicians who played at the Tudor court; her father died when she was seven and she was apparently educated at court or in a great house. At seventeen she became the mistress of the Lord Chamberlain, Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon; six years later she was pregnant and married off to a cousin, Alfonso Lanyer, a recorder player who spent her dowry in a year. She later became a client of the astrologer and physician Simon Forman, who talked to her about summoning demons. (Most of these facts have been gleaned from his journal.) And she is one of the women who may have been Shakespeare’s ‘Dark Lady’ the inspiration for the later sonnets.

But who is Shakespeare’s Dark Lady? Was she a real person, or a poetic convention? Opinion has been divided over the years, but the current view is that the sonnets are addressed to real people. However, we don’t know the identity of the Fair Youth (the subject of the earlier sonnets in the sequence) or the Dark Lady, and it’s unlikely that we ever will. In my novel, the Fair Youth is Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, to whom Shakespeare dedicated his poems ‘Venus & Adonis’ and ‘The Rape of Lucrece’. Wriothesley was handsome, impulsive and immensely wealthy which fitted in with my themes.

Shakespeare never used the term ‘Dark Lady’ and both this title and her identity are part of the carefully assembled edifice of pseudo facts that are part of the Shakespeare legend. All we actually have to go on are the plays and poems that survive. The sonnets dedicated to this mysterious woman are anguished and passionate, and suggest that the poet is in the grip of a painful sexual obsession. The myth of the Dark Lady is inspired by the fact that he describes his lover as having black hair and ‘dun’ skin. This was an unfashionable look in Early Modern times: the ideal was fair hair and a pale complexion.

Aemilia Lanyer is one of several candidates for the Dark Lady title, and researchers are continually discovering new possibilities. For example, in 2013 Dr Aubrey Burl, a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, suggested that the Dark Lady was Aline Florio, the wife of an Italian translator. [Link below] Burl put forward eight possible candidates, but chose Aline Florio because she had dark hair and was married, musical, a mother and unfaithful to her husband. (Aemilia Lanyer fits the bill equally well, I have to say.)

Other candidates who were married to men in Shakespeare’s world include Marie Mountjoy, the wife of Christopher Mountjoy, a costume maker and Shakespeare’s landlord in Silver Street, Jane Davenant, wife to Oxford tavern keeper John Davenant, whose son William, was a prominent figure in the seventeenth century theatre and claimed to be Shakespeare’s son and Jacqueline Field, the wife of Stratford-born Richard Field who printed Shakespeare’s poetry in London. Very little is known about the lives or the characters of these women, and they are possible mistresses primarily because of their proximity to Shakespeare. (For example, it has been suggested that the fact that Field printed Shakespeare’s poetry with such accuracy and attention to detail suggests that Shakespeare had a direct hand in their production, and would therefore have been a frequent visitor to the Field’s print shop.)

Lucy Morgan is an interesting candidate, and has inspired both Anthony Burgess and (more recently) Victoria Lamb. Again, there are few surviving facts about her life, but she is thought to have been one of Queen Elizabeth I’s lesser known ladies in waiting, and may also have been the notorious ‘Lucy Negra’, a prostitute in London. If so, her fall was as dramatic as that of Aemilia Lanyer, and the name ‘Negra’ suggests that she was of African descent.

In his 1977 novel ‘Nothing Like the Sun’ Burgess suggests that the relationship between Shakespeare and Lucy is mutually destructive and has tragic consequences for them both. The story is steeped in squalor and disease, and though I went some distance in this direction myself, I couldn’t bear to create a relationship devoid of hope or happiness. However, his novel is truly dazzling in terms of its language and imaginative power.

Mary Fitton and Penelope Devereux were from aristocratic families, and more is known about their lives. Mary Fitton (1578 – 1647) was another of the Queen’s ladies. She had affairs with William Herbert, the Earl of Pembroke (among others) and had children by various men. Herbert was younger than she was, and may be the mysterious ‘Mr WH’ to whom the sonnets are dedicated. Fitton’s relationship with Pembroke was certainly scandalous, and he was sent to the Fleet Prison after Fitton became pregnant with his child. He admitted he was the father, but refused to marry her. More affairs and two marriages followed. Both Frank Harris and George Bernard Shaw make Fitton the Dark Lady in their books, but while Harris suggests that Shakespeare was broken by the relationship, Shaw’s view is that heartbreak was one of his many inspirations.

The most privileged of all possible Dark Ladies is Penelope Devereux (1563- 1607), who became Countess of Devonshire. She was the sister of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, the Queen’s reckless and spoiled favourite, and is also thought to be the inspiration for Stella in Philip Sidney's ‘Astrophel and Stella’ sonnets. Another scandal-prone woman, she married Robert Rich, but had a notorious affair with Charles Blount, Baron Mountjoy, and eventually divorced Rich and married Blount in an unlicensed ceremony. This was a shocking break with canon law, and James I banished them from court. (They were both dead within two years, a sad little footnote to these dramatic events.)

