by Mike Rendell

Had you been around in London on 16th November in 1724 there is a one in four chance that you would have been in the procession (some two hundred thousand strong) wending its way in a carnival atmosphere towards Tyburn Hill, where the empty gallows were being prepared for a hanging. One in four, because the crowd represented at least a quarter of the capital’s population at the time, and they were all there to ‘honour’ one man: the diminutive Jack Sheppard.

Daniel Defoe is presumed to have been hard at work scribbling the final touches to a biography which was on sale ‘hot from the press’ by the time of the execution. And the 22-year-old Jack, his cart escorted by uniformed guards, paused long enough at the City of Oxford Tavern in Oxford Street to sink a pint of sack (sherry), no doubt bemoaning the fact that one of his prison guards had discovered a pen-knife secreted about his person, and thereby scotched his chance of escape. And escaping was what Jack was good at, and why the crowds turned out in their thousands.

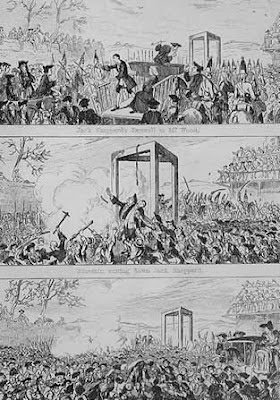

The series of three scenes shown above are from“The Last Scene”engraved by George Cruikshank in 1839, over a hundred years after Sheppard died, to illustrate the serialised novel, 'Jack Sheppard' by William Harrison Ainsworth.

For there was no doubt that the baby-faced Jack Sheppard was a thief, and was getting his just rewards from a legal system designed to protect the wealthy. But over and over again he had escaped justice with his daring escapes, and no doubt the throng wanted to see if he could pull off the final escape, the big one, from Death itself. There was to be no such luck, and the lad finally went to meet his Maker that day nearly three centuries ago.

Sheppard had been born in 1702 into abject poverty in the deprived area of Spitalfields: his father died when he was young and his mother had little choice but to send him to the Workhouse when he was six years old. Jack was lucky - eventually he was placed with a draper on The Strand called William Kneebone, as a shop-boy. Kneebone took the lad under his wing, taught him the rudiments of reading and writing and encouraged him to become apprenticed as a carpenter (a seven year indenture, which was signed in 1717 when Jack was 15). His master was Owen Wood, whose premises were in Covent Garden.

All went well for five years – an exemplary pupil, who showed every aptitude for carpentry and hard work. Then, well, he went off the rails. Maybe it was too many visits to The Black Lion off Drury Lane; maybe it was the blandishments of the young whore Elizabeth Lyon (otherwise known as Edgeworth Bess) whom he met there; or maybe it was the company he fell into while frequenting the establishment, and in particular the notorious Joseph ‘Blueskin’ Blake or the duplicitous Jonathan Wild (who styled himself the Thief-Taker General, though in reality he was a thief himself, but one who turned in his acquaintances whenever it was opportune to do so).

Whatever the reason, the fact was – young master Jack turned himself to a life of petty crime, and soon there was no way back. For a while it was pilfering – helping himself to odds and ends from people’s houses while on carpentry errands. But by 1723 he had jacked in his apprenticeship, and set up home with Mistress Bess.

Naturally she wanted to be spoiled rotten; naturally she was not content with the proceeds of minor shop lifting; she wanted Jack to show her the good life. He turned to burglary ( an offence which carried the death penalty). Mistress Bess was arrested after they had moved to Piccadilly from Fulham: Jack broke in to the jail and rescued her!

Jack and his brother Tom, aided by Bess, embarked on a series of robberies until Tom got caught. The previous year he had also been apprehended (and suffered the painful penalty of being branded on the hand). This time he shopped his brother Jack to save his own skin, and a warrant for Jack’s arrest was issued.

