by Maria Grace

During the long 18th century, the prevailing European attitude toward bathing was largely negative. Plunging oneself into water for the purpose of cleansing was inconvenient, expensive and according to many actually unhealthy. Consequently, what washing that was done focused on the hands and face, utilizing an ubiquitous wash stand found in nearly every bedroom.

During the long 18th century, the prevailing European attitude toward bathing was largely negative. Plunging oneself into water for the purpose of cleansing was inconvenient, expensive and according to many actually unhealthy. Consequently, what washing that was done focused on the hands and face, utilizing an ubiquitous wash stand found in nearly every bedroom.

These attitudes were so ingrained in British society that even as attitudes toward bathing began to change at the turn of the 19th century, English society was well known for their lack of cleanliness. Upper class English women were particularly known for their lack of attention to personal hygiene. The Handbook of Bathing (1841) notes

These attitudes were so ingrained in British society that even as attitudes toward bathing began to change at the turn of the 19th century, English society was well known for their lack of cleanliness. Upper class English women were particularly known for their lack of attention to personal hygiene. The Handbook of Bathing (1841) notes

While it would not be until the Victorian era that bathing became a moral imperative, attitudes definitely began to shift during the years of the Regency. During thus era, classical Greek and Roman influences impacted fashion and scholarship. The prevalence of bathing on both societies was not lost among scholars of the era. The Book of Health and Beauty (1837) notes:

While it would not be until the Victorian era that bathing became a moral imperative, attitudes definitely began to shift during the years of the Regency. During thus era, classical Greek and Roman influences impacted fashion and scholarship. The prevalence of bathing on both societies was not lost among scholars of the era. The Book of Health and Beauty (1837) notes:

Doctors and men of science began to suggest rather than be unhealthful, bathing was in fact, essential to health, particularly for the skin.

How did bathing act to improve health so greatly? Doctors noted,

This attitude represented a significant change from earlier days when bathing was thought to cause colds. ‘Modern doctors’ of the Regency began to recognize that

During the long 18th century, the prevailing European attitude toward bathing was largely negative. Plunging oneself into water for the purpose of cleansing was inconvenient, expensive and according to many actually unhealthy. Consequently, what washing that was done focused on the hands and face, utilizing an ubiquitous wash stand found in nearly every bedroom.

During the long 18th century, the prevailing European attitude toward bathing was largely negative. Plunging oneself into water for the purpose of cleansing was inconvenient, expensive and according to many actually unhealthy. Consequently, what washing that was done focused on the hands and face, utilizing an ubiquitous wash stand found in nearly every bedroom. These attitudes were so ingrained in British society that even as attitudes toward bathing began to change at the turn of the 19th century, English society was well known for their lack of cleanliness. Upper class English women were particularly known for their lack of attention to personal hygiene. The Handbook of Bathing (1841) notes

These attitudes were so ingrained in British society that even as attitudes toward bathing began to change at the turn of the 19th century, English society was well known for their lack of cleanliness. Upper class English women were particularly known for their lack of attention to personal hygiene. The Handbook of Bathing (1841) notes In sad and sober earnest, the English themselves are much less cleanly about their persons than either the French, the Italians, or even the Russians whom they place almost out of the pale of civilization (sic). The English are habitually well dressed; and every Englishman, above the operative classes, generally appears with a clean face, clean hands, and the finger-nails carefully cleaned. The other parts of his body … seldom, if ever, feel the comfort of ablution. The bodies of the generality of Englishmen are never washed, but are covered with epidermal incrustations of years' duration. Even those who seek recreation in swimming … become not a whit the cleaner for such immersion, because cold water cannot sufficiently act in so short a time upon the accumulation of coagulated perspiration and epidermal scales. Friction is seldom applied, or, if it be used, it consists only of a gentle wiping with a towel.

