by Margaret Porter

Oft have I heard both youth and virgins sayOrigins.

Birds choose their mates, and couple too this day;

But by their flight I never can divine

When I shall couple with my Valentine.

--Robert Herrick

In ancient Rome on 15th February, young men drew young women's names in honour of the goddess Februata-Juno. After Christianity was established, the church replaced the pagan ritual and chose the preceding day to venerate St Valentine of Rome.

|

| Valentine's baptism of St Lucilla by Jacopo Bassano |

Archaeologists discovered evidence of his existence in a Roman catacomb and found the remains of an ancient church dedicated to him. In 496, to honour his martyrdom, Pope Gelasius designated 14th February as his saint's day. Valentine remains on the Roman Catholic list of saints, although he was de-listed from veneration in 1969. Within the Anglican Communion 14th February is an official feast day. He is the patron saint of lovers, engaged persons, and happily married couples--but also bee keepers, travellers, and those suffering from epilepsy, fainting, and plague.

England

During the Middle Ages in England it was believed that birds choose their mates in mid-February. In 1361 Chaucer aligns this belief with observance of the saint, in his poem The Parliament of Fowls, commemorating the marriage of King Richard II and Anne of Bohemia:

For this was on Seynt Valentynes day,

Whan every foul cometh ther to chese his make,

...

This noble emperesse, ful of grace,

Bad every foul to take his owne place,

As they were wont alwey fro yeer to yere,

Seynt Valentynes day, to stonden there.

On the 14th it was customary for young men to draw names from a bowl as a way of choosing a female valentine. A paper bearing that person's name was attached to the sleeve. Thus, the phrase "wear your heart on your sleeve" is very old indeed! The drawing of valentines crossed social boundaries, so in the traditional lottery a maid might draw her master's name.

|

| Henry VIII in 1537, by Holbein |

It was popularly believed that the first person an individual met on that day (though not a family member) would be their Valentine, and if you were choosy you would keep your eyes shut until an acceptable prospect materialised. Shakespeare's Ophelia expresses her desire to be the first person Hamlet sees in the morning, with this rhyme,

To morrow is Saint Valentine'sVarious forms of prognostication arose. To know the occupation of her future husband, a girl would look to the skies. If she saw a blackbird, he'd be a clergyman; a robin meant a sailor; a goldfinch indicated a rich man; a blue tit predicted a happy man; a crossbill, an argumentative man; a dove for a good man. If she saw a woodpecker, she'd have no man at all.

All in the morning betime

And I a maid at your window

To be your Valentine

She might also place a single bay leaf beneath her pillow, reciting, "Saint Valentine, be kind to me, This night may I my true love see."

It was bad luck to bring snowdrops into the house on Valentine's, or else the girls dwelling there will never be wed.

In a Leap Year, girls were permitted to propose marriage to bachelors on Valentine's Day as well as on the 29th of February.

17th Century

|

| 17h Century glove |

Good morrow, Valentine, I go today

To wear for you what you must pay.

A pair of gloves next Easter Day.

According to Monsieur Misson, a French visitor to England, the drawing of names continued to be popular:

On the Eve of the 14th of February, St Valentine's Day, an equal Number of Maids and Batchelors get together each writes their true or some feign'd Name upon separate Billets which they roll up and draw by way of Lots, the Maids taking the Men's Billets and the Men the Maids' so that each of the young Men lights upon a Girl that he calls his Valentine and each of the Girls upon a young Man which she calls hers. By this Means each has two Valentines but the Man sticks faster to the Valentine that is fallen to him than to the Valentine to whom he is fallen. Fortune having thus divided the Company into so many Couples, the Valentines give Balls and Treats to their Mistresses, wear their Billets several Days upon their Bosoms or Sleeves, and this little Sport often ends in Love.

|

| Samuel Pepys by Peter Lely |

Valentine's Day was also an opportunity for pranks and frolic, and some of the best evidence of Valentine's Day merriment, expectations, and expence comes from diarist Samuel Pepys:

Thursday, 14th February 1661

14th (Valentine's day). Up early and to Sir W. Batten's, but would not go in till I asked whether they that opened the door was a man or a woman, and Mingo, who was there, answered a woman, which, with his tone, made me laugh; so up I went and took Mrs. Martha for my Valentine (which I do only for complacency), and Sir W. Batten he go in the same manner to my wife, and so we were very merry.

