Last month I introduced the main auxiliary forces on which the British government relied

between 1793 and 1815 to defend the nation against a French invasion.

By 1804 up to 90,000 militia (raised by ballot) and over 400,000

volunteers (organised by statute but raised locally) were available

to act alongside the regular forces in case of attack.

Today I will focus on

one corps of Volunteers in particular: the Cinque Ports Volunteers,

formed in 1794, briefly disbanded 1802-3, and reformed 1803-9.

|

| French Map of the Cinque Ports (Wikimedia Commons) |

The Cinque Ports

Volunteers would have been on the front lines of defence had the French ever decided

to cross the Channel. The Cinque Ports was an ancient trade

confederation consisting of Hastings, New Romney, Hythe, Dover, and

Sandwich, along with the Antient Towns of Winchelsea and Rye, and the

Confederation Towns of Faversham, Folkestone, Lydd, Margate,

Ramsgate, and Tenterden. All were in Kent and East Sussex, many

within sight of French soil. Their importance in terms of national

defence is best demonstrated by the number of castles built over the

centuries, such as Dover, Deal, Walmer, and Sandown.

The Cinque Ports

Volunteers, 1794 – 1802

The Cinque Ports responded to the government circular of 1794 calling

for volunteers by forming Yeomanry (cavalry) and Fencible (infantry,

short for “Defencibles”) regiments, along with artillery units at

Deal and Sandown.

The

Cinque Ports Fencible Cavalry was commanded by Robert

Bankes-Jenkinson, a future prime minister (as Lord Liverpool). Nearly

500 men, including officers and NCOs, enlisted. The Cinque Ports

Fencibles were sent to Scotland in 1796, where they assisted in the

funeral of the poet Robert Burns.

Despite

being raised in response to an invasion threat, however, the

Fencibles were rarely used for purposes other than peace-keeping and

quelling civil unrest, as well as suppressing smuggling. They were

disbanded in 1802 on the signing of the Peace of Amiens, which

ushered in a truce between Britain and France.

The Cinque Ports

Volunteers, 1803 – 1809

In

May 1803, however, war broke out again with France. Napoleon

immediately made it clear he meant to attempt an invasion of Britain,

and positioned 150,000 men along the Channel coast for the purpose.

Henry Addington's government turned again to volunteers, and the

Cinque Ports once more responded enthusiastically -- this time with the personal involvement of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, former prime minister William Pitt the Younger.

|

| Walmer Castle (Wikimedia Commons) |

Pitt wrote in his capacity as Lord Warden to Lord

Hobart, the Secretary of State for War, on 27 July 1803:

I have the honour of transmitting enclosed a Memorandum of the proposal which I laid before your Lordship this morning for raising a Regiment of Volunteers within the Cinque Ports, to serve in case of invasion in any part of England, and to consist of three Battalions: and I have to request that your Lordship will submit the same to His Majesty's consideration.[1]

The

proposal was accepted, and three thousand men were raised between

July and November 1803. The officers were all local gentry and

aristocracy, but the rank and file were mostly skilled labourers and

artisans who could afford to leave their businesses for long

stretches. The three battalions were headed by Pitt's step-nephew,

Philip Stanhope, Lord Mahon; Robert Smith, Lord Carrington, Warden of

Deal Castle and Pitt's personal friend; and Thomas David Lamb, a

local dignitary from Rye.

The Volunteers were

required by statute to drill for at least two days a week, or 24 days' service

in three months. If there appeared to be a threat of invasion the men were called out on “Permanent Duty” and required to serve on

the same basis as regular troops, under martial law, until the threat

was over (they would, of course, be paid a shilling a day in

compensation for lost earnings – although in the case of the Cinque

Ports Volunteers, Pitt estimated the average man did not earn less

than 2s6d a day ordinarily).[2] In return the Volunteers received uniforms and weaponry from

the government, along with a very important benefit: exemption from

the militia ballot.