Knowing this, and anxious to get his hands on the forty pounds offered as a bounty, Jonathan Wild betrayed Jack to the constables and he was arrested and locked up in the very prison from which he had rescued Elizabeth. Within hours of his incarceration he had cut a hole in the ceiling (leg irons notwithstanding) climbed on to the roof and dropped down to join a crowd who had gathered when news of his escape became known. Diverting attention by announcing that he could ‘see someone on the roof over there’ he calmly shuffled off in the opposite direction…

In May 1724 Jack was arrested for a second time – caught while in the act of lifting a pocket-watch from a gentleman in what is now Leicester Square, and was taken off to Clerkenwell prison, where he was locked up with his mistress. A few days passed while Jack, active with a file, cut through the manacles which chained them both, and then removed one of the iron bars on the prison window. He lowered himself and his buxom Bess down to the street on a knotted bed-sheet (no mean feat given his lack of stature) and off they went into the darkness.

Things escalated – they tried their hand at highway robbery and burglary, stooping so low as to break into the home of his old employer and helper William Kneebone, but the greedy Jonathan Wild was closing the trap. He found Elizabeth Lyon, plied her with alcohol to loosen her tongue, and by this means established where Jack was staying.

Again he was arrested, again he was sent to prison (this time to the notorious Newgate), and guess what, he escaped from there as well! On 30th August a warrant for his death was being brought to the prison from Windsor – but by the time it arrived it was discovered that Jack had escaped. Aided and abetted by Bess he had removed one of the window bars, dressed in female clothing brought into prison by his accomplice, and made good his escape via boat up the river to Westminster.

By now he was renowned for his escapades. He was every cockney’s hero, Jack the Lad whom no bars could hold. After all, he hadn’t killed anyone, he was the ultimate cheeky chappy who always got away from the law in the nick of time. Added to that he was good looking in a baby-faced sort of way, young, strong and very agile. This was the stuff of which legends would be made…

Jack lay low for a few days but was soon back to his old tricks, and on 9th September was captured and returned to the condemned cell at Newgate, His fame meant that he was visited by the great and the good – gawpers who wanted to say that they had met Jack Sheppard. All this time he was not just in leg-irons, but chained to iron bolts in the floor of the cell.

Cheekily he had demonstrated to his guards his ability to pick the padlocks with a bent nail, and they in turn had increased the security by having him not just hand-cuffed but bound tightly as well. Having trussed him up like a turkey, they retired for the night…. and Jack set to work.

He couldn’t get rid of the leg-irons but he could free himself from the other restraints. He managed to break into the chimney, where his pathway was blocked by an iron bar. This he dislodged, using it to break a hole in the ceiling and as a crow bar to open various doors barring his way. At one point he went back to his cell to retrieve his bed clothes, as he needed these to drop down on to the roof of a building next to the prison. He waited until midnight, let himself into the building via the roof, and calmly walked out the front door (still in his leg-irons).

The lad must have had a fair amount of chutzpah, because after lying low for a couple of days he was able to persuade a passer-by that he had been imprisoned elsewhere for failing to maintain an illegitimate son – and would he mind fetching some smithy tools? The passer-by obliged and within a few hours Jack had broken his fetters, and was off to taste a freedom which was to last all of a fortnight.

It was at this point that the journalist Daniel Defoe was brought in to pen Jack’s story, which he did anonymously as The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard.

On the night of 29th October Jack Sheppard broke in to a pawnbrokers shop in Drury Lane, helping himself to a smart black silk suit, a silver sword, rings, watches, a peruke wig, and other items. He then hit the town, dressed in style, and passed the next day and a half drinking and whoring. Finally, in a drunken torpor, he was arrested on 1st November, dressed “in a handsome Suit of Black, with a Diamond Ring and a Cornelian ring on his Finger, and a fine Light Tye Peruke”.

Back he was taken to Newgate, imprisoned in an internal room and weighted down with iron chains. His celebrity status meant that he was visited by the rich and famous, and had his portrait painted by James Thornhill, painter to his Majesty King George I.

There was a clamour for his release but the authorities were adamant: Jack must pay the price for his notoriety. And so it was that on 16th November 1724 a huge and happy crowd escorted Jack to the gallows, where he did what prisoners were supposed to do – hang. After a quarter of an hour he was cut down, rescued from any attempt by the vivisectionists to claim his body, and buried in the churchyard at St Martin’s-in-the-Fields.