Beautiful and talented, Devereux would have been a glittering figure in the Early Modern cultural scene. She had blonde hair, a point against her perhaps, but dark eyes, and was certainly an inspiration for other poets. If Shakespeare had an affair with her, it would have been a heady and dangerous experience, given her high status in terms of both social class and sexual allure.

So why did I choose Aemilia Lanyer, in the face of such stiff competition? To be honest, I didn’t even know there were so many other candidates until I was well into my first draft. When I discovered that she had existed, a light went on in my head, and I knew that I wanted to write a story about this astonishing person. I was particularly attracted by her status as a poet, and her fall from grace in every other aspect of her life.

One of the themes of my story is ambition and over-reaching – ‘Macbeth’ dramatizes these ideas with great intensity. Aemilia’s own experience is an illustration of this. Early Modern London was a bit like 21st century Hollywood, a place to go and make your fortune and compete for attention. Those who succeeded could gain huge wealth, but there was no safety net for those who failed.

At one point, she was centre stage, a confidante of the Lord Chamberlain, living in close proximity to the Queen herself. What must she have felt, when she was ejected from her suite of rooms in Whitehall Palace? And her home was now a small house in Long Ditch, a narrow street overlooked by some of the great houses of London? I could sense the claustrophobia and panic. And yet, rather than disappearing into the drudgery of domesticity, she wrote her poetry and found a publisher and addressed her work to the greatest women in the land. Five hundred years later, we can still read her words, and hear her voice.

This is fact. From fact comes supposition – suppose she was the Dark Lady? How would she, an aspiring poet, feel about being the subject of these poems? The emotion is undeniable, but they are wracked with pain and spiced with venom. From supposition comes imagination – I decided to try and recreate Aemilia Lanyer in a fusion between fact and fiction, and to tell her the story of her flawed love affair with Shakespeare from her partial and intense point of view.

By doing this, I was able to explore the way in which experience feeds into artistic creation, and rivalry can motivate it. I also wanted to show the obsessive, ruthless aspect of creativity, in which even the worst experiences feed artistic invention. (As Graham Greene said, there is a splinter of ice in the heart of every writer.) The relationship between Shakespeare and Lanyer is more than just an anguished love affair, it is a battle of wills and a clash of egos. In that sense, I felt that her story could be an inspiration for every writer who has struggled to be heard, and for every woman who resists the constraints of convention and domesticity.

Salve Deus - author: Author usage licensed: Creative Commons

Burl's Article

[This article is an Ediotrs' Choice post, which originally appeared on 28th March, 2014]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

‘Dark Aemilia’ is published by Myriad Editions on March 27th and by Picador US in June.

Sally O’Reilly is the author of How to be a Writer and two contemporary novels The Best Possible Taste and You Spin Me Round both published by Penguin. Her short stories have appeared in the UK, Australia and South Africa. She worked as a journalist and editor for Christian Aid and Barnardo’s, and has freelanced for the Guardian, Sunday Times, Evening Standard and New Scientist. Sally has a PhD in Creative Writing from Brunel University and teaches Creative Writing at the Open University. Dark Aemilia is her first historical novel.

Writing historical fiction started as a pleasure and has turned into an addiction. I grew up reading Rosemary Sutcliff, Henry Treece and Baroness Orczy. I also admire the audacious writing of Angela Carter, Sarah Waters and Jeanette Winterson, who in various ways have mined the past and the conventions of storytelling to create their own individual worlds of darkness, fakery and magic. (Sarah Waters, who ‘gulls’ the reader in the brilliant ‘Affinity’ was a particular inspiration.)

I think that what attracts me most about historical fiction is the idea that it can take you through a portal into another world – the past – and in that sense it’s like the fantasy books that I also loved as a child, particularly the Narnia series. C.S. Lewis has an exceptional talent for bringing a scene alive, and for making fantastical places seem solid and believable.

I have always loved Shakespeare, and since studying it at school my favourite play has been ‘Macbeth’. Its dark, mysterious atmosphere lingers in the memory, and the three witches wield a preternatural power that is never challenged. But I needed to find a way to tell a story about this play that had a strong female character at its heart. Lady Macbeth herself was my first choice, but I couldn’t make this work.

Then, during my research, I stumbled on a character who has been almost entirely forgotten: Aemilia Bassano Lanyer, the first woman to be published professionally as a poet in England.

Lanyer’s poetry collection ‘Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum’ includes a justification of Eve and a retelling of the Crucifixion from the point of view of the women in the New Testament. Published in 1611, it is dedicated to a roll call of aristocratic women, starting with Queen Anne, the wife of James I. This is the way in which a professional male poet would introduce his work, and Lanyer’s volume is the only surviving example of a woman writing in this way at such an early date.

