by Maria Grace

Unlike the wedding ceremony, friends and relatives were usually invited to the wedding breakfast. Sometimes, though, the bride and groom set off for the post-nuptial travels immediately from the church door, leaving their loved ones to celebrate on their own.

With all the alcohol, wedding cakes kept for a long time. Pieces would be sent home with family and friends, delivered to neighbors and even send over distances to those who could not be part of the celebrations.

Since the war (and finances for most people) made touring the continent out of the question, couples of the era usually planned trips closer to home. They might visit relations to make introductions (and cut down on travel costs) or visit picturesque landscapes like the Lake District or Peaks or seaside resorts like Brighton.

Often, the bride's sister or closest female friend accompanied the couple. To the modern eye the custom seems weird at best, but since the bride and groom might have spent little time alone with one another prior to the wedding, relying only on one another for conversation and company could be very awkward. Having another person along could ease the transition for everyone.

Austen -Leigh, Mary Augusta. Personal Aspects Of Jane Austen. London John Murray, Albemarle Street. 1920.

Book of Common Prayer. Imprinted at London: By Robert Barker ..., 1632. Book of Common Prayer

Forsling, Yvonne. Weddings During the Regency https://www.janeausten.co.uk/weddings-during-the-regency-era/ Accessed 7/24/2016

Forsling, Yvonne . Regency Weddings: Fashion Periodicals http://hibiscus-sinensis.com/regency/weddingprints.htm Accessed 7/20/2016

Jones, Hazel. Jane Austen and Marriage. London: Continuum, 2009.

Kane, Kathryn. "Marriage Lines" really are lines! 19 December 2008 https://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2008/12/19/marriage-lines-really-are-lines/

Laudermilk, Sharon H., and Teresa L. Hamlin. The Regency Companion. New York: Garland, 1989.

Raffald, Elizabeth. The Experienced English Housekeeper for the Use and Ease of Ladies, Housekeepers, Cooks, &c. Written Purely from Practice ... Consisting of near Nine Hundred Original Receipts, Most of Which Never Appeared in Print. ... The Tenth Edition. ... By Elizabeth Raffald. London: Printed for R. Baldwin, 1786.

Reeves-Brown, Jessamyn. Regency Wedding Details & History http://www.songsmyth.com/weddings.html. Accessed 7/25/16

Sanborn, Vic. And the Bride Wore… June 17, 2011. https://www.janeausten.co.uk/and-the-bride-wore/. Accessed 7/26/16

Wilson, Carol. Gastronomica: The Journal Of Food And Culture, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 69–72, issn 1529-3262.

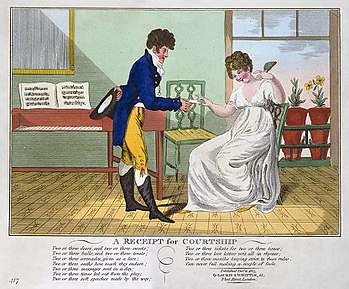

To Have a Courtship, One Needs a Suitor

Nothing is ever that simple: Rules of Courtship

Show me the Money: the Business of Courtship

The Price of a Broken Heart

Making an Offer of Marriage

Games of Courtship

The Hows and Why of Eloping

Licenses, Laws and Legalities of Marriage

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was ten years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful. After penning five file-drawer novels in high school, she took a break from writing to pursue college and earn her doctorate. After 16 years of university teaching, she returned to her first love, fiction writing.

Click here to find her books on Amazon. For more on her writing and other Random Bits of Fascination, visit her website. You can also like her on Facebook, follow on Twitter or email

Today’s brides may spend a year or more planning a wedding. Having a dress made, planning the reception in every detail and the cake—oh the cake!—are the stuff of many a young woman’s dreams. So much so, discovering the details of a Regency era wedding might turn out a bit disappointing since most of the elaborate traditions we associate with weddings today originated decades later, during the Victorian Era.

Wedding Dress

Modern brides often spend a great deal of attention and money on the wedding dress and expect to wear it only once. Honestly, it is hard to imagine another event where wearing one’s wedding dress might be appropriate. Not exactly the sort of thing you’d wear to dinner, right?

In the regency era, though, the cost of textiles was so prohibitive that only royals like Princess Charlotte and equally wealthy brides even considered dresses that might only be worn once. So, a bride, wore her ‘best dress’ for her wedding. A bride with some means, might have a new ‘best dress’ made for the occasion.

What might this ‘best dress’ look like? Typically it would not be white. White garments required a huge amount of upkeep in an era where all wash was done by hand, so only the wealthiest wore it. Colored gowns were typical, with yellow, blue, pink and green being popular for several regency era years. Middle and lower class brides often chose black, dark brown and burgundy as practical colors that would wear well for years to come.

