On Thursday 26th October 1396 King Richard II travelled to France with a vast contingent of family, counsellors and English nobility, as well as a huge personal wardrobe, to take a new wife. It was two years since the death of Anne of Bohemia and Richard was without an heir, a dangerous position for a medieval state. At thirty years of age, it was essential that he marry again. For Richard, however, the need for an heir would not appear to be his first priority, for his new bride was not quite seven years old.

(To overcome the immediate problem, Richard was to select his cousin Edward, Earl of Rutland, as his 'brother' and heir, giving him the title Duke of Aumale.) Here is Richard II, splendid in red with gold lions, receiving a copy of Froissart's Chronicles from the author.

(To overcome the immediate problem, Richard was to select his cousin Edward, Earl of Rutland, as his 'brother' and heir, giving him the title Duke of Aumale.) Here is Richard II, splendid in red with gold lions, receiving a copy of Froissart's Chronicles from the author.But back to the marriage. Richard met with Charles VI of France (in one of his saner moments) at Ardres in France where a truce in the 100 Years War was hammered out between the two countries. For England a truce was more advantageous than a full peace treaty which would have demanded greater concessions from England. It was not a popular marriage in England but Richard saw it as an occasion on which to make his presence known on the European scene.

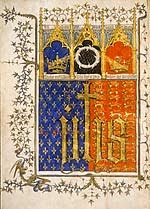

The poet and author Philippe de Mezieres gave Richard a beautifully illuminated manuscript, the Letter to King Richard, extolling the value of the marriage and exhorting Richard to go on Crusade, sending it to Richard from Paris on behalf of Charles VI in advance of the marriage. Here is one of the superb illuminated pages.

The poet and author Philippe de Mezieres gave Richard a beautifully illuminated manuscript, the Letter to King Richard, extolling the value of the marriage and exhorting Richard to go on Crusade, sending it to Richard from Paris on behalf of Charles VI in advance of the marriage. Here is one of the superb illuminated pages.Richard was persuaded; he never took up the idea of the Crusade but the marriage appealed to him, seeing an opportunity to win affection and good will from his subjects when there would be no further drain on the treasury for campaigns that brought little benefit. Furthermore he could make an superlative impression of wealth and power in Europe.

Once the truce was decided on, it was time to discuss Isabelle's dowry and the terms of her marriage. Her dowry was fixed at 800, 000 francs, 300,000 to be paid on the occasion of the marriage and the rest in annual instalments. If Richard were to die childless before her twelfth birthday, the youngest age at which Isabelle might be considered to be physically mature to fulfil her role as wife, she was to have 500,000 francs for her own disposal. Interestingly, on her twelfth birthday Isabelle would have the power to refuse consent to this marriage if she so wished, as Richard would have the right to reject her. In the event of Richard's death, Isabelle would be free to return to France with this money and all her jewellery.

A great encampment of pavilions was set up near Ardres in France and it was to this that Richard came. On the following day the kings met, Richard in long scarlet gown bearing his own livery of the white hart, Charles clothed in similar fashion, but shorter, emblazoned - a nice touch here - in memory of Richard's late queen. All was splendour and magnificence. Richard gave Charles a collar of pearls and precious stones, belonging to Anne of Bohemia, worth 5,000 marks. Many of the English royal family present - the Duchess of Lancaster, Countess of Huntingdon and Joan Beaufort - were given solid gold livery chains to wear, bearing the white hart. There was much festivity: wine and sweetmeats, kisses and handclasps, with banquets and junketing that went on for four days.

Comparisons have been made with the later Field of the Cloth of Gold, as shown here, between Henry VIII and Francis I, the two monarchs lavish with their gifts and good will and promises of eternal friendship, all set about with banquets and dances and lavish spectacle, but with one main difference. Henry and Francis jousted regularly. Richard and Charles did not. Neither of them had the physical attributes or love of physical sport of the later monarchs.

All this cost Richard a vast amount of money, but for him it was worth it. This was power play at the highest level, his first ever meeting with another king, where he must not be found wanting. No expense was spared, Richard having to borrow to offset his spending estimated between £10,000 and £15,000. A torrential downpour during the proceedings which soaked many of the lords and swept away some of the French pavilions did nothing to dampen his enthusiasm for the marriage.

Finally the little bride was delivered to Richard on the 30th October. She had a French governess, Madame de Courcy, but was was entrusted in England to the care of the Duchesses of Lancaster and Gloucester and the Countesses of Huntingdon and Stafford. Richard and Isabella were married on 4th November in the church of St Nicholas in Calais.

What of Isabelle's thoughts on this marriage? Did she, at six years old, enjoy leaving family and those known to her to go to live in England, with a husband she had never before met? We have no idea. Richard seems to have treated her with much affection, rather like a sister in the brief three years of their marriage.

As for the jewels in Isabelle's dowry, we know in some detail what she brought with her. It must have been a remarkable collection of crowns and chaplets, collars and brooches and jewelled clasps, gold and silver vessels for use in her apartments and chapel. Even her dolls were packed up for her to bring to England along with their miniature silver furnishings.

As for the jewels in Isabelle's dowry, we know in some detail what she brought with her. It must have been a remarkable collection of crowns and chaplets, collars and brooches and jewelled clasps, gold and silver vessels for use in her apartments and chapel. Even her dolls were packed up for her to bring to England along with their miniature silver furnishings.The marriage was brief and tragic for Isabelle. After Richard's imprisonment and death, she remained in England, a pawn in a political game, in spite of her father's demands that she return home, because Henry IV could not afford to repay Isabelle's dowry. The French ambassadors had difficulty in gaining access to her. She sailed at last for France in August 1401 where she eventually married her cousin Charles Duke of Orleans, but there was little happiness for her as she died in childbed in 1409 at the age of 19 years.

The marriage treaty between Richard and Isabelle had stipulated that if the marriage was unconsummated, Isabelle's dowry and jewels should be returned to France with her. The dowry received was never repaid (Henry IV continued to have his own financial problems) but almost all the jewels and plate returned with her in 1401. The rich array of gifts, however, sent to the happy couple by King Charles and Queen Isabeau, as well as by Isabelle's two uncles the Dukes of Burgundy and Berry, were never returned. They could still be found in the possession of the Lancastrian kings in the 15th century, doubtless a pragmatic move on the part of Henry IV.

So what do we say about Isabelle, Queen of England? One of those brief, transient lives about which we know so little. A prime example of the importance of royal daughters in the medieval marriage stakes, where personal happiness of a young girl weighed nothing against the demands of state connections and political alliance. All in all, not a happy story.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

www.anneobrienbooks.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.