While it would not be until the Victorian era that bathing became a moral imperative, attitudes definitely began to shift during the years of the Regency. During thus era, classical Greek and Roman influences impacted fashion and scholarship. The prevalence of bathing on both societies was not lost among scholars of the era. The Book of Health and Beauty (1837) notes:

While it would not be until the Victorian era that bathing became a moral imperative, attitudes definitely began to shift during the years of the Regency. During thus era, classical Greek and Roman influences impacted fashion and scholarship. The prevalence of bathing on both societies was not lost among scholars of the era. The Book of Health and Beauty (1837) notes: The use of the bath was general among the Greeks and Romans; and to this salutary habit the Physician Baglivi ascribes the long and vigorous lives of the ancients. If we compare the manner of living among the Romans with that of our own at the present day, it will be seen how much nearer the former approached to nature, and how much more favourable it was to health. … everyone has tended to the bath; and no person could neglect this practice without incurring the charge of shameful negligence of health and decency. … Bathing may also be considered as an excellent specific for alleviating both mental and bodily afflictions, it is not merely a cleanser of the skin, enlivening and rendering it more fit for performing its offices; but it also refreshens the mind, and spreads over the whole system a sensation of ease, activity, and agreeableness.

Doctors and men of science began to suggest rather than be unhealthful, bathing was in fact, essential to health, particularly for the skin.

The condition of the skin is the truest indication of health. By neglecting to and healthy condition, which in almost every case depends upon bodily cleanliness, many loathsome diseases are engendered ... The skin is the most sensitive and excitable part of the human frame; for it is the indicator of sensation from without to every other part of the body. … In the cities and towns of France, cutaneous diseases arising from want of general bodily ablution, are much less common than with us (English), because the poorest of the operatives enjoy, from time to time, the luxury of warm bathing.

How did bathing act to improve health so greatly? Doctors noted,

free perspiration, sensible and insensible, is so necessary to the human physical condition, that without it, fever headache, and inflammation, ensue. Also, that the skin itself, by a disordered state of the exhalant vessels or their extremities, forming the pores or outlets, becomes unhealthy, and by being so, disturbs the action of the stomach and alimentary canal, whereby the functions of digestion are impeded, the frame debilitated, and the whole animal economy thrown into confusion. Now, if for want of bathing and friction, a crust of epidermal scales is allowed to form upon the skin, instead of being constantly removed, some of the perspiratory pores are closed, whilst a portion of the aqueous fluid perspired remains coagulated at their orifices under the crust, and … an extremely offensive fermentation soon takes place. … If one tenth of the persevering attention and labour bestowed to so much purpose in rubbing down and currying the skins of horses, were bestowed by the human race in keeping themselves in good condition, and a little attention were paid to diet and clothing,—colds, nervous diseases, and stomach complaints, would cease to form so large an item of the catalogue of human miseries.(Combe, 1836)

This attitude represented a significant change from earlier days when bathing was thought to cause colds. ‘Modern doctors’ of the Regency began to recognize that

scantiness of clothing, aided by the absence of body washing and skin-rubbing, bring "colds" and "consumption" to the females of [England … As it is, colds attend their footsteps, ever ready to place them within the deadly embrace of consumption, because they omit keeping their skin in a condition to resist the changes that daily occur in our atmosphere… Now, as they are neglected by the great majority of the British population, there is among that population a tendency to "catch cold," erroneously attributed to the climate ; whilst in countries possessing even a less benignant clime, but where the use of warm-bathing and friction is adopted by the inhabitants, this facility of catching cold does not exist.

(The Handbook of the Toilette, 1841)

Though science and scholarship might argue for bathing, changes in public opinion spread more rapidly as social leaders demonstrated new ways. Both Beau Brummell and the Prince Regent were known for their distinct bathing habits. Brummell bathed daily in hot water and exfoliated his body with a coarse-hair brush. He purchased expensive soap, brushes and razors from Renard's of St. James's, along with toothbrushes, nail brushes, combs and soap.

Public policy followed after these social changes as demonstrated by the 1814 Thames Bathing Bill. The act corrected the most injurious encroachment on the comfort of the lower classes set forth in the Thames Police act. The later deprived commoners the right to bathe in the Thames during daylight hours. It levied a fine on those who dared defy the order.