Lanyer’s poetry collection ‘Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum’ includes a justification of Eve and a retelling of the Crucifixion from the point of view of the women in the New Testament. Published in 1611, it is dedicated to a roll call of aristocratic women, starting with Queen Anne, the wife of James I. This is the way in which a professional male poet would introduce his work, and Lanyer’s volume is the only surviving example of a woman writing in this way at such an early date.The facts of Aemilia Lanyer’s life are dramatic: she was the illegimate child of Jewish immigrant musicians who played at the Tudor court; her father died when she was seven and she was apparently educated at court or in a great house. At seventeen she became the mistress of the Lord Chamberlain, Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon; six years later she was pregnant and married off to a cousin, Alfonso Lanyer, a recorder player who spent her dowry in a year. She later became a client of the astrologer and physician Simon Forman, who talked to her about summoning demons. (Most of these facts have been gleaned from his journal.) And she is one of the women who may have been Shakespeare’s ‘Dark Lady’ the inspiration for the later sonnets.

But who is Shakespeare’s Dark Lady? Was she a real person, or a poetic convention? Opinion has been divided over the years, but the current view is that the sonnets are addressed to real people. However, we don’t know the identity of the Fair Youth (the subject of the earlier sonnets in the sequence) or the Dark Lady, and it’s unlikely that we ever will. In my novel, the Fair Youth is Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, to whom Shakespeare dedicated his poems ‘Venus & Adonis’ and ‘The Rape of Lucrece’. Wriothesley was handsome, impulsive and immensely wealthy which fitted in with my themes.

|

| Henry Wriothesley - image Public Domain |

Shakespeare never used the term ‘Dark Lady’ and both this title and her identity are part of the carefully assembled edifice of pseudo facts that are part of the Shakespeare legend. All we actually have to go on are the plays and poems that survive. The sonnets dedicated to this mysterious woman are anguished and passionate, and suggest that the poet is in the grip of a painful sexual obsession. The myth of the Dark Lady is inspired by the fact that he describes his lover as having black hair and ‘dun’ skin. This was an unfashionable look in Early Modern times: the ideal was fair hair and a pale complexion.

Aemilia Lanyer is one of several candidates for the Dark Lady title, and researchers are continually discovering new possibilities. For example, in 2013 Dr Aubrey Burl, a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, suggested that the Dark Lady was Aline Florio, the wife of an Italian translator. [Link below] Burl put forward eight possible candidates, but chose Aline Florio because she had dark hair and was married, musical, a mother and unfaithful to her husband. (Aemilia Lanyer fits the bill equally well, I have to say.)

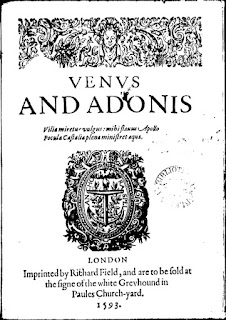

Other candidates who were married to men in Shakespeare’s world include Marie Mountjoy, the wife of Christopher Mountjoy, a costume maker and Shakespeare’s landlord in Silver Street, Jane Davenant, wife to Oxford tavern keeper John Davenant, whose son William, was a prominent figure in the seventeenth century theatre and claimed to be Shakespeare’s son and Jacqueline Field, the wife of Stratford-born Richard Field who printed Shakespeare’s poetry in London. Very little is known about the lives or the characters of these women, and they are possible mistresses primarily because of their proximity to Shakespeare. (For example, it has been suggested that the fact that Field printed Shakespeare’s poetry with such accuracy and attention to detail suggests that Shakespeare had a direct hand in their production, and would therefore have been a frequent visitor to the Field’s print shop.)

|

| Title page printed by Field - image Public Domain |

Lucy Morgan is an interesting candidate, and has inspired both Anthony Burgess and (more recently) Victoria Lamb. Again, there are few surviving facts about her life, but she is thought to have been one of Queen Elizabeth I’s lesser known ladies in waiting, and may also have been the notorious ‘Lucy Negra’, a prostitute in London. If so, her fall was as dramatic as that of Aemilia Lanyer, and the name ‘Negra’ suggests that she was of African descent.

In his 1977 novel ‘Nothing Like the Sun’ Burgess suggests that the relationship between Shakespeare and Lucy is mutually destructive and has tragic consequences for them both. The story is steeped in squalor and disease, and though I went some distance in this direction myself, I couldn’t bear to create a relationship devoid of hope or happiness. However, his novel is truly dazzling in terms of its language and imaginative power.