That was the end of Jack Sheppard but not the end of his story. Pamphlets, books and plays were written, all singing the praises of this swash-buckling hero. His name quickly became an icon and his story inspired John Gay to write The Beggar’s Opera in 1728. It was hugely popular.

Others piled into print and for the next one hundred years the tales based on Jack’s exploits were legion. It got so bad that at one stage the Lord Chancellor’s office banned the production of any plays containing Jack Sheppard’s name in the title – for over forty years – for fear that it would encourage lawless behaviour.

Let us remember Jack Sheppard – a twenty-two year old who went to the gallows for offences which today would merit little more than a slap on the wrist or a spell in a Young Offenders Institutiion. The boy did wrong, but his memory lives on in our collective consciousness, kept alive by every tale of “the lovable Cockney rogue” and every mention of behaviour being that of “Jack the Lad”.

(Mike is the author of The Journal of a Georgian Gentleman, a social history of England in the 18th Century as seen through the eyes of his ancestor Richard Hall. The book is currently being reprinted but you can follow Mike on his blogsite here.)

Had you been around in London on 16th November in 1724 there is a one in four chance that you would have been in the procession (some two hundred thousand strong) wending its way in a carnival atmosphere towards Tyburn Hill, where the empty gallows were being prepared for a hanging. One in four, because the crowd represented at least a quarter of the capital’s population at the time, and they were all there to ‘honour’ one man: the diminutive Jack Sheppard.

Daniel Defoe is presumed to have been hard at work scribbling the final touches to a biography which was on sale ‘hot from the press’ by the time of the execution. And the 22-year-old Jack, his cart escorted by uniformed guards, paused long enough at the City of Oxford Tavern in Oxford Street to sink a pint of sack (sherry), no doubt bemoaning the fact that one of his prison guards had discovered a pen-knife secreted about his person, and thereby scotched his chance of escape. And escaping was what Jack was good at, and why the crowds turned out in their thousands.

The series of three scenes shown above are from“The Last Scene”engraved by George Cruikshank in 1839, over a hundred years after Sheppard died, to illustrate the serialised novel, 'Jack Sheppard' by William Harrison Ainsworth.

For there was no doubt that the baby-faced Jack Sheppard was a thief, and was getting his just rewards from a legal system designed to protect the wealthy. But over and over again he had escaped justice with his daring escapes, and no doubt the throng wanted to see if he could pull off the final escape, the big one, from Death itself. There was to be no such luck, and the lad finally went to meet his Maker that day nearly three centuries ago.

Sheppard had been born in 1702 into abject poverty in the deprived area of Spitalfields: his father died when he was young and his mother had little choice but to send him to the Workhouse when he was six years old. Jack was lucky - eventually he was placed with a draper on The Strand called William Kneebone, as a shop-boy. Kneebone took the lad under his wing, taught him the rudiments of reading and writing and encouraged him to become apprenticed as a carpenter (a seven year indenture, which was signed in 1717 when Jack was 15). His master was Owen Wood, whose premises were in Covent Garden.

All went well for five years – an exemplary pupil, who showed every aptitude for carpentry and hard work. Then, well, he went off the rails. Maybe it was too many visits to The Black Lion off Drury Lane; maybe it was the blandishments of the young whore Elizabeth Lyon (otherwise known as Edgeworth Bess) whom he met there; or maybe it was the company he fell into while frequenting the establishment, and in particular the notorious Joseph ‘Blueskin’ Blake or the duplicitous Jonathan Wild (who styled himself the Thief-Taker General, though in reality he was a thief himself, but one who turned in his acquaintances whenever it was opportune to do so).

Whatever the reason, the fact was – young master Jack turned himself to a life of petty crime, and soon there was no way back. For a while it was pilfering – helping himself to odds and ends from people’s houses while on carpentry errands. But by 1723 he had jacked in his apprenticeship, and set up home with Mistress Bess.