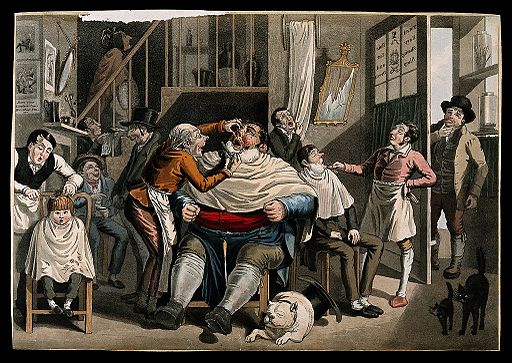

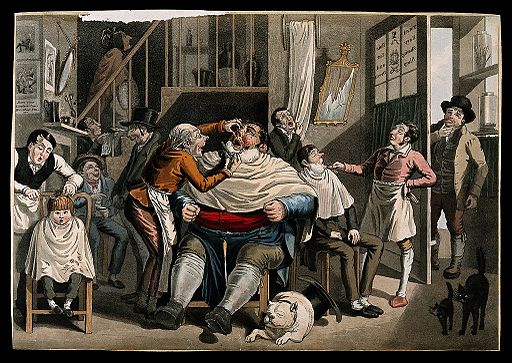

As bathing and cleanliness became increasingly important to both people of fashion and society at large, merchants capitalized upon the trend. Shaving became increasingly important, with many men shaving themselves during their regular ablutions, rather than visiting barbers. The fine razors made in Sheffield, England became greatly prized. Scented soaps and toilet waters also became popular, both for purchase and to be made at home.

As bathing and cleanliness became increasingly important to both people of fashion and society at large, merchants capitalized upon the trend. Shaving became increasingly important, with many men shaving themselves during their regular ablutions, rather than visiting barbers. The fine razors made in Sheffield, England became greatly prized. Scented soaps and toilet waters also became popular, both for purchase and to be made at home.

Moreover authors and other purveyors of advice offered a myriad of suggestions on how to bath (cold, warm, hot…) and with what preparations to bath. The next part of this article will examine recommendations on how to bath during Regency era.

Bibliography

A Lady of Distinction. Regency Etiquette: The Mirror of Graces (1811). Enl. ed. Mendocino, CA: R.L. Shep ;, 1997.

Buc'hoz, Pierre-Joseph. The Toilet of Flora Or, a Collection of the Most Simple and Approved Methods of Preparing Baths, Essences, Pomatums, Powders, Perfumes, Sweet-Scented Waters, and Opiates for Preserving and Whitening the Teeth, &c. &c. With Receipts for Cosmetics of Every Kind, That Can Smooth and Brighten the Skin, Give Force to Beauty, and Take off the Appearance of Old Age and Decay. For the Use of the Ladies. Improved from the French of M. Buchoz, M.D. London: Printed for J. Murray, Mo 12 Fleet-street and W. Nicoll, No. 51, in St. Paul's Church Yard, 1784.

Combe, Andrew M.D. The Principles of Physiology applied to the Preservation of Health, and to the Improvement of Mental and Physical Education. Fifth Edition. Edinburgh: Maclachlan and Stewart. London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co. 1836.

Corbould, H. The Art of Beauty, Or, The Best Methods of Improving and Preserving the Shape, Carriage, and Complexion ; Together with the Theory of Beauty. London: Printed for Knight and Lacey ... and Westley and Tyrrell, Dublin, 1825.

Currie, James (1805). "Medical Reports, on the Effects of Water, Cold and Warm, as a remedy in Fever and Other Diseases, Whether applied to the Surface of the Body, or used Internally". Including an Inquiry into the Circumstances that render Cold Drink, or the Cold Bath, Dangerous in Health, to which are added; Observations on the Nature of Fever; and on the effects of Opium, Alcohol, and Inanition. Vol.1 (4th, Corrected and Enlarged ed.). London: T. Cadell and W. Davies. p. ii. Retrieved 2 December 2009. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780-1850. Repr. ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

Gatrell, Vic. City of London: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-century London. New York: Walker &, 2006.

