|

| The 4th Baron Mohun |

His father had inherited substantial lands in Cornwall and Devon--as well as considerable debts. The marriage to Lady Phillipa was entirely mercenary, she was a termagant, and the union neither prospered nor lasted. Shortly after his heir's birth, the 3rd Baron served as Lord Cavendish's second in a duel with an Irish officer. At the conclusion of the contest Mohun insulted his friend's opponent, resulting in a second swordfight, and the brawling baron died from his severe wounds.

The infant 4th Baron and his two-year old sister Elizabeth were left to the care of a cruel, careless, and quarrelsome mother. His upbringing was hardly the sort to bestow virtue, patience, and manners. Unlike most young men of noble birth, he did not attend university. He married in 1691, aged just fifteen. His bride was Charlotte Orby, his guardian's daughter and the niece of his close friend Lord Macclesfield, and she had no dowry. In November of 1692 she bore a stillborn son.

Several weeks after this distressing event, the sixteen-year old baron fought his first duel. After a night of drinking he quarreled with Lord Kennedy, four years his senior. King William III, hearing of it, feared that a duel might ensue, and commanded both young gentlemen to remain at home. They chose not to obey their monarch's edict. In the course of their battle, each received a minor wound.

Two days later Mohun assisted his closest friend, the equally wild Captain Richard Hill, in the failed abduction of the actress Mrs Bracegirdle. Hill, who regarded actor William Mountfort as his rival for the lady's affection--quite mistakenly--ran him through with a sword late at night in the middle of a London residential street. Hill fled the country. Mohun was arrested. His response: 'Goddamme, I am glad he's not taken, but I am sorry he has no money about him, I wish he had some of mine. I do not care a farthing if I hang for him.'

The magistrates charged him with murder but after a single night in jail his bail was paid and he was released. Judged a flight risk by the House of Lords, he was confined to the Tower of London to await his fate.

In a sensational trial, the House of Lords tried the baron as an accessory to the crime, and in February 1693 he was acquitted and released. Either the weeks of his imprisonment impaired his health, or his celebrations after gaining his freedom, because by October that year it was reported that he 'lies very ill at Bath.' Mountford's outraged widow attempted to appeal what was, from her perspective, a most unjust verdict. Her father had recently been convicted of a capital crime--clipping coins--and by dropping her intended action she was able have her parent sentenced to transportation rather than execution.

Recovered from his ailment and back in London, Mohun returned to form. Drawing his sword against a hackney coachman, he was prevented from slaying the man by a member of Parliament, whom he then challenged to a duel which never actually took place.

Deciding to use his fighting instincts in the service of king and country, he joined the military. On March 10, 1694 the diarist Luttrell records, 'The Lord Mohun is made a captain of a troop of horse in Lord Macclesfield's [sic] regiment.' Three days later he noted, 'The Earl of Macclesfield goes with his majestie to Flanders, as a major general, and the Earl of Warwick and Lord Mohun as volunteers.' Warwick was one of Mohun's cronies, a partner in drinking and debauchery.

Whatever discipline the baron absorbed in the ranks, it didn't improve his behaviour. In spring 1695, he battered a member of the press in a London coffee house. Two years later his next duel took place in St James's Park. His opponent, Captain Bingham, survived the encounter--park keepers intervened--and Mohun sustained a wound to his hand.

In September of that same year, 1697, at the Rummer Tavern in Charing Cross, he engaged in a drunken quarrel with a Captain Hill. This was not the perpetrator of the Mountford murder, but another of that name and rank serving in the Coldstream Guards. Mohun stabbed him and fled; the captain later died. Mohun took refuge in the Earl of Warwick's house, where the constables seized him. At the coroner's inquest he was judged guilty of manslaughter.

According to a contemporary account, 'Yesterday [27th November] the lord Mohun appeared upon his recognizance at the King's Bench bar, and there being an indictment of murther found against him by the grand jury of Middlesex for killing Capt Hill, the court committed him to prison in order to be tryed for the same.' His place of confinement was not to his liking or suitable to his status, and on the 13th of December 'the lord Mohun petitioned the house of peers to be removed from the King's Bench where he was committed last term for the murder of Captain Hill, to the Tower, which was granted.'

This time, however, he avoided trial--most likely because he'd reached his majority. Now twenty-one, he was entitled to take his seat in the House of Lords, and the King needed his support. At the 11th hour he received a royal pardon, which he duly presented to the House. Within days he was seated with his fellow peers as a Whig lord with good reason to approve all of His Majesty's demands for additional war funding.

Never one to learn from past crimes, Mohun committed another in late October of the very same year:

On Sunday about 3 in the morning a quarrel happened at Locket's [a tavern] near Charing Crosse between Captain Coot [sic] son to Sir Richard Coot, and Mr French of the Temple, who thereupon went and fought in Leicester Feilds. The Earl of Warwick and Lord Mohun were for the first, and Captain James and Ensign Dockwra for the 2d. Coot was killed upon the spott, and it's said French dangerously wounded but made his escape with the rest.

