by Maggi Andersen

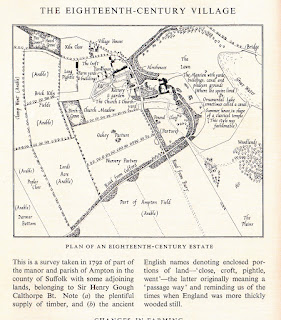

The spread of this system encouraged experiments in new methods of planting and tilling which were gradually supplanting the old medieval ways. Much of the country still practiced the old medieval ‘open field’ system in which each man who held land was given ‘strips’ divided from those of other by ridges of earth. But the enclosing of land by hedges had notably increased since the sixteenth century, and was by now prevalent among the farmers of south-eastern and south-western England. It was seen to produce such good results that the practice became general. It was frequently legalized by the passing of Enclosure Acts by Parliament, enforcing the enclosure of special tracts of country. The land was then re-divided; each tenant had his own fields in one locality and cut them off from those of his neighbors by neat hedges.

~~~~~~~

Maggi Andersen is a USA TODAY bestselling author of Regency romance. She fell in love with the Georgian and Regency eras after reading the books of Georgette Heyer and Jane Austen, and the Victorian era through the works of the Bronte sister’s and Gothic stories of Victoria Holt. After gaining a BA and an MA in Creative Writing Maggi began a career in writing. She lives with her husband in the beautiful Dandenong ranges of Australia.

Author website

Farming was the chief occupation in Britain, until the invention of machinery changed her from an agricultural into an industrial nation. The change was not completed until the early nineteenth century, by which time Britain’s population had increased so enormously that it could not in any case have been fed by home-grown produce alone. Meanwhile the eighteenth century had brought tremendous developments of agriculture.

The advantages of this were:

Improvements in treating the soil could now be more generally tried and their results noted.

Time wasted in getting from one separated strip of a man’s holding to another was saved.

The industrious farmer had less to fear from invasion by his neighbor’s weeds.

Cattle diseases were more easily kept in check when a farmer could enclose his pasture land and keep out other men’s herds.

The disadvantages:

Most big reforms involve hardship. The poor landless laborer accustomed to gather firewood or pasture his beast on the open common, found it closed against him. The yeoman who farmed in a small way could be ousted by the man able to afford the rent of a large enclosed farm. Yet evidence seems to show that the number of small farmers increased rather than diminished during this enclosure period, and the new agricultural methods must have provided plenty of employment. Rural life suffered when villagers migrated to the town, attracted by the relatively high wages offered.

New methods were found to improve the quality of the soil reclaiming previously unproductive land for the growing of crops. This was done by draining away superfluous moisture, and sometimes by altering the substance of the soil, e.g. mixing chalk and clay with thin, sandy soil.

In 1701 a Berkshire man, Jethro Tull, invented the ‘drill’, a machine for sowing seeds in regular rows instead of wastefully scattering them by hand. He also encouraged the use of the hoe.

New crops such as turnips, cleansed the soil for the next year’s crop of barley or wheat, so that it was not necessary to let each field lie fallow for one year in turn. These root crops could be fed to the cattle in winter when there was very little winter fodder. More fresh meat now became available.

Beginning first with the wealthy landowners, these methods became universally practiced. King George III himself set up a model farm at Windsor, and made breeding of fine cattle a fashionable hobby among the rich.

Lord Townshend (1674-1738), friend and colleague of Walpole, was a rich landowner who grew root-crops on a large scale – hence his nickname of ‘Turnip Townshend.’

Thomas Coke (1752-1842) was a rich landlord who inherited his Norfolk estates in bad condition, the sheep were of a poor breed and all the fields were open. Coke farmed it himself instead of renting it, inviting other farmers from the district to inspect his farm and advise him. He improved the soil and was eventually able to grow wheat successfully where no one had ventured to plant anything but rye. He increased the number of his cattle and sheep, improved their quality and provided better farm buildings and cottages for his workmen.

Robert Bakewell (1725-95) was a pioneer in the breeding of a good livestock. He became famous for his new breed of sheep known as ‘Leicesters’ which grew fat and matured more quickly than others. His ideas were copied and sheep were made twice as valuable for their meat as well as their wool. His new ‘Leicestershire longhorn’ cattle were equally notable.

Source: British History Displayed 1688-1950

Maggi Andersen is a USA TODAY bestselling author of Regency romance. She fell in love with the Georgian and Regency eras after reading the books of Georgette Heyer and Jane Austen, and the Victorian era through the works of the Bronte sister’s and Gothic stories of Victoria Holt. After gaining a BA and an MA in Creative Writing Maggi began a career in writing. She lives with her husband in the beautiful Dandenong ranges of Australia.

Author website

Interesting post, Maggi. I love learning about anything in the 18th century, the era which I research for my novels.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the post Maggi! Very informative! I enjoy your posts.

ReplyDeleteThanks Suzan. I'm glad you enjoyed it.

DeleteI second, Suzan! Very informative and enjoyable. Thanks for sharing, Maggi!

ReplyDeleteThanks Lucinda!

DeleteSo, is the notion that the enclosures force people off the land and into the towns something of a folk myth?

ReplyDeleteMany years ago i read the excellent 'Ulverton' by Adam Thorpe which chronicled village life over 4 centuries, including the 18th. My view is there are more than enough 18C set novels about the lives of the monied and the landed and not nearly enough about the common folk.

Industrialization was the major force behind the exodus to the cities. There aren't many novels I know of. There's Thomas Hardy in the 19th C of course. I'll look out for Ulverton, thanks.

ReplyDelete