Fashion plates from Ackerman’s and La Belle Assemblee illustrate gowns used for weddings. All though all these gowns are white, that is more indicative of the white gown being the ‘little black dress’ of the era, rather than white being the wedding color.

Fashion plates from Ackerman’s and La Belle Assemblee illustrate gowns used for weddings. All though all these gowns are white, that is more indicative of the white gown being the ‘little black dress’ of the era, rather than white being the wedding color.

All these gowns followed the fashionable trends of formal gowns of the day, but were largely indistinguishable from other formal gowns, attested to by the La Belle Assemblee dress being cited as both an evening dress and a wedding dress. Finer materials might be utilized if the bride could afford: silks, satins and lace. The trims might be altered for wear after the wedding.

None of these fashion plate brides wore a veil. That fashion, though common in France, would not take hold in England until the Victorian era. Caps, hats, bonnets or flowers in the hair were common though.

“Since wedding gowns were often worn - to the point of being worn out - after the wedding, brides had to cherish something else. Often this was one of her wedding shoes, a natural choice given the lucky connotations of shoes in this context. Many carefully preserved satin slippers remain with notes inscribed in the instep attesting to the wearer's wedding.” (Reeves-Brown)

The newspaper announcement, in both a national and local newspaper was, arguably, the most socially important facet of the wedding. “Jane Austen once wrote, ‘The latter writes me word that Miss Blackford is married, but I have never seen it in the papers, and one may as well be single if the wedding is not to be in print.’” (Forsling, Weddings During the Regency.)Sometimes the announcements did not even give the name of the bride, just her father’s name—and any titled connections, because who would dare forget them?

All weddings, except those by special license, took place between 8 AM and noon. (The reasons? Honorable people had nothing to fear in the light of day and people would be more serious in the morning.) Any day of the week was acceptable, though Sundays might be a bit inconvenient. Certain holy days, especially Lent were traditionally avoided.

Most people walked to church instead of riding in a carriage. Of course, most people did not have a carriage to ride in either. Flowers, herbs or rushes might be scattered on the route or at the church porch.

As with many weddings today, the bride’s father (if present) would present the bride to the groom. The vows would be read from the Book of Common Prayer and a wedding ring, or rings exchanged.

Interestingly, ring or rings were integral to the ceremony and it could not take place without them. The rings could be plain or ornate, precious metals like gold, or less dear materials like brass. “Lord Byron claimed that the wedding ring was 'the damnedest part of matrimony' but married men wore them as often as not, engraved with the couple's initials and the date of union.” (Jones, 2009)

A copy of the records would be made and signed by all participants in the ceremony. The marriage lines would then be given to the new bride, notably her property, not the groom’s.

Why?

In the regency era, though, the cost of textiles was so prohibitive that only royals like Princess Charlotte and equally wealthy brides even considered dresses that might only be worn once. So, a bride, wore her ‘best dress’ for her wedding. A bride with some means, might have a new ‘best dress’ made for the occasion.

What might this ‘best dress’ look like? Typically it would not be white. White garments required a huge amount of upkeep in an era where all wash was done by hand, so only the wealthiest wore it. Colored gowns were typical, with yellow, blue, pink and green being popular for several regency era years. Middle and lower class brides often chose black, dark brown and burgundy as practical colors that would wear well for years to come.

Fashion plates from Ackerman’s and La Belle Assemblee illustrate gowns used for weddings. All though all these gowns are white, that is more indicative of the white gown being the ‘little black dress’ of the era, rather than white being the wedding color.

Fashion plates from Ackerman’s and La Belle Assemblee illustrate gowns used for weddings. All though all these gowns are white, that is more indicative of the white gown being the ‘little black dress’ of the era, rather than white being the wedding color.All these gowns followed the fashionable trends of formal gowns of the day, but were largely indistinguishable from other formal gowns, attested to by the La Belle Assemblee dress being cited as both an evening dress and a wedding dress. Finer materials might be utilized if the bride could afford: silks, satins and lace. The trims might be altered for wear after the wedding.

None of these fashion plate brides wore a veil. That fashion, though common in France, would not take hold in England until the Victorian era. Caps, hats, bonnets or flowers in the hair were common though.

“Since wedding gowns were often worn - to the point of being worn out - after the wedding, brides had to cherish something else. Often this was one of her wedding shoes, a natural choice given the lucky connotations of shoes in this context. Many carefully preserved satin slippers remain with notes inscribed in the instep attesting to the wearer's wedding.” (Reeves-Brown)

Groom’s Attire

Men’s formal attire, not unlike today, was fairly well established