By Catherine Curzon

It seems, whenever an election rears its head, that discussion of how well Parliament represents the electorate is not far behind. In our twenty-first century world, it is taken as a given that voters in the United Kingdom can go to polls and choose their favoured candidate. Of course, there remains the perennial problem of low voter turnout but one wonders, had they been present during 18th century struggles to secure the vote for working men, whether these unenthusiastic members of the electorate might well think twice before electing not to exercise their democratic right.

In 1792, the Houses of Parliament were a very different place, and the right to vote was not one afforded to women, nor even to all men. For too long seen as the preserve of an elite monied and educated few, English politics seemed due for a change and it the vanguard of this new political movement were attorney John Frost and radical shoemaker Thomas Hardy.

Frost and Hardy envisioned a world where men of all classes could have their say; where enlightened thought and debate could be enjoyed without limit and where no man, regardless of his trade or birthright, was afraid to make his voice heard.

Frost and Hardy founded the London Corresponding Society on 25th January 1792 and set their subscription rates low, encouraging those with little money to participate. Their focus of winning representation and the vote for all men did nothing to endear the pair to the political and ecclesiastical establishment, but the pair were not to be silenced. The Society's most important aim was to force reform on the British parliament, with a central belief that the working classes and the poor should finally be given a voice. The members of the group loudly and vociferously opposed the government on a number of points and before long, opposition to their aims found itself on the backfoot, as affiliate groups sprang up throughout the land.

The Society welcomed these like-minded groups until, within 18 months, 6000 people had signed a petition in support of the aims of the LCS. This could not be allowed to go unchecked, of course, and the law soon came calling on Frost and Hardy.

During a convention of group leaders in Edinburgh in October 1793, the a number of attendees were arrested and placed on trial for treason. Whilst some were transported as a result, Frost was only imprisoned for six months and the intervention did little to deter the members of the Society, who held up their persecuted leaders as martyrs to a fine cause.

The following year yet more members of the Society were arrested, yet this time none of the charges of treason stuck. By now the Society that had started in a small pub was well known throughout England. Thousands of supporters attended public meetings and members even stoned the carriage of George II at the opening of Parliament.With Parliament and crown looking over the sea to the events of the French Revolution, such aggressive mobs were a step too far; stoned carriages carried echoes of the fall of the Bourbon monarchy and the government abandoned its programme of ineffective arrests and instead invoked the power of legislation.

The result was the Treasonable Practices Act and the Seditious Meetings Act of 1795. Although this did not outright criminalise the Society, it placed considerable restrictions on its actions. If the law was intended to put a stop to the gathering momentum of the Society, it succeeded admirably; more arrests sent a clear warning that the Act would be rigorously enforced and finally, as membership dwindled and infighting broke out, the Society began to fracture.

By 1798 small groups were forming away from the main Society and, though it struggled on for some time, the successful passage of the Corresponding Societies Act in 1799 proved the last nail in the coffin. The Act effectively outlawed any further meeting of the LCS and the Society and its affiliated groups faded into history, though their ideals and aims lived on in those who had been members.

References

The London Corresponding Society 1792-99. Michael T. Davis (ed.). London: Pickering & Chatto, 2002.

Selections From The Papers Of The London Corresponding Society. Mary Thale (ed.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Morning Post (London, England), Friday, April 26, 1793.

World (London, England), Friday, April 6, 1792

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It seems, whenever an election rears its head, that discussion of how well Parliament represents the electorate is not far behind. In our twenty-first century world, it is taken as a given that voters in the United Kingdom can go to polls and choose their favoured candidate. Of course, there remains the perennial problem of low voter turnout but one wonders, had they been present during 18th century struggles to secure the vote for working men, whether these unenthusiastic members of the electorate might well think twice before electing not to exercise their democratic right.

|

| LCS handbill, 1793 |

Frost and Hardy envisioned a world where men of all classes could have their say; where enlightened thought and debate could be enjoyed without limit and where no man, regardless of his trade or birthright, was afraid to make his voice heard.

Frost and Hardy founded the London Corresponding Society on 25th January 1792 and set their subscription rates low, encouraging those with little money to participate. Their focus of winning representation and the vote for all men did nothing to endear the pair to the political and ecclesiastical establishment, but the pair were not to be silenced. The Society's most important aim was to force reform on the British parliament, with a central belief that the working classes and the poor should finally be given a voice. The members of the group loudly and vociferously opposed the government on a number of points and before long, opposition to their aims found itself on the backfoot, as affiliate groups sprang up throughout the land.

The Society welcomed these like-minded groups until, within 18 months, 6000 people had signed a petition in support of the aims of the LCS. This could not be allowed to go unchecked, of course, and the law soon came calling on Frost and Hardy.

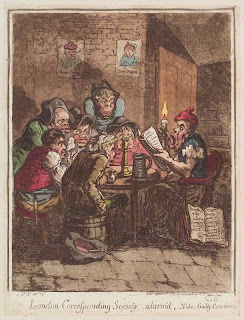

|

| London Corresponding Society, alarm's' by James Gillray, 1798 |

The following year yet more members of the Society were arrested, yet this time none of the charges of treason stuck. By now the Society that had started in a small pub was well known throughout England. Thousands of supporters attended public meetings and members even stoned the carriage of George II at the opening of Parliament.With Parliament and crown looking over the sea to the events of the French Revolution, such aggressive mobs were a step too far; stoned carriages carried echoes of the fall of the Bourbon monarchy and the government abandoned its programme of ineffective arrests and instead invoked the power of legislation.

The result was the Treasonable Practices Act and the Seditious Meetings Act of 1795. Although this did not outright criminalise the Society, it placed considerable restrictions on its actions. If the law was intended to put a stop to the gathering momentum of the Society, it succeeded admirably; more arrests sent a clear warning that the Act would be rigorously enforced and finally, as membership dwindled and infighting broke out, the Society began to fracture.

|

| Corresponding Society Meeting by James Gillray, 1795 |

By 1798 small groups were forming away from the main Society and, though it struggled on for some time, the successful passage of the Corresponding Societies Act in 1799 proved the last nail in the coffin. The Act effectively outlawed any further meeting of the LCS and the Society and its affiliated groups faded into history, though their ideals and aims lived on in those who had been members.

References

The London Corresponding Society 1792-99. Michael T. Davis (ed.). London: Pickering & Chatto, 2002.

Selections From The Papers Of The London Corresponding Society. Mary Thale (ed.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Morning Post (London, England), Friday, April 26, 1793.

World (London, England), Friday, April 6, 1792

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Glorious Georgian ginbag, gossip and gadabout Catherine Curzon, aka Madame Gilflurt, is the author of A Covent Garden Gilflurt’s Guide to Life. When not setting quill to paper, she can usually be found gadding about the tea shops and gaming rooms of the capital or hosting intimate gatherings at her tottering abode. In addition to her blog and Facebook, Madame G is also quite the charmer on Twitter. Her first book, Life in the Georgian Court, is available now, and she is also working on An Evening with Jane Austen, starring Adrian Lukis and Caroline Langrishe.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.