The House chose to try Mohun and Warwick separately, but it was uncertain which of the five men present at the altercation had struck the fatal blow. In January Mohun returned to the Tower to await trial and remained there for several months. On 28th March, 1699, 'the earl of Warwick and lord Mohun were brought by the lord Lucas from the Tower to Westminster the axe being carried before them they are now on their tryalls on account of the death of captain Coot [sic] which is like to last long.' On that day the earl was convicted of manslaughter and given the mildest of punishments: a cold branding iron in the shape of 'F' for 'felon' was applied to his hand, leaving no permanent mark upon it. The following day Mohun was unanimously acquitted but received a severe warning from Lord Chancellor Somers that he could not expect mercy in future if he continued on his disastrous path.

In 1701 the Act of Settlement designated the Protestant Sophia, Electress of Hanover, and her heirs as William III's successors to England's crown. Lord Macclesfield was the King's choice to deliver a ceremonial copy of the decree, and Lord Mohun accompanied him to Hanover. Within days of their return to London, Mohun stood at his gravely ill friend's bedside. The earl's death on 4th November was followed by the discovery that he'd disinherited his entire family in Mohun's favour.

|

| James, 4th Duke of Hamilton |

In 1711, Mohun, by then a widower, took his mistress as his second wife. She was Elizabeth Griffith, widow of a colonel and a daughter of Sir Thomas Lawrence, a physician to the Queen. He had hardly installed her in his residence, Macclesfield House, than he departed it to take up lodgings in Great Marlborough Street.

Not until 8th February, 1712, was his inheritance dispute with Hamilton heard by the Committee of Privileges in the House of Lords. A tie vote resulted--Mohun voting in his own interests, Hamilton absent. When proxies were counted, Mohun prevailed in a vote of 40 to 36. And still they waited for the ruling from Chancery.

But it wasn't the courts that put an end to a dispute. It was, of course, a duel. Not a polite, mannerly affair between a pair of nobleman who deemed honour at risk. What occurred in Hyde Park on the early morning of 15th November was a brutal and decisive battle between bitter adversaries.

When the Duke of Hamilton, Lord Mohun, and Macartney [Mohun's second] came to the place agreed on them to fight, the Duke and Lord Mohun had no sooner drawn their swords than Macartney drew his, as Colonel Hamilton did the same . . . he [the Colonel] striking down Macartney's sword...closed with Macartney and took his sword from him, by which time Lord Mohun was down on the ground and His Grace upon him. The Colonel, the better to help the Duke up, flung both swords upon the ground . . . Macartney came with a sword in his hand, and gave a thrust into the duke's left breast . . . the Duke at the same time saying, I am wounded, and whilst the said Colonel Hamilton was helping him Macartney escaped.

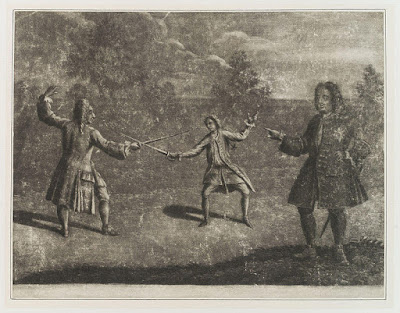

|

| A representation of the doubly fatal duel in Hyde Park |

The stab wound to the duke's chest was superfluous; one of Mohun's blows had severed the artery in his wrist. The two enemies lay dead, their blood seeping into the grass.

The Colonel stood trial, was convicted of manslaughter, branded with the cold iron, and went free. General Macartney fled England and tried to exonerate himself through pamphlets. While in Europe he gained an ally in the future George I and wished to follow the new King to England. He sought to have his outlawed status altered in order to belatedly stand trial for his role in the duel.

Two years later, when the case was finally heard, Hamilton said he couldn't swear that the accused had actually murdered the duke. Macartney likewise received a non-branding and went free--as the bad baron had done so many times in the course of his duelling career.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Margaret Porter is the award-winning and bestselling author of twelve period novels, whose other publication credits include nonfiction and poetry. One notorious incident in which Lord Mohun participated appears in A Pledge of Better Times, her highly acclaimed novel of 17th century courtiers Lady Diana de Vere and Charles Beauclerk, 1st Duke of St. Albans. Margaret studied British history in the UK and the US. As historian, her areas of speciality are social, theatrical, and garden history of the 17th and 18th centuries, royal courts, and portraiture. A former actress, she gave up the stage and screen to devote herself to fiction writing, travel, and her rose gardens.

Margaret Porter is the award-winning and bestselling author of twelve period novels, whose other publication credits include nonfiction and poetry. One notorious incident in which Lord Mohun participated appears in A Pledge of Better Times, her highly acclaimed novel of 17th century courtiers Lady Diana de Vere and Charles Beauclerk, 1st Duke of St. Albans. Margaret studied British history in the UK and the US. As historian, her areas of speciality are social, theatrical, and garden history of the 17th and 18th centuries, royal courts, and portraiture. A former actress, she gave up the stage and screen to devote herself to fiction writing, travel, and her rose gardens.

Connect with Margaret:

Website | Blog | Facebook | Twitter | Amazon

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.