Mankind has created pottery vessels for millennia, using whatever clay (earthen material that could be kneaded and shaped when damp) and heat source available to dry it. Porcelain has its roots in China going back as far at the 7th century during the Tang dynasty. The Yuan dynasty (13th-14th century) developed the hard paste porcelain as known today, combining white China clay (kaolin) with the dust of a finely ground rock called petuntse, which was then fired at extremely high heat (2650 degrees F). The Portuguese first visited Macao, a small peninsula on the southern coast of China in 1513 and visited regularly thereafter. After paying tribute to the Chinese, they established a trading post and began bringing goods from China and Japan, including Chinese porcelain, back to Europe.

Noting the superiority of porcelain over the pottery then used in European countries, Europeans then decided to recreate it in their own lands. The earliest recorded attempt was in Florence in 1575. France, Germany and England also made their efforts. In the 17th century, tea drinking became popular which resulted in increased importation of tea from China as well as the porcelain wares required for maximum enjoyment. The 18th century saw tremendous advances in Germany, France and England in the development of pottery forms similar to Chinese porcelain ware. Early in the 18th century, kaolin was discovered in Germany and delicate white porcelain was developed in Meissen, Germany. Throughout France and the other European countries, as well as England, efforts were being made to produce porcelain that was comparable to that produced by China. English factories could not easily access kaolin, so continued perfecting their soft paste porcelain, using materials they had at hand. English china became distinguished by the addition of ground ox bones to the formula, resulting in the well-known “bone china.”

John Wall was born in Powick, near Worcester, October 12, 1708. He studied at Worcester King’s School, won a scholarship to Worcester College Oxford, became a fellow at Merton College, Oxford in 1735, and qualified with a Batchelor of Physic at St. Thomas Hospital, London in 1736. He was qualified as a Doctor of Medicine (Medicinae Doctor or MD) in 1739. He returned to Worcester in 1740, married Catherine Sandys, and developed a vast practice.

Although a medical doctor of renown and fortune, Dr. Wall was interested in many things. In 1750, he and William Davis, an apothecary in Worcester, performed experiments in making porcelain with soapstone (a form of granite, also known as steatize granite).

.jpg) |

| Dr. John Wall, 18th Century |

During the first decade of its existence, the most popular Worcester Porcelain was painted in blue then glazed. An engraver named Robert Hancock arrived at the factory about 1756 and, with his expertise with engraving prints, Worcester Porcelain factory developed the use of transfers to print designs on porcelain and produced porcelain so decorated on a large scale, which provided employment to a significant number of people. Around 1770, Worcester Porcelain produced a dinner service for the Duke of Gloucester. In 1774, Dr. Wall retired. The partners continued the production of porcelain. The factory was purchased by Thomas Flight, who had acted as the factory’s London agent, and became established as one of the most prominent porcelain manufacturers in Europe. George III granted the factory a Royal Warrant in 1789, at which time the word “Royal” was added to the name. The factory became known at the Worcester Royal Porcelain Manufactory, also known as Royal Worcester.