Friday, 14th February 1662

14th (Valentine's day). I did this day purposely shun to be seen at Sir W. Batten's, because I would not have his daughter to be my Valentine, as she was the last year, there being no great friendship between us now, as formerly. This morning in comes W. Bowyer, who was my wife's Valentine, she having, at which I made good sport to myself, held her hands [over her eyes] all the morning, that she might not see the paynters that were at work in gilding my chimney-piece and pictures in my diningroom.

Tuesday, 14th February 1665

14th (St. Valentine). This morning comes betimes Dicke Pen, to be my wife's Valentine, and come to our bedside. By the same token, I had him brought to my side, thinking to have made him kiss me; but he perceived me, and would not; so went to his Valentine: a notable, stout, witty boy. I up about business, and, opening the door, there was Bagwell's wife, with whom I talked afterwards, and she had the confidence to say she came with a hope to be time enough to be my Valentine, and so indeed she did,

Wednesday, 14th February 1666

14th (St. Valentine's day). This morning called up by Mr. Hill, who, my wife thought, had been come to be her Valentine; she, it seems, having drawne him last night, but it proved not. However, calling him up to our bed-side, my wife challenged him.

Thursday, 14 February 1667

This morning come up to my wife’s bedside, I being up dressing myself, little Will Mercer to be her Valentine; and brought her name writ upon blue paper in gold letters, done by himself, very pretty; and we were both well pleased with it. But I am also this year my wife’s Valentine, and it will cost me £5; but that I must have laid out if we had not been Valentines.

Saturday, 16 February 1667

I find Mrs. Pierce’s little girl is my Valentine, she having drawn me; which I was not sorry for, it easing me of something more that I must have given to others. But here I do first observe the fashion of drawing of mottos as well as names; so that Pierce, who drew my wife, did draw also a motto, and this girl drew another for me. What mine was I have forgot; but my wife’s was, “Most virtuous and most fair;” which, as it may be used, or an anagram made upon each name, might be very pretty.

Friday, 14th February 1668

14th (Valentine's day). Up, being called up by Mercer, who come to be my Valentine, and so I rose and my wife, and were merry a little, I staying to talk, and did give her a guinny [guinea] in gold for her Valentine's gift. There comes also my cozen Roger Pepys betimes, and comes to my wife, for her to be his Valentine, whose Valentine I was also, by agreement to be so to her every year; and this year I find it is likely to cost £4 or £5 in a ring for her, which she desires.

18th Century

|

| 18th century puzzle valentine |

At the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, Valentine's Day: A Musical Drama in Two Acts was performed as an afterpiece in 1776. It sounds as though it would be a delightful entertainment, however a theatre employee recorded in his diary that it was "much hissed" and "badly performed." The critics were a little kinder:

It would be going out of our way to dwell much on its defects; suffice it therefore that although we so far join with the audience in condemnation of it...yet we protest we have seen worse singing pieces received with applause. Jerry Jingle had some humour, and the music had great prettiness about it. (Westminster Magazine)For a sixpence, a young woman seeking inspiration could purchase the book Every Lady's Own Valentine Writer In Prose and Verse for 1798 contained "Humorous Dialogue: Witty Valentines, with Answers; Pleasant Sonnets, on Love, Courtship, Marriage, Beauty, &c&c". The first entry is a dramatic sketch set in a girls' boarding school, in which several pupils compare their gifts--a cake, a diamond pin, a work-bag, all accompanied with a rhyme--which appear all to have come from the same young man.

Most of the romantic poems it contains are written in the form of a question or plea from the swain, immediately followed by a set of rhymed verses from the lady, giving her answer.

Here is a sample acrostic featured in the book:

V ain world farewell, I live for love

A mbition ne'er my soul shall move;

L ove is the all of my desire,

E ach thought, each wish, it can inspire;

N e'er can wealth my hopes excite;

T itles are mere trifles light;

I n a sound there's no delight.

N ames can never joy assign,

E xcept that of Valentine.

