As a specialist in Anglo-Saxon cultural history, I’ve found it immensely rewarding to explore the world of the early English peoples through the illustrated pages of their books. My favourite manuscript for doing this is the Old English Illustrated Hexateuch (see HERE for Part I of this article)

Getting down with the womenfolk

For my second detail from the Hexateuch, I want to focus on a particular ‘female’ skill, and in doing so throw something out there that may cause a stir. Now, I bet you’re thinking weaving, spinning or embroidery, aren’t you? Well, I’m not going there; instead we’re going to look at women as musicians.

When was the last time you saw in a ‘medieval’ film a woman playing a musical instrument in the feast hall? Whenever an Anglo-Saxon scop (musical poet) is called for, you just know it will be a male actor chosen. Now I’m not saying that women were employed as scops in Anglo-Saxon times – in reality, ‘professional’ scops were likely male, as is suggested by the poem Beowulf, in which the scop is depicted as part of the all-male comitatus, or band of warriors – but I am saying that the idea of women playing music is not alien to the Anglo-Saxon imagination. Take a gander at this picture of Miriam (the sister of Moses and Aaron, also known as Mary or Maria) and her women.

As you see, most of the women are playing something akin to the triangular harp. The Harley Psalter, produced in Canterbury around the same time as the Hexateuch, shows similar instruments. Note, too, that the woman on the far left is playing a smaller stringed instrument that resembles the lyre.

Now you might be thinking that the artist had to show the women playing their stringed instruments because that’s what it says in the Old English text. Indeed, the text states that they ‘took their harps (OE hearpe) in hand and praised and glorified God both with harp and with song (OE lofsang, literally ‘praise-song’)’. However, there’s more to it than that.

The Latin Vulgate text actually says that Miriam ‘took a timbrel (Lat. tympanum) in her hand: and all the women went forth after her with timbrels and with dances’ (Exodus 15:20). It would seem that the anonymous translator was unfamiliar with the timbrel, or tambourine, which was not yet introduced into Europe.

Unwise as it is here to be categorical, I will simply suggest that the translator substituted an instrument with which he was familiar, the harp, and which was familiar to him in the very context of contemporary women playing instruments. Furthermore, and rather fascinatingly, he didn’t seem to like the idea of women dancing and so instead he focuses on their instrument playing and singing.

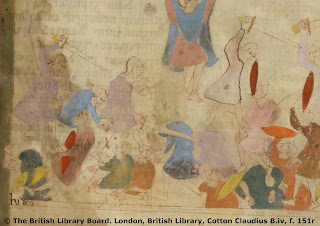

The artist apparently had no trouble in following the translator’s lead, though, remarkably, he also chose to make an additional contribution by depicting the men dancing, which is not described either in the Hexateuch text or the Latin Vulgate.

Perhaps what we are seeing here is a culturally acceptable interpretation of this biblical scene, and as a consequence we are shown that women in the late-Anglo-Saxon period could pick up their harp as well as their spindle!

Kicking the hell out of one another

Back to the men for my final insight from the Hexateuch. And what is it in Anglo-Saxon culture that men did best? All you living history performers know, don’t you? Yes, fighting, of course. Well my focus here is less on swordsmanship and valour, and rather more on getting the job done.

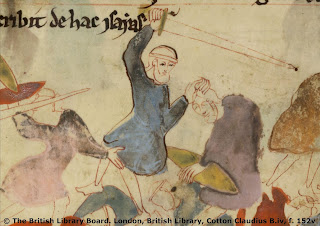

Take a look at Moses’ fighting technique. He’s just about to avenge a brother Israelite by slaying his killer, an Egyptian slave-driver (Exodus 2:11, 12). Now ignore the ridiculously big sword in Moses’ right hand and instead take a close look at his left hand and right foot.

Aha! It would seem that the best way to demobilise your enemy was to grab his beard, place your foot firmly and swiftly in his abdomen, and then dispatch the sword. None of this is described in either the Hexateuch or Vulgate texts, so it seems reasonable to suggest that the artist was drawing upon contemporary experience.

But wait, I hear you cry, the artist was a monk, so would likely not be conversant with fighting. That may be the case – though, it should be noted, monks came from all sorts of backgrounds, including in some cases a warrior one – but there is other evidence that may shed light on this.

