This article is about the lives of three remarkable women; Grace Ashley Smith, Mabel Stobart and Flora Sands:

Ashley Smith joined the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry in the early years of the 20th century and rose to take command at a time when the organisation was in danger of collapsing. The FANY had been founded in 1907 with the idea that it would provide a corps of mounted nurses who could gallop onto the battle field to render First Aid to the wounded but there had been disputes and the membership was dropping off. She 'pulled it up by its boot straps' and instituted a training regime that made it so efficient that it was commended by Sir Arthur Sloggett, the Chief Commissioner of the Red Cross.

There was rigorous training in all aspects of First Aid, and the skills needed to survive in conditions near the front line. For the first time women went under canvas and learned camp cookery, signalling and related subjects. However, when she offered the corps' services at the beginning of World War I they were turned down by the War Office, who wanted nothing to do with women at the front line. Nothing daunted, Smith arranged with the Belgians to set up a hospital in Calais, where the FANY girls did wonderful service collecting and caring for wounded men. They were the first women to drive ambulances under fire and many of them received awards for gallantry.

Mabel Stobart was born in 1862. She married and lived in Africa and British Columbia but after the death of her husband she returned to London in 1907. She found the city, and indeed the whole country, gripped by the fear of invasion by Germany. In that climate a play, 'An Englishman's Home', was staged which pointed out how helpless the average middle-class household would be in that event, and in particular how ill-equipped the women would be to do anything to help their menfolk.

This inspired Stobart to take steps to rectify the situation. She was a supporter of women's suffrage but did not approve of the suffragettes. In her autobiography, Miracles and Adventures, she wrote:

'My feeling was that if women desired to have a share in the government of the country, and this seemed a legitimate ambition, they ought to be capable of taking a share in the defence of their country. I thought that in the present agitation women were putting the cart before the horse, and I made up my mind to try to provide proof of women's national worthiness, in the belief that political enfranchisement would be the natural corollary ... I certainly did not want them to fight, to take life. Nature asks us to create life, a responsibility we have accepted much too lightly ... What was there we could do, or should be allowed to do, in case of foreign invasion?'

To begin with she joined the FANY, but around 1912 a dispute arose, the origins of which are somewhat mysterious, and several members broke away, Stobart among them. She then founded her own organisation, The Women's Sick and Wounded Convoy. Its aims were very much the same as those of the FANY, i.e. to render First Aid to those wounded in battle and to transport them to the nearest Field Hospital. When the First Balkan War broke out between Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece on the one hand and the Ottoman Empire on the other Stobart saw this as a perfect opportunity to prove that her ideas could work in practice. She took a group of women nurses and doctors to Sophia, the capital of Bulgaria, and persuaded the Tsar and his generals to allow them to set up a hospital in Lozengrad, the nearest point to the front line which they were allowed to reach. The journey took six days, in ox carts over roads deep in mud, and when they arrived they had first to find a suitable building and then set it up as a hospital from scratch. That they achieved this was a remarkable tribute to their tenacity and determination. It was the first field hospital to be staffed entirely by women.

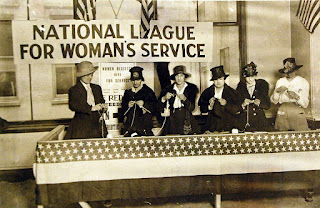

When the First World War started in 1914 Stobart joined with Lady Muir McKenzie to found the Women's National Service League. She went to Belgium to set up a hospital but was captured by the Germans and almost shot as a spy. However, she escaped and once the hospital was established she left for the Balkans again, this time for Serbia where she had been invited to set up a hospital outside Kragujevac. From there she led a mobile field hospital up to the front line but, when the Bulgarians - who were now fighting on the side of the Central Powers - attacked, the Serbian army was forced into a desperate retreat through the mountains of Albania in the dead of winter. It is one of the epic stories of the war. The conditions were terrible; the roads were merely tracks, often too narrow even for a cart to pass and the snow was up to the horses' knees. There were no supplies and the local people were hostile. Thousands died. Somehow Stobart brought her unit through to safety on the Adriatic coast, often spending eighteen hours a day on horseback - an amazing feat for a woman of fifty-three. They were taken off by ship and reached Italy, from where they were able to return to England. If Stobart expected a hero's welcome and recognition of her aim to prove women as capable as men of enduring hardship in the service of their country, she was disappointed.

Meanwhile, as mentioned above, the FANYs were doing sterling work in France.

In her book, A Woman Sergeant in the Serbian Army, Flora Sandes relates how she, too, went to Serbia as a nurse. She does not say under whose auspices, but FANY records show her as one of those who split from the organisation at the same time as Stobart so it seems likely that she went with The Women's Sick and Wounded Convoy. In the course of the retreat she was separated from her unit and taken into the protection of a company of Serbian soldiers.

She witnessed their conduct in several rear-guard actions and finally demanded a gun of her own so that she could play her part. She, too, was involved in the epic retreat through Albania. On reaching Durazzo (Durres) on the Adriatic coast many of the remnants of the Serbian army were taken by ship to Corfu and instead of going home Flora went with them. There they found that no facilities had been set up to receive them. There was no firewood and no food supplies. Single-handedly, Flora made her way to Corfu Town and confronted the British and French military authorities, who had taken over the island for the duration, forcing them to acknowledge the problem and take the necessary measures.

By this time she had been accepted as a regular member of the Serbian Army and at a ceremony a few months later she was given the rank of sergeant - the first woman to be officially recognised as a fighting soldier. After some months, the Serbs were re-equipped and sent to Salonika (modern day Thessaloniki) where a small force of British, French and Greek soldiers was prevented from advancing into Macedonia by superior numbers of Bulgarian troops. Eventually they succeeded in breaking out and the Serbs fought a bitter campaign, regaining their lost homeland mountain peak by mountain peak, until at last they re-entered Belgrade. Flora fought with them, in spite of being wounded and enduring the death of the soldier with whom she had fallen in love and almost dying from Spanish 'flu, which killed so many all over Europe. The collapse of German resistance in Serbia was the event which triggered the end of the war and brought about the Armistice.

[all photographs in the Public Domain, via Wikipedia. This is an archive Editor's Choice post, first published on EHFA on Nov 26, 2018]

~~~~~~~~~~

Hilary Green who also writes as Holly Green, is the author of fifteen historical novels, ranging from Bronze Age Greece to the Second World War. She has a B.Ed degree (First Class) and an MA in Writing. This post details the inspiration for three novels originally entitled Daughters of War; Passions of War and Harvest of War but recently republished by Penguin as Frontline Nurses, Frontline Nurses on Duty and Secrets of the Frontline Nurses. Book 1 is available as a paperback, books 2 and 3 are available on line and will be in print in due course.

Connect with Hilary: www.hilarygreen.co.uk

_(37634620435)_cropped.jpg/600px-Castle_Howard%2C_Yorkshire%2C_UK%2C_17112017%2C_JCW1967_(12)_(37634620435)_cropped.jpg)