Mary Fitton and Penelope Devereux were from aristocratic families, and more is known about their lives. Mary Fitton (1578 – 1647) was another of the Queen’s ladies. She had affairs with William Herbert, the Earl of Pembroke (among others) and had children by various men. Herbert was younger than she was, and may be the mysterious ‘Mr WH’ to whom the sonnets are dedicated. Fitton’s relationship with Pembroke was certainly scandalous, and he was sent to the Fleet Prison after Fitton became pregnant with his child. He admitted he was the father, but refused to marry her. More affairs and two marriages followed. Both Frank Harris and George Bernard Shaw make Fitton the Dark Lady in their books, but while Harris suggests that Shakespeare was broken by the relationship, Shaw’s view is that heartbreak was one of his many inspirations.

|

| Mary Fitton - image Public domain |

The most privileged of all possible Dark Ladies is Penelope Devereux (1563- 1607), who became Countess of Devonshire. She was the sister of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, the Queen’s reckless and spoiled favourite, and is also thought to be the inspiration for Stella in Philip Sidney's ‘Astrophel and Stella’ sonnets. Another scandal-prone woman, she married Robert Rich, but had a notorious affair with Charles Blount, Baron Mountjoy, and eventually divorced Rich and married Blount in an unlicensed ceremony. This was a shocking break with canon law, and James I banished them from court. (They were both dead within two years, a sad little footnote to these dramatic events.)

Beautiful and talented, Devereux would have been a glittering figure in the Early Modern cultural scene. She had blonde hair, a point against her perhaps, but dark eyes, and was certainly an inspiration for other poets. If Shakespeare had an affair with her, it would have been a heady and dangerous experience, given her high status in terms of both social class and sexual allure.

So why did I choose Aemilia Lanyer, in the face of such stiff competition? To be honest, I didn’t even know there were so many other candidates until I was well into my first draft. When I discovered that she had existed, a light went on in my head, and I knew that I wanted to write a story about this astonishing person. I was particularly attracted by her status as a poet, and her fall from grace in every other aspect of her life.

One of the themes of my story is ambition and over-reaching – ‘Macbeth’ dramatizes these ideas with great intensity. Aemilia’s own experience is an illustration of this. Early Modern London was a bit like 21st century Hollywood, a place to go and make your fortune and compete for attention. Those who succeeded could gain huge wealth, but there was no safety net for those who failed.

At one point, she was centre stage, a confidante of the Lord Chamberlain, living in close proximity to the Queen herself. What must she have felt, when she was ejected from her suite of rooms in Whitehall Palace? And her home was now a small house in Long Ditch, a narrow street overlooked by some of the great houses of London? I could sense the claustrophobia and panic. And yet, rather than disappearing into the drudgery of domesticity, she wrote her poetry and found a publisher and addressed her work to the greatest women in the land. Five hundred years later, we can still read her words, and hear her voice.

This is fact. From fact comes supposition – suppose she was the Dark Lady? How would she, an aspiring poet, feel about being the subject of these poems? The emotion is undeniable, but they are wracked with pain and spiced with venom. From supposition comes imagination – I decided to try and recreate Aemilia Lanyer in a fusion between fact and fiction, and to tell her the story of her flawed love affair with Shakespeare from her partial and intense point of view.

By doing this, I was able to explore the way in which experience feeds into artistic creation, and rivalry can motivate it. I also wanted to show the obsessive, ruthless aspect of creativity, in which even the worst experiences feed artistic invention. (As Graham Greene said, there is a splinter of ice in the heart of every writer.) The relationship between Shakespeare and Lanyer is more than just an anguished love affair, it is a battle of wills and a clash of egos. In that sense, I felt that her story could be an inspiration for every writer who has struggled to be heard, and for every woman who resists the constraints of convention and domesticity.

Salve Deus - author: Author usage licensed: Creative Commons

Burl's Article

[This article is an Ediotrs' Choice post, which originally appeared on 28th March, 2014]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

‘Dark Aemilia’ is published by Myriad Editions on March 27th and by Picador US in June.

Sally O’Reilly is the author of How to be a Writer and two contemporary novels The Best Possible Taste and You Spin Me Round both published by Penguin. Her short stories have appeared in the UK, Australia and South Africa. She worked as a journalist and editor for Christian Aid and Barnardo’s, and has freelanced for the Guardian, Sunday Times, Evening Standard and New Scientist. Sally has a PhD in Creative Writing from Brunel University and teaches Creative Writing at the Open University. Dark Aemilia is her first historical novel.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting even to one not much interested in the time period. I hadn't heard of all those candidates for the honor of being the dark lady though I did read an essay someplace and sometime in which it was suggested that the lady was no lady at all. The descriptions of the women make them individuals. I admire talent.

ReplyDeleteVery convincing argument for writing about Aemilla, Sally! This isn't about who the Dark Lady actually was, but what she represents and how you can use the story (and real poetry too!) to address universal themes. Well done and good luck!

ReplyDelete