Naturally she wanted to be spoiled rotten; naturally she was not content with the proceeds of minor shop lifting; she wanted Jack to show her the good life. He turned to burglary ( an offence which carried the death penalty). Mistress Bess was arrested after they had moved to Piccadilly from Fulham: Jack broke in to the jail and rescued her!

Jack and his brother Tom, aided by Bess, embarked on a series of robberies until Tom got caught. The previous year he had also been apprehended (and suffered the painful penalty of being branded on the hand). This time he shopped his brother Jack to save his own skin, and a warrant for Jack’s arrest was issued.

Knowing this, and anxious to get his hands on the forty pounds offered as a bounty, Jonathan Wild betrayed Jack to the constables and he was arrested and locked up in the very prison from which he had rescued Elizabeth. Within hours of his incarceration he had cut a hole in the ceiling (leg irons notwithstanding) climbed on to the roof and dropped down to join a crowd who had gathered when news of his escape became known. Diverting attention by announcing that he could ‘see someone on the roof over there’ he calmly shuffled off in the opposite direction…

In May 1724 Jack was arrested for a second time – caught while in the act of lifting a pocket-watch from a gentleman in what is now Leicester Square, and was taken off to Clerkenwell prison, where he was locked up with his mistress. A few days passed while Jack, active with a file, cut through the manacles which chained them both, and then removed one of the iron bars on the prison window. He lowered himself and his buxom Bess down to the street on a knotted bed-sheet (no mean feat given his lack of stature) and off they went into the darkness.

Things escalated – they tried their hand at highway robbery and burglary, stooping so low as to break into the home of his old employer and helper William Kneebone, but the greedy Jonathan Wild was closing the trap. He found Elizabeth Lyon, plied her with alcohol to loosen her tongue, and by this means established where Jack was staying.

Again he was arrested, again he was sent to prison (this time to the notorious Newgate), and guess what, he escaped from there as well! On 30th August a warrant for his death was being brought to the prison from Windsor – but by the time it arrived it was discovered that Jack had escaped. Aided and abetted by Bess he had removed one of the window bars, dressed in female clothing brought into prison by his accomplice, and made good his escape via boat up the river to Westminster.

By now he was renowned for his escapades. He was every cockney’s hero, Jack the Lad whom no bars could hold. After all, he hadn’t killed anyone, he was the ultimate cheeky chappy who always got away from the law in the nick of time. Added to that he was good looking in a baby-faced sort of way, young, strong and very agile. This was the stuff of which legends would be made…

Jack lay low for a few days but was soon back to his old tricks, and on 9th September was captured and returned to the condemned cell at Newgate, His fame meant that he was visited by the great and the good – gawpers who wanted to say that they had met Jack Sheppard. All this time he was not just in leg-irons, but chained to iron bolts in the floor of the cell.

Cheekily he had demonstrated to his guards his ability to pick the padlocks with a bent nail, and they in turn had increased the security by having him not just hand-cuffed but bound tightly as well. Having trussed him up like a turkey, they retired for the night…. and Jack set to work.

He couldn’t get rid of the leg-irons but he could free himself from the other restraints. He managed to break into the chimney, where his pathway was blocked by an iron bar. This he dislodged, using it to break a hole in the ceiling and as a crow bar to open various doors barring his way. At one point he went back to his cell to retrieve his bed clothes, as he needed these to drop down on to the roof of a building next to the prison. He waited until midnight, let himself into the building via the roof, and calmly walked out the front door (still in his leg-irons).

The lad must have had a fair amount of chutzpah, because after lying low for a couple of days he was able to persuade a passer-by that he had been imprisoned elsewhere for failing to maintain an illegitimate son – and would he mind fetching some smithy tools? The passer-by obliged and within a few hours Jack had broken his fetters, and was off to taste a freedom which was to last all of a fortnight.

It was at this point that the journalist Daniel Defoe was brought in to pen Jack’s story, which he did anonymously as The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard.

On the night of 29th October Jack Sheppard broke in to a pawnbrokers shop in Drury Lane, helping himself to a smart black silk suit, a silver sword, rings, watches, a peruke wig, and other items. He then hit the town, dressed in style, and passed the next day and a half drinking and whoring. Finally, in a drunken torpor, he was arrested on 1st November, dressed “in a handsome Suit of Black, with a Diamond Ring and a Cornelian ring on his Finger, and a fine Light Tye Peruke”.

