by Matthew Harffy

Bamburgh Castle, equally magnificent and forbidding, sits atop its crag, overlooking the windswept, slate-grey North Sea. Despite appearances, it is now an extensively rebuilt edifice, having been remodeled by Victorian industrialist William Armstrong.

But 1,400 years ago, it was Bebbanburg, cliff-top fortress of the kings of Bernicia, the northern kingdom of what would become Northumbria.

The first half of the seventh century is situated deep in what has traditionally been called The Dark Ages. The period is dark in many ways. It was a violent time, where races clashed and kingdoms were created and destroyed by the sword.

Men with ambition ruled kingdoms with their small retinues of warrior companions. These leaders professed kingship tracing back their claims through ancestors all the way to the ancient gods themselves. But I imagine them to be like gangsters, or the cattle barons of the American West of the nineteenth century. Each vied for dominance over an untamed land, clashing with other kings in battles which were little more than turf wars. They exacted payment in tribute from the peasants that lived on their land. This was basically protection money to keep the king and his retinue stocked up with weapons, food and luxuries, so that they would be at hand to defend the populace against the dangers of a largely lawless land.

Throw into this mix racial tensions and the expansion of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes from the east of Britain, enslaving and subjugating the older inhabitants of the island, the native Britons, and you have a situation not unlike the American “Wild West”. Invaders from the east, with superior fighting power destroying a proud culture that inhabited the land long before they came. As the Anglo-Saxons pushed further westward, there would inevitably have been a frontier where any semblance of control from the different power factions was weak at best and at worst, totally absent. As in the Wild West of cowboys and Native Americans, men and women who wished to live outside of the law would have gravitated into these vacuums of power.

This period also sees the clash of several major religions. Many of the native Britons would worship the same gods they had believed in for centuries, whilst others worshipped Christ; the Angles and Saxons were just beginning to be converted to Christianity, but many still worshipped the old pantheon of Woden and Thunor (more commonly known to modern readers with the Norse names of Odin and Thor).

Christianity itself was being evangelised from two main power bases: the island of Iona, where the Irish tradition had taken root, and Rome, from where Italian priests, such as Paulinus had been sent. Christianity would eventually sweep all other religions away before it, and the disagreements on the some of the finer points of theology that divided the two factions would later be settled at the Synod of Whitby in 664.

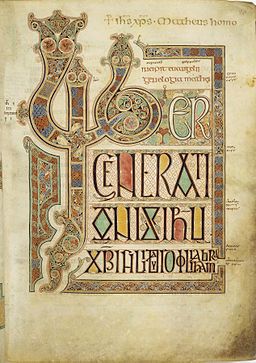

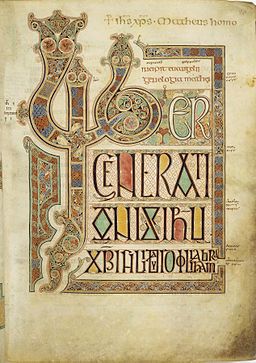

Perhaps the term “Dark Ages” has stuck because of the lack of first-hand written accounts of the period. Much of what we know comes from two principal sources: Bede’s “A History of the English Church and People” and the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle”, which was written by many nameless scribes over centuries. It is a time seen as "through a glass, darkly", but despite the battles and violence, the struggles of warriors and kings, it is also a period when items of great beauty were created. Christianity would soon flourish, and, over the next century, before the coming of the dreaded Vikings, Northumbria entered into a Golden Age, which saw the creation of fabulous books, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels, and works of exquisite craftsmanship.

What was it like to walk, breathe, live, love and die in that faraway time and place? We shall never know. And how should we remember that distant part of Britain’s history? As the Dark Ages? As an embattled frontier akin to the American West? Or perhaps even as a Golden Age of illuminations, learning and fine art?

In the end, I believe the answer is probably that it was all of these things and more.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Matthew Harffy lived in Northumberland as a child and the area had a great impact on him. The rugged terrain, ruined castles and rocky coastline made it easy to imagine the past. Decades later, a documentary about Northumbria's Golden Age sowed the kernel of an idea for a series of historical fiction novels. The first is the action-packed tale of vengeance and coming of age, The Serpent Sword. The reduced price of the book is running until the end of Saturday, June 6.

He is currently working on the sequel, The Cross and The Curse.

The Serpent Sword is available on Amazon.