Kane, Kathryn. "Soap in the Regency — Bar or Barrel?" The Regency Redingote. April 23, 2010. Accessed June 5, 2015.

Kelly, Ian. Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style. New York: Free Press, 2006.

Murray, Venetia, and Venetia Murray. An Elegant Madness: High Society in Regency England. New York: Penguin Books, 2000.

Radcliffe, M. A Modern System of Domestic Cookery Or, The Housekeeper's Guide, Arranged on the Most Economical Plan for Private Families ... : A Complete Family Physician, and Instructions to Female Servants in Every Situation, Showing the Best Methods of Performing Their Various Duties ... to Which Are Added, as an Appendix, Some Valuable Instructions on the Management of the Kitchen and Fruit Gardens. Manchester: J. Gleave, 1823.

Snively, John H. A Treatise on the Manufacture of Perfumes and Kindred Toilet Articles. Nashville: C.W. Smith, 1877.

Stone, Lawrence. The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800. Abridged ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

The Art of Preserving the Hair on Philosophical Principles. By the Author of The Art of Improving the Voice. London: Printed for Septimus Prowett, Old Bond Street, 1825.

The Book Of Health & Beauty, Or The Toilette Of Rank And Fashion: Embracing the economy of the beard eye-brows gums nails breath eye-lashes hands skin complexion feet lips teeth eyes hair mouth tongue, 8::- 81c. with recipes, and directions for use, of safe and salutary cosmetics— perfumes—essences-simple waters—depilatories, etc. and a variety “ select recipes for the dressing room of both sexes. 2nd ed. London: Joseph Thomas, 1, Finch Lane, Cornhill, 1837.

The Book of Health; a Compendium of Domestic Medicine, Deduced from the Experience of the Most Eminent Modern Practitioners: Including the Mode of Treatment for Diseases in General; a Plan for the Management of Infants and Children; Rules for the Preserva. London: Vizetelly, Branston, 1828.

The Hand-book of Bathing. London: W.S. Orr, 1841.

The Hand-book of the Toilette. 2nd ed. London: W.s. Orr and, 1841.

The New London Toilet: Or, a Compleat Collection of the Most Simple and Useful Receipts for Preserving and Improving Beauty, Either by Outward Application or Internal Use. With Many Other Valuable Secrets in Elegant and Ornamental Arts. Containing near Four Hundred Receipts under the following General Heads. Perfumes Fine Waters Baths Cosmetics Conserves Confectionary Snuffs Pastes Wash Balls Scented Powders Pomatums Fine Syrups Jellys Preserved Fruits, &c. With Every Species of Cosmetic That May Be Useful in Improving Beauty, or Concealing the Ravages of Time and Sickness. To Which Is Added a Treatise on the Art of Managing, Improving, and Dressing the Hair on the Most Improved Principles of That Art. London: Printed for Richardson and Urquhart, under the Royal-Exchange, 1778.

The Toilette of Health, Beauty, and Fashion: Embracing the Economy of the Beard, Breath, Complexion, Ears, Eyes, Eye-brows, Eye Lashes, Feet, Forehead, Gums, Hair, Head, Hands, Lips, Mouth, Mustachios, Nails of the Toes, Nails of the Fingers, Nose, Skin, Teeth, Tongue, Etc., Etc., : Including the Comforts of Dress and the Decorations of the Neck ... with Directions for the Use of Most Safe and Salutary Cosmetics ... and a Variety of Selected Recipes for the Dressing Room of Both Sexes. Boston: Allen and Ticknor, 1833.