.jpg/800px-Cup_(AM_1945.117-2).jpg) |

| Cup 1755-1790, Auckland Museum |

|

| Royal Worcester Tea Caddy 1770 |

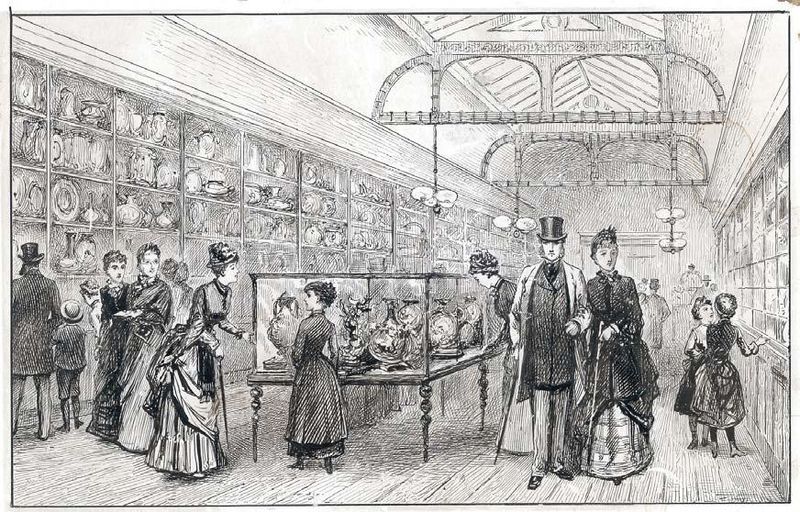

Worcester Royal Porcelain remained popular throughout the Victorian era, producing services for the royal family and others. The company name was changed to Worcester Royal Porcelain Company Ltd. in 1862. Throughout its history, the company changed ownership and design direction several times without loss of quality. At its height, the factory provided employment to over 700 people. The company’s products were highly regarded and maintained popularity well into the 20th century. In 1976, Worcester Royal merged with W. T. Copeland to become Royal Worcester Spode. While its porcelain maintained its popularity with high end customers, it began to struggle and, in the late 20th-early 21st century, began attempting a more mass market appeal by producing comedy mugs and other departures. By 2006, work in England was being performed in Stoke-on-Trent instead of Worcester, and production was outsourced abroad.

|

| Royal Worcester Factory Museum before 1900 |

In November of 2008, the economic downturn combined with the company’s failure to find a buyer led to the company being placed under a court-appointed administrator whose job was to leverage the company’s assets to repay creditors and avoid insolvency. On April 23, 2009, Worcester Royal Porcelain was acquired by an English firm, Portmeirion Pottery, which is now known as Portmeirion Group. In Worcester, visitors can spend time at the Museum of Royal Worcester to learn about the history of the factory and see the products and films of work in process from the 1930’s until the end. The archives there hold a range of information, including pattern books and order records.

Sources include:

BBC. “HEREFORD & WORCESTER A History of Royal Worcester Porcelain.” HERE

Collector’s Weekly. “Royal Worcester China.” HERE

Britannica.com “Porcelain” by the Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. HERE ; “Macau” by the editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. HERE

GourmetSleuth. “Royal Worcester History.” HERE

Hektoen International. “Dr. John Wall and Royal Worcester Porcelain” by JMS Pearce, Summer 2018. HERE

History World. “HISTORY OF POTTERY AND PORCELAIN The European Quest for Porcelain: 16th-18th Century.”HERE

Museum of Royal Worcester. “Dr. John Wall.” HERE

The Telegraph. “A History of Royal Worcester and Spode” published November 6, 2008.HERE ; “Royal Worcester collapses after 257 years making China” by Nick Britten, published November 6, 2008. HERE

Wikisource. 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Volume 5. “Ceramics.” HERE

All illustrations from Wikimedia Commons:

Dr. John Wall HERE (Public Domain)

Coffee Cup c 1755-1790, by Auckland Museum [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)] HERE

Royal Worcester Tea Caddy c1770 HERE (Public Domain-Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Lauren Gilbert holds a BA in English with a minor in Art History, and is a long-time member of the Jane Austen Society of North America. She published HEYERWOOD: A Novel in 2011, and is in the process of completing a second novel while doing research for a nonfiction work. She is a member of the Florida Writers Association and the Society of Authors. Lauren lives in Florida with her husband Ed. You may visit her website here for more information.

Lauren Gilbert holds a BA in English with a minor in Art History, and is a long-time member of the Jane Austen Society of North America. She published HEYERWOOD: A Novel in 2011, and is in the process of completing a second novel while doing research for a nonfiction work. She is a member of the Florida Writers Association and the Society of Authors. Lauren lives in Florida with her husband Ed. You may visit her website here for more information.

Very informative post. Thanks, Lauren. My ancestors collected porcelain.

ReplyDeleteI appreciate the comment, Roland. Porcelain is a fascinating subject. I have a few pieces myself.

Delete