19th Century

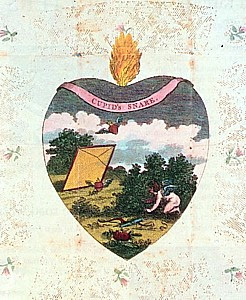

|

| Regency Valentine |

In his Essays of Elia, Charles Lamb discourses upon the holiday :

...this is the day on which those charming little missives, ycleped Valentines, cross and intercross each other at every street and turning. The weary and all forspent twopenny postman sinks beneath a load of delicate embarrassments, not his own. It is scarcely credible to what an extent this ephemeral courtship is carried on in this loving town, to the great enrichment of porters, and detriment of knockers and bell-wires....Not many sounds in life, and I include all urban and all rural sounds, exceed in interest a knock at the door. It “gives a very echo to the throne where Hope is seated.” ...But of all the clamorous visitations the welcomest in expectation is the sound that ushers in, or seems to usher in, a Valentine.

|

| Victorian Valentine |

Impetuous reckless use of a valentine purchased in a shop leads to a crucial aspect of plot in Thomas Hardy's novel Far From the Madding Crowd:

It was Sunday afternoon in the farmhouse, on the thirteenth of February. Dinner being over, Bathsheba, for want of a better companion, had asked Liddy to come and sit with her....

"Dear me--I had nearly forgotten the valentine I bought yesterday," she exclaimed at length.

"Valentine! who for, miss?" said Liddy. "Farmer Boldwood?"

It was the single name among all possible wrong ones that just at this moment seemed to Bathsheba more pertinent than the right.

"Well, no. It is only for little Teddy Coggan. I have promised him something, and this will be a pretty surprise for him. Liddy, you may as well bring me my desk and I'll direct it at once."

Bathsheba took from her desk a gorgeously illuminated and embossed design in post-octavo, which had been bought on the previous market-day at the chief stationer's in Casterbridge. In the centre was a small oval enclosure; this was left blank, that the sender might insert tender words more appropriate to the special occasion than any

generalities by a printer could possibly be.

"Here's a place for writing," said Bathsheba. "What shall I put?"

"Something of this sort, I should think," returned Liddy promptly: --

"The rose is red,

The violet blue,

Carnation's sweet,

And so are you."

"Yes, that shall be it. It just suits itself to a chubby-faced child like him," said Bathsheba. She inserted the words in a small though legible handwriting; enclosed the sheet in an envelope, and dipped her pen for the direction.

"What fun it would be to send it to the stupid old Boldwood, and how he would wonder!" said the irrepressible Liddy, lifting her eyebrows, and indulging in an awful mirth on the verge of fear as she thought of the moral and social magnitude of the man contemplated....

"No, I won't do that. He wouldn't see any humour in it."

But of course, she does. And he doesn't. A Valentine's joke that goes seriously awry!

Nowadays, as we express our affections with cards and flowers and chocolates, in social media as well as via the postal service, we perpetuate time-tested traditions that our most distant ancestors would recognise.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Margaret Porter is the award-winning and bestselling author of twelve period novels, whose other publication credits include nonfiction and poetry. A Pledge of Better Times, her highly acclaimed novel of 17th century courtiers Lady Diana de Vere and Charles Beauclerk, 1st Duke of St. Albans, is her latest release, available in trade paperback and ebook. Margaret studied British history in the UK and the US. As historian, her areas of speciality are social, theatrical, and garden history of the 17th and 18th centuries, royal courts, and portraiture. A former actress, she gave up the stage and screen to devote herself to fiction writing, travel, and her rose gardens.

Author Website

Blog

Author Page

Lovely!

ReplyDeleteFascinating.

ReplyDeleteThank you! So glad you enjoyed it.

ReplyDeleteA delightful and interesting post. I love the idea of gloves being a gift. Thank you!

ReplyDeleteMany thanks, and thanks for sharing!

DeleteWhat a lovely post. Thank you :-)

ReplyDeleteMarvelous post and wonderfully illustrated! It adds so much to the tragedy that the card, what Boldwood, bases his all on ,was a joke and that Bathsheba knew he would take it seriously,yet sent it anyway.

ReplyDeleteAnother great Valentine story is how in Feb 1840 Willy Wightman, Haworth curate,trampled the ten miles to Bradford so the Bronte girls and friend,Ellen Nussey, would each receive a Valentine from beyond the village. Not a small thing by any means. He was known for winning hearts and even today one has to love Willy Wightman for that hike to Bradford

I'd never heard that story about Willy Wightman, Anne. Very touching.

ReplyDeleteEntertaining post, Margaret. The Regency Valentine is beautiful!