Walton, Geri. "18th and 19th Century: Baths for Medicinal Purposes." 18th and 19th Century: Baths for Medicinal Purposes. February 12, 2014. Accessed June 5, 2015. http://18thcand19thc.blogspot.com/2014/02/baths-for-medicinal-purposes.html

Walton, Geri. "18th and 19th Century: Health Remedies, Preventatives, and Cures in the 1700 and 1800s." 18th and 19th Century: Health Remedies, Preventatives, and Cures in the 1700 and 1800s. February 20, 2014. Accessed June 5, 2015. http://18thcand19thc.blogspot.com/2014/02/health-remedies-preventatives-and-cures.html

Wilcox, R. Turner. The Mode in Hats and Headdress: A Historical Survey with 198 Plates. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover, 2008.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Maria Grace is the author of Darcy's Decision, The Future Mrs. Darcy, All the Appearance of Goodness, and Twelfth Night at Longbourn and Remember the Past. Click here to find her books on Amazon. For more on her writing and other Random Bits of Fascination, visit her website. You can also like her on Facebook, follow on Twitter or email her.

Public policy followed after these social changes as demonstrated by the 1814 Thames Bathing Bill. The act corrected the most injurious encroachment on the comfort of the lower classes set forth in the Thames Police act. The later deprived commoners the right to bathe in the Thames during daylight hours. It levied a fine on those who dared defy the order.

As bathing and cleanliness became increasingly important to both people of fashion and society at large, merchants capitalized upon the trend. Shaving became increasingly important, with many men shaving themselves during their regular ablutions, rather than visiting barbers. The fine razors made in Sheffield, England became greatly prized. Scented soaps and toilet waters also became popular, both for purchase and to be made at home.

As bathing and cleanliness became increasingly important to both people of fashion and society at large, merchants capitalized upon the trend. Shaving became increasingly important, with many men shaving themselves during their regular ablutions, rather than visiting barbers. The fine razors made in Sheffield, England became greatly prized. Scented soaps and toilet waters also became popular, both for purchase and to be made at home.Moreover authors and other purveyors of advice offered a myriad of suggestions on how to bath (cold, warm, hot…) and with what preparations to bath. The next part of this article will examine recommendations on how to bath during Regency era.

Bibliography

A Lady of Distinction. Regency Etiquette: The Mirror of Graces (1811). Enl. ed. Mendocino, CA: R.L. Shep ;, 1997.

Buc'hoz, Pierre-Joseph. The Toilet of Flora Or, a Collection of the Most Simple and Approved Methods of Preparing Baths, Essences, Pomatums, Powders, Perfumes, Sweet-Scented Waters, and Opiates for Preserving and Whitening the Teeth, &c. &c. With Receipts for Cosmetics of Every Kind, That Can Smooth and Brighten the Skin, Give Force to Beauty, and Take off the Appearance of Old Age and Decay. For the Use of the Ladies. Improved from the French of M. Buchoz, M.D. London: Printed for J. Murray, Mo 12 Fleet-street and W. Nicoll, No. 51, in St. Paul's Church Yard, 1784.

Combe, Andrew M.D. The Principles of Physiology applied to the Preservation of Health, and to the Improvement of Mental and Physical Education. Fifth Edition. Edinburgh: Maclachlan and Stewart. London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co. 1836.

Corbould, H. The Art of Beauty, Or, The Best Methods of Improving and Preserving the Shape, Carriage, and Complexion ; Together with the Theory of Beauty. London: Printed for Knight and Lacey ... and Westley and Tyrrell, Dublin, 1825.

Currie, James (1805). "Medical Reports, on the Effects of Water, Cold and Warm, as a remedy in Fever and Other Diseases, Whether applied to the Surface of the Body, or used Internally". Including an Inquiry into the Circumstances that render Cold Drink, or the Cold Bath, Dangerous in Health, to which are added; Observations on the Nature of Fever; and on the effects of Opium, Alcohol, and Inanition. Vol.1 (4th, Corrected and Enlarged ed.). London: T. Cadell and W. Davies. p. ii. Retrieved 2 December 2009. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780-1850. Repr. ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

Gatrell, Vic. City of London: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-century London. New York: Walker &, 2006.