The early Anglo-Saxon law of Ethelbert (c.600) refers to the ‘seizing of hair’ in the context of injuries from acts of violence, for which compensation had to be paid to the victim by the perpetrator. Now it may be that this law refers specifically to cutting off a man’s hair as a means of insulting him (the OE word used, feaxfang, literally means ‘hair-booty’), something that is referred to in the laws of Alfred the Great (reigned 871-899), where beard-cutting is also mentioned. Or it may simply mean that men grabbed other men’s hair when fighting.

In any case, it seems that seizing a man by his hair, or indeed his beard, may have been a common means of restraining a man in order to inflict violence upon him. Perhaps the monk artist had witnessed this mode of ‘street fighting’ and tapped into his personal recollection as a means of imagining Moses’ vengeance.

Certainly when we examine images of warfare in the Hexateuch, we can appreciate that the artist didn’t just stick with a neatly choreographed sword-and-shield technique, but, as you see in the next two images, went as far as depicting warriors trampling on the heads and bodies of their enemies and, yes, pulling hair – a reflection perhaps of the real mess of war.

Well I hope you’ve enjoyed this short foray into Anglo-Saxon art as a means of gaining insight into the lives of the peoples of early medieval England. There is so much more to be studied in the Old English Illustrated Hexateuch, in terms of cultural practices and items of everyday life: feasting, burying the dead and midwifery, for example; or baskets, buckets, wagons and farming tools, to name just a few objects.

A more thorough study of the art of this remarkable book would, I suggest, open up a finer reading of Anglo-Saxon culture alongside historical and archaeological records. Perhaps I should write a book about it...

Works consulted:

Graham Lawson and Susan Rankin, ‘Music’, and Graeme Lawson, ‘Musical Instruments’, from The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge et al. (Blackwell, 2001).

Gale R. Owen-Crocker, Dress in Anglo-Saxon England: Revised and enlarged edition (Boydell, 2004).

Dorothy Whitelock (ed.), English Historical Documents c. 500-1042 (Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1955).

Online:

Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: http://bosworth.ff.cuni.cz/

Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources: http://logeion.uchicago.edu/

Douay-Rheims Bible: http://www.drbo.org/

The Old English Illustrated Hexateuch: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/BriefDisplay.aspx: Just type ‘hexateuch’ into the search box.

Dr Christopher Monk taught for four years at the University of Manchester (UK) on subjects ranging from the language and history of Beowulf to sex and sexuality in Anglo-Saxon art. He now works as an independent consultant and development editor. Recently he was the medieval history and manuscript expert for a major permanent exhibition at Rochester Cathedral (due to open later in 2016) about one of Britain’s most important, but overlooked, medieval books, the twelfth-century Textus Roffensis. Chris continues to juggle scholarly work with creative writing. He has just published a chapter in a collection of essays about the Bayeux Tapestry, and has an eBook under review called Sodom in the Anglo-Saxon Imagination. But he’s also written a screenplay based in 1978 about a Kate Bush obsessive and is presently writing what he describes as “a sort of historical fantasy prequel to Beowulf”. He blogs as the transhistorical Anglo-Saxon Monk. Rounded Globe have just announced that they are to publish Christopher's study *Sodom in the Anglo-Saxon Imagination* as an eBook.

Dr Christopher Monk taught for four years at the University of Manchester (UK) on subjects ranging from the language and history of Beowulf to sex and sexuality in Anglo-Saxon art. He now works as an independent consultant and development editor. Recently he was the medieval history and manuscript expert for a major permanent exhibition at Rochester Cathedral (due to open later in 2016) about one of Britain’s most important, but overlooked, medieval books, the twelfth-century Textus Roffensis. Chris continues to juggle scholarly work with creative writing. He has just published a chapter in a collection of essays about the Bayeux Tapestry, and has an eBook under review called Sodom in the Anglo-Saxon Imagination. But he’s also written a screenplay based in 1978 about a Kate Bush obsessive and is presently writing what he describes as “a sort of historical fantasy prequel to Beowulf”. He blogs as the transhistorical Anglo-Saxon Monk. Rounded Globe have just announced that they are to publish Christopher's study *Sodom in the Anglo-Saxon Imagination* as an eBook.

Find him: At his website

and On his blog

What a fun post! Thanks!

ReplyDeleteGlad you enjoyed it Susan.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI really think you should write that book! Fascinating post.

ReplyDeleteI really think you should write that book! Fascinating post.

ReplyDeleteI'm very tempted to, Bev. Few other things before that, though. Glad you enjoyed the post.

ReplyDelete