Website: www.matthewharffy.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MatthewHarffy/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MatthewHarffyAuthor

Bamburgh Castle, equally magnificent and forbidding, sits atop its crag, overlooking the windswept, slate-grey North Sea. Despite appearances, it is now an extensively rebuilt edifice, having been remodeled by Victorian industrialist William Armstrong.

But 1,400 years ago, it was Bebbanburg, cliff-top fortress of the kings of Bernicia, the northern kingdom of what would become Northumbria.

The first half of the seventh century is situated deep in what has traditionally been called The Dark Ages. The period is dark in many ways. It was a violent time, where races clashed and kingdoms were created and destroyed by the sword.

Men with ambition ruled kingdoms with their small retinues of warrior companions. These leaders professed kingship tracing back their claims through ancestors all the way to the ancient gods themselves. But I imagine them to be like gangsters, or the cattle barons of the American West of the nineteenth century. Each vied for dominance over an untamed land, clashing with other kings in battles which were little more than turf wars. They exacted payment in tribute from the peasants that lived on their land. This was basically protection money to keep the king and his retinue stocked up with weapons, food and luxuries, so that they would be at hand to defend the populace against the dangers of a largely lawless land.

Throw into this mix racial tensions and the expansion of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes from the east of Britain, enslaving and subjugating the older inhabitants of the island, the native Britons, and you have a situation not unlike the American “Wild West”. Invaders from the east, with superior fighting power destroying a proud culture that inhabited the land long before they came. As the Anglo-Saxons pushed further westward, there would inevitably have been a frontier where any semblance of control from the different power factions was weak at best and at worst, totally absent. As in the Wild West of cowboys and Native Americans, men and women who wished to live outside of the law would have gravitated into these vacuums of power.

This period also sees the clash of several major religions. Many of the native Britons would worship the same gods they had believed in for centuries, whilst others worshipped Christ; the Angles and Saxons were just beginning to be converted to Christianity, but many still worshipped the old pantheon of Woden and Thunor (more commonly known to modern readers with the Norse names of Odin and Thor).

Christianity itself was being evangelised from two main power bases: the island of Iona, where the Irish tradition had taken root, and Rome, from where Italian priests, such as Paulinus had been sent. Christianity would eventually sweep all other religions away before it, and the disagreements on the some of the finer points of theology that divided the two factions would later be settled at the Synod of Whitby in 664.

Perhaps the term “Dark Ages” has stuck because of the lack of first-hand written accounts of the period. Much of what we know comes from two principal sources: Bede’s “A History of the English Church and People” and the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle”, which was written by many nameless scribes over centuries. It is a time seen as "through a glass, darkly", but despite the battles and violence, the struggles of warriors and kings, it is also a period when items of great beauty were created. Christianity would soon flourish, and, over the next century, before the coming of the dreaded Vikings, Northumbria entered into a Golden Age, which saw the creation of fabulous books, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels, and works of exquisite craftsmanship.

What was it like to walk, breathe, live, love and die in that faraway time and place? We shall never know. And how should we remember that distant part of Britain’s history? As the Dark Ages? As an embattled frontier akin to the American West? Or perhaps even as a Golden Age of illuminations, learning and fine art?

In the end, I believe the answer is probably that it was all of these things and more.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Matthew Harffy lived in Northumberland as a child and the area had a great impact on him. The rugged terrain, ruined castles and rocky coastline made it easy to imagine the past. Decades later, a documentary about Northumbria's Golden Age sowed the kernel of an idea for a series of historical fiction novels. The first is the action-packed tale of vengeance and coming of age, The Serpent Sword. The reduced price of the book is running until the end of Saturday, June 6.

He is currently working on the sequel, The Cross and The Curse.

The Serpent Sword is available on Amazon.

Website: www.matthewharffy.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MatthewHarffy/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MatthewHarffyAuthor

A fascinating era indeed and what a great comparison! The Wild West - and like the Native Americans, the Britons lost. It seems also to be a great era for the various saints with the unpronounceable names. ;-)

ReplyDeletePS Bamburgh Caste has been used quite a lot in historical films/TV shows. It's quite spectacular, isn't it?

ReplyDeleteIt is a fascinating era, Sue! Thanks for taking the time to leave a comment.

ReplyDeleteThe names are difficult, but the period is ripe for a novelist. So much happening and so much unknown! :-)

Makes you think differently about the lawless states today. When you hear areas of Afghanistan,Yemen, or Somalia, we tend to forget that our own country was once ruled by local warlords, gangsters and cattle barons described in this article.

ReplyDelete