Kane, Kathryn. "Soap in the Regency — Bar or Barrel?" The Regency Redingote. April 23, 2010. Accessed June 5, 2015.

Kelly, Ian. Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style. New York: Free Press, 2006.

Murray, Venetia, and Venetia Murray. An Elegant Madness: High Society in Regency England. New York: Penguin Books, 2000.

Radcliffe, M. A Modern System of Domestic Cookery Or, The Housekeeper's Guide, Arranged on the Most Economical Plan for Private Families ... : A Complete Family Physician, and Instructions to Female Servants in Every Situation, Showing the Best Methods of Performing Their Various Duties ... to Which Are Added, as an Appendix, Some Valuable Instructions on the Management of the Kitchen and Fruit Gardens. Manchester: J. Gleave, 1823.

Snively, John H. A Treatise on the Manufacture of Perfumes and Kindred Toilet Articles. Nashville: C.W. Smith, 1877.

Stone, Lawrence. The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800. Abridged ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

The Art of Preserving the Hair on Philosophical Principles. By the Author of The Art of Improving the Voice. London: Printed for Septimus Prowett, Old Bond Street, 1825.

The Book Of Health & Beauty, Or The Toilette Of Rank And Fashion: Embracing the economy of the beard eye-brows gums nails breath eye-lashes hands skin complexion feet lips teeth eyes hair mouth tongue, 8::- 81c. with recipes, and directions for use, of safe and salutary cosmetics— perfumes—essences-simple waters—depilatories, etc. and a variety “ select recipes for the dressing room of both sexes. 2nd ed. London: Joseph Thomas, 1, Finch Lane, Cornhill, 1837.

The Book of Health; a Compendium of Domestic Medicine, Deduced from the Experience of the Most Eminent Modern Practitioners: Including the Mode of Treatment for Diseases in General; a Plan for the Management of Infants and Children; Rules for the Preserva. London: Vizetelly, Branston, 1828.

The Hand-book of Bathing. London: W.S. Orr, 1841.

The Hand-book of the Toilette. 2nd ed. London: W.s. Orr and, 1841.

The New London Toilet: Or, a Compleat Collection of the Most Simple and Useful Receipts for Preserving and Improving Beauty, Either by Outward Application or Internal Use. With Many Other Valuable Secrets in Elegant and Ornamental Arts. Containing near Four Hundred Receipts under the following General Heads. Perfumes Fine Waters Baths Cosmetics Conserves Confectionary Snuffs Pastes Wash Balls Scented Powders Pomatums Fine Syrups Jellys Preserved Fruits, &c. With Every Species of Cosmetic That May Be Useful in Improving Beauty, or Concealing the Ravages of Time and Sickness. To Which Is Added a Treatise on the Art of Managing, Improving, and Dressing the Hair on the Most Improved Principles of That Art. London: Printed for Richardson and Urquhart, under the Royal-Exchange, 1778.

The Toilette of Health, Beauty, and Fashion: Embracing the Economy of the Beard, Breath, Complexion, Ears, Eyes, Eye-brows, Eye Lashes, Feet, Forehead, Gums, Hair, Head, Hands, Lips, Mouth, Mustachios, Nails of the Toes, Nails of the Fingers, Nose, Skin, Teeth, Tongue, Etc., Etc., : Including the Comforts of Dress and the Decorations of the Neck ... with Directions for the Use of Most Safe and Salutary Cosmetics ... and a Variety of Selected Recipes for the Dressing Room of Both Sexes. Boston: Allen and Ticknor, 1833.