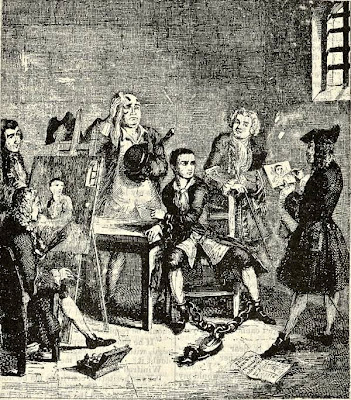

Back he was taken to Newgate, imprisoned in an internal room and weighted down with iron chains. His celebrity status meant that he was visited by the rich and famous, and had his portrait painted by James Thornhill, painter to his Majesty King George I.

There was a clamour for his release but the authorities were adamant: Jack must pay the price for his notoriety. And so it was that on 16th November 1724 a huge and happy crowd escorted Jack to the gallows, where he did what prisoners were supposed to do – hang. After a quarter of an hour he was cut down, rescued from any attempt by the vivisectionists to claim his body, and buried in the churchyard at St Martin’s-in-the-Fields.

That was the end of Jack Sheppard but not the end of his story. Pamphlets, books and plays were written, all singing the praises of this swash-buckling hero. His name quickly became an icon and his story inspired John Gay to write The Beggar’s Opera in 1728. It was hugely popular.

Others piled into print and for the next one hundred years the tales based on Jack’s exploits were legion. It got so bad that at one stage the Lord Chancellor’s office banned the production of any plays containing Jack Sheppard’s name in the title – for over forty years – for fear that it would encourage lawless behaviour.

|

| Courtesy of East London Theatre Authority. |

Let us remember Jack Sheppard – a twenty-two year old who went to the gallows for offences which today would merit little more than a slap on the wrist or a spell in a Young Offenders Institutiion. The boy did wrong, but his memory lives on in our collective consciousness, kept alive by every tale of “the lovable Cockney rogue” and every mention of behaviour being that of “Jack the Lad”.

|

| A mezzotint engraving, after the Thornhill portrait mentioned above. |

(Mike is the author of The Journal of a Georgian Gentleman, a social history of England in the 18th Century as seen through the eyes of his ancestor Richard Hall. The book is currently being reprinted but you can follow Mike on his blogsite here.)

I really enjoyed reading about Jack--thank you!

ReplyDeleteMy pleasure! It is the extraordinary way 18th Century justice punished crimes against property as severely as crimes against the person which amazes me. Jack was a likeable rogue who deserved a short sharp shock such as a spell in the pillory,with people throwing rotten apples at him, not a sentence of death!

ReplyDeleteIs there a movie about this? Would surely watch it. The story is already great even though it's just narrated here. It'll be more interesting if its in the movie.

ReplyDeleteI am not aware of a movie. I suspect Hollywood would make our hero a 6-foot tall swash-buckling lothario who could charm his way out of prison, as opposed to a rather puny young lad who craved notoriety and whose wrists were too small for normal handcuffs ....

ReplyDeleteStanley Baker's "Where's Jack?", starring Stanley Baker as Jonathan Wild, Fiona Lewis as Elizabeth Lyon (Edgeworth Bess) and Tommy Steele as Jack - released in 1969. It's only a fictional romantic caricature of what happened. Historically inaccurate, but an entertaining watch nonetheless.

ReplyDeleteI'm heading to London in May and interested in looking up anything about Jack.

ReplyDeleteMy grandfather moved to Canada from England around 1908 and his name was also Jack Sheppard. Our family name has the same spelling which is one of the less common spellings, so I wonder if we're related somewhere along the line.

Thanks for the interesting article.

Robert Sheppard

I love my English history, And being of a certain age! OLD...Lol... I'm ashamed of myself for not knowing about Jack Shepherd until I watching the news today... Now I'm fascinated and want to know more..Thank you for this .

ReplyDelete