In

the 1790s the local gentlemen in charge of raising the volunteers had

been allowed to choose their uniforms, but in 1803 the government

wanted more control over the way the volunteers were raised and

deployed. They insisted that all volunteer infantry regiments should

be clothed in red, like the infantry.[3] The

Cinque Ports Volunteers, therefore, wore red uniforms faced in pale

yellow and blue pantaloons (white for ceremonial occasions), although

none of the Cinque Ports battalions had yet received their uniforms

before they were called out for the first time on Permanent Duty from

21 November to 14 December 1803.[4]

Military

men seemed generally impressed with the quality of the Cinque Ports

Volunteers, although some of what they said may of course have been

intended to flatter Pitt. Not everyone in the army, however, was delighted at the

prospect of working with "amateur" soldiers. Pitt allegedly

told General John Moore, who commanded the local regular encampment

at Shorncliffe, “On the very first alarm of the enemy's coming, I

shall march to aid you with my Cinque Ports Volunteers. You have not

yet told me where you will place us.”

Moore replied: “Do you see that

hill? You and yours shall be drawn up on it, where you will make a

most formidable appearance to the enemy, while I with my soldiers

shall fight on the beach.”[6]

The

Kentish Gazette

also seemed underwhelmed by the Volunteers' ability to act as a

military body. Remarking on the celebration of the King's official

birthday at Deal in June 1804, the newspaper reported in some

astonishment: “The Volunteers … fired three remarkably good

volleys”.[7]

| |

| William Pitt as Colonel of the Cinque Ports Volunteers |

Pitt's personal Volunteering zeal was well known. Some found it

amusing, but there was an element of respect even in the satire:

“Come

the Consul whenever he will,

And

he means it when Neptune is calmer,

Pitt

will send him a damn'd bitter pill

From

his fortress the castle of Walmer.”[8]

As

for Pitt himself, he was confident. A toast attributed to him at a

Volunteer dinner in 1803 went: “To a speedy meeting with the enemy

on our own

shores!”[9] At public

meetings with Cinque Ports dignitaries Pitt expressed his

expectations that the men of the Cinque Ports would rise to

Napoleon's challenge:

As the Cinque Ports had the honor to form the advanced guard of the nation, their exertions ought, and he trusted would be, such as to enable them fully to resist any attempt the enemy might make at landing … The county ought not to content itself with the limitation of volunteers directed by government, but … should shew itself worthy of the eminent character it retained in history, and by a suitable exertion, at least double its proportion … The situation of this country was widely different from the inland counties, and … one man near the coast was worth ten at a distance.[10]

Pitt's

example in leading his own men in the field – in the words of Lady

Hester Stanhope, his niece, he “absolutely goes through the fatigue

of a drill-sergeant … [and is] determined to remain acting Colonel

when his regiment is called into the field” – had its effect on

his men.[11] The Cinque Ports Volunteers were lucky to have such an

involved and colonel, and they repaid his enthusiasm. When Pitt

reviewed the Volunteers at Sandwich in November 1803 to tell them

they were being called out on Permanent Duty, they reacted cheerfully to the news:

The battalion being formed into a circle, the First Speaker in the world then addressed them in one of the most eloquent and impressive speeches that could be delivered … and though the wind was very high, his audience large, and very considerably extended, his stentorian voice carried his words home to every animated breast; and no sooner was his harangue completed, than the Margate companies set the example, which was immediately followed by the whole line, of declaring their unanimous approbation of the proposal, by giving their Colone nine of the most hearty cheers that ever proceeded from the lips of the Men of Kent.[12]

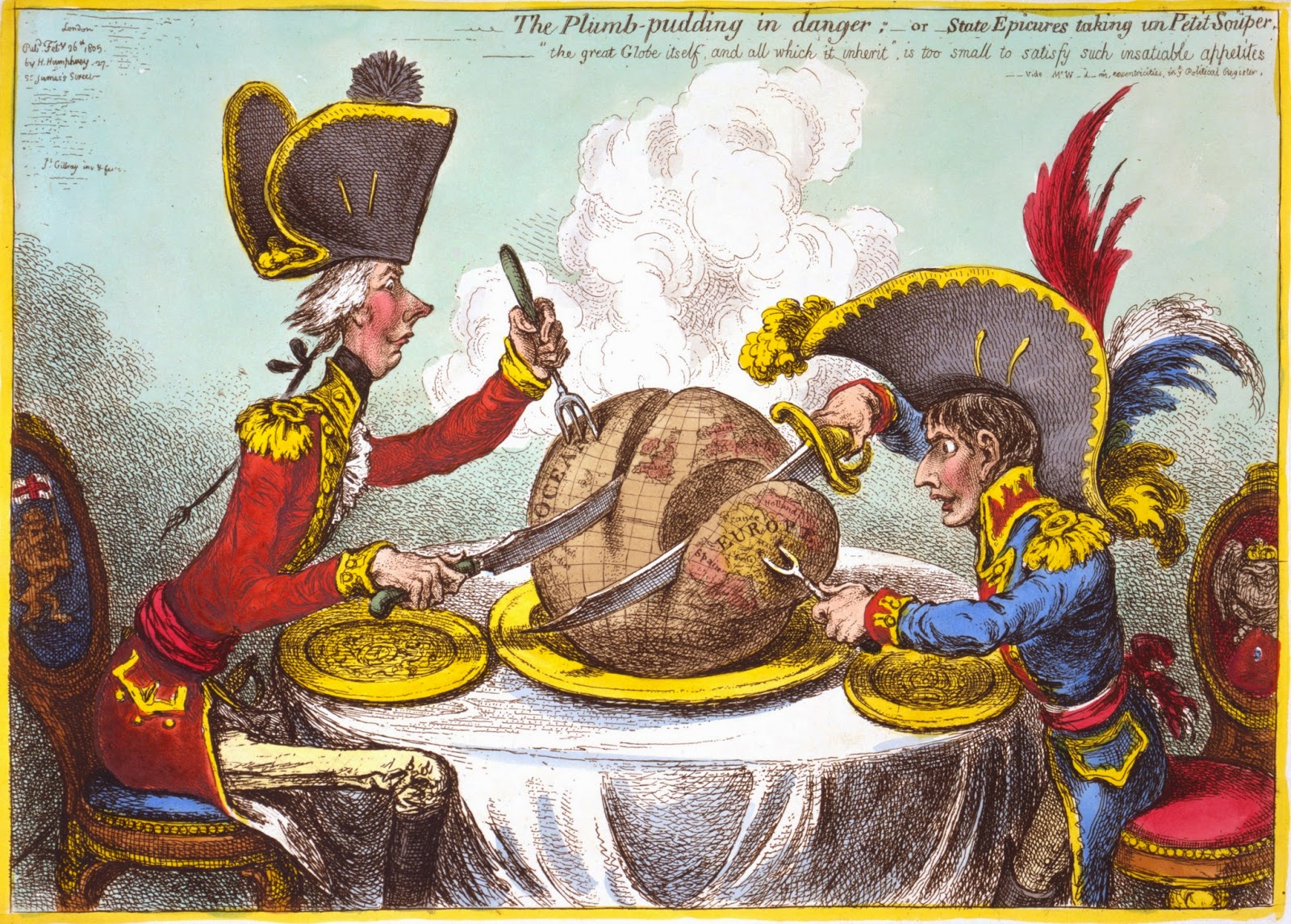

|

| Gillray's famous caricature of Pitt and Napoleon (1805). Pitt is wearing his CPV uniform |

The

end of the Cinque Ports Volunteers

Pitt died in January 1806. The

first two battalions of the Cinque Ports Volunteers attended his

funeral at Westminster Abbey, marching in the procession with black

bands around their arm. They had lost their Colonel, but they were

about to lose much more than that.

Pitt's

government was succeeded by Lord Grenville's “Ministry of All the

Talents”, which appointed William Windham – a long-standing enemy

of the Volunteers – as Secretary of State for War. Windham had a

low opinion of the Volunteers' ability to withstand an enemy

invasion: he much preferred the idea of relying on a strong regular

force, with a large auxiliary force, raised by ballot, to supplement

it. Windham's 1806 Training Act effectively killed the volunteer

movement by removing all government financial support and reducing

the hours spent training a year from 85 to 26.

Forced

to rely on their own devices, the Cinque Ports Volunteers could not

survive. The regiment issued a protest to the Secretary of State:

“Resolved, that it appears to us that the plan of Establishment

recently proposed to us by the Honourable Secretary … will

be attended with … serious difficulties, with considerable

individual expence, and must in a short time, render the Battalion

inefficient”.[13]

“I

have used my utmost endeavours to enduce as large a proportion of

[the men] to remain embodied as possible,” Lord Hawkesbury wrote to

the Secretary of State in September 1806. “... I think it right to

inform you that though some of the officers who belonged to the First

Battalion have tender'd their Resignations … I hope I shall be able

to preserve within the Town of Dover Four Companies of Eighty Men

Each which together with the Two Companies at Walmer, and four at

Faversham will form a respectable Force. I am in hopes likewise that

a greater Proportion of the Second Battalion will be dispos'd to

continue their services.” The Third Battalion issued its last pay

on 24 June 1806 and disbanded, although an Independent Company

continued in Rye till 1809.[14]

Despite

Hawkesbury's best efforts, attendance was already lapsing. “It

[has] been observed for many Months past that the Attendance of the

Corps instead of supporting its acquired Credit has most materially

disgraxced it & if persevered in will render it altogether

ineffectual,” was entered into the Battalion Order Book in

September 1806.[15] Pitt's death

and Windham's policies together spelled the end of the Cinque Ports

Volunteers.

The

regiment limped on a little longer, but by 1808 most of the remaining

men enlisted into the Local Militia, a force created by Lord

Castlereagh, Windham's successor as Secretary of State for War. It

was a sad end for Pitt's own Volunteers, but sadly not untypical. In

any case the immediate threat was past, and when a French invasion

again became an issue – in the 1850s and 1860s – the Cinque Ports

would again rise to the challenge.

______________

References

[1] National Archives Home Office Papers HO 50/63

[2] Pitt to Lord Hobart, 8 November 1803, National Archives Home Office Papers HO

50/63

[3] Lt. Col. Metzmen to William

Windham, 5 November 1803, British Library Add MSS 37882 ff 4-5

[4] Kentish

Chronicle,

28 October 1803; Kentish

Gazette

24 January 1804

[5] Kentish

Gazette

10 July 1804

[6] Richard Cannon, Historical

record of the Fourth, or King's Own Regiment of Foot

(London, 1839), p. 86

[7] Kentish

Gazette,

4 June 1804

[8] Peter Pindar [John Wolcot],

“Invitation to Bonaparte”, The

works of Peter Pindar

(London, 1835), p. 433

[9] Arthur Bryant, The

Years of Victory,

p. 67

[10] Kentish

Chronicle,

2 September 1803

[11] Lord Stanhope, Notes

and Extracts of letters referring to Mr Pitt and Walmer Castle

(London,

1866), p. 9

[12] Kentish

Chronicle,

17 November 1803

[13] National Archives Home Office Papers HO 50/151

[14] Lord Hawkesbury to ?, 9 September 1806,

National Archives Home Office Papers HO 50/151

[15] British Library Add MSS 38359 ff 79-80

______________

About the Author

Jacqui Reiter has a Phd in 18th century political history. She believes she is the world expert on the life of the 2nd Earl of Chatham, and is writing a novel about his relationship with his brother Pitt the Younger. When she finds time she blogs about her historical discoveries at http://alwayswantedtobeareiter.wordpress.com/.

Jacqui Reiter has a Phd in 18th century political history. She believes she is the world expert on the life of the 2nd Earl of Chatham, and is writing a novel about his relationship with his brother Pitt the Younger. When she finds time she blogs about her historical discoveries at http://alwayswantedtobeareiter.wordpress.com/.

Many years ago a fateful meeting took place at Colonial Williamsburg,

ReplyDeleteColony of Virginia between the Faulkner family and the 4th Bn Royal

Regiment of Artillery 1776-1783. Jacqueline asked if she could join

our reenactment unit and was renamed Jack as no women were allowed to be gunners. Jack served with great distinction for three years until the family was posted back to England.

YMH & OS,

Ben Newton Capt Lt Royal Regiment of Artillery 1776-1783