Walton, Geri. "18th and 19th Century: Baths for Medicinal Purposes." 18th and 19th Century: Baths for Medicinal Purposes. February 12, 2014. Accessed June 5, 2015. http://18thcand19thc.blogspot.com/2014/02/baths-for-medicinal-purposes.html

Walton, Geri. "18th and 19th Century: Health Remedies, Preventatives, and Cures in the 1700 and 1800s." 18th and 19th Century: Health Remedies, Preventatives, and Cures in the 1700 and 1800s. February 20, 2014. Accessed June 5, 2015. http://18thcand19thc.blogspot.com/2014/02/health-remedies-preventatives-and-cures.html

Wilcox, R. Turner. The Mode in Hats and Headdress: A Historical Survey with 198 Plates. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover, 2008.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Maria Grace is the author of Darcy's Decision, The Future Mrs. Darcy, All the Appearance of Goodness, and Twelfth Night at Longbourn and Remember the Past. Click here to find her books on Amazon. For more on her writing and other Random Bits of Fascination, visit her website. You can also like her on Facebook, follow on Twitter or email her.

This was a fascinating article, and well-written. I can't imagine how they put up with the body odors that must have accompanied lack of bathing in those early days. And it's amazing to think that upper class men and women would dress up in fine clothes, but be unbathed.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Elizabeth. I think we are much more sensitized to body odors today. In an era where everyone smelled 'natural' I think it was much less a noticeable thing. Still, I don't think I'd want to go back to that now! LOL

DeleteI once read a great article about the advent of showers in the U.S. in the early days of the nation. People were either scandalized or titillated by the idea of "being wet all over," but getting naked was unseemly, so they often wore clothing in the shower to keep their modestly intact.

ReplyDeleteIt was similar in Europe as well. People often wore a shift while they bathed for the same reason. It took a while for 'getting wet all over' and being unclothed in the process to catch on. Thanks, Peg!

DeleteFascinating article. Thank you so much for sharing.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Gill!

DeleteVery interesting and educational. Thank you for sharing!

ReplyDeleteThank you Farida!

DeleteNow I am even more convinced I never want to travel back in time! :-) "an extremely offensive fermentation soon takes place. …" enough said! But seriously, this post is nicely done. Thank you for sharing it.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Tracy. I found those descriptions rather evocative, and not in the most pleasant way!

DeleteRemember that development is not lineal! Bathing was a integral and important feature of medieval society. By the fifteenth century, the magnates even had hot and cold running water in their castles (e.g. the Percys at Warkworth, the Prince of Wales and Aquitaine at Kennington)! The poor had bath houses (aka stews, remember that earlier entry?) There are numerous medieval illustrations of people bathing, and in chivalric romance it was conventional for a knight or lord, arriving as a guest at a strange castle or coming home after a journey, to be given a bath first.

ReplyDeleteIt was not until the 16th century and the Reformation that bathing came into ill-repute. Increasing crowding in cities led to increasingly unsanitary conditions and contaminated water that carried disease. Bathing in public places became an increasing health hazard. Equally important, increasingly puritanical religious leaders found the mixing of sexes at public baths and the tradition of women helping men at the baths even in the upper classes -- "immoral." So bathing -- and going naked -- became "evil," "sinful" and by inference "unhealthy" -- since if it was unhealthy for the soul it must also be unhealthy for the body.

Thanks for the reminder of how we came to the conclusion that bathing was unhealthy in the first place.

DeleteYour point about development not be linear is well taken. Since my focus was the Georgian era, I had not thought to trace the history of the attitude back prior to that era, especially since other posts on the site cover that aspect so well.

I think Scandinavia had different standards. I've been doing research in the 11th century for a medieval and discovered that, even then, the Danes bathed more frequently than the Normans or the English.

ReplyDeleteI think you're right about Scandinavia having different standards.

DeleteDuring the Georgian era, the English had a particular reputation for lack of cleanliness.

Great article!! I would like to ask about the 1995 adaptation of P&P when Darcy takes a bath. Was that really likely? I hate to think that Mr. Darcy did not smell good. LOL. Unfortunately I lived in England for a year and the professors at the university (not all of them but several) did display that dried crust of dead skin and old sweat on their heads (hair and ears mostly). It was disgusting!

ReplyDeleteOoo, Rita that image of your professors gave me the shudders. Yes, he might have taken a bath that way, but tubs like that were found in only a few of the wealthiest homes. Hip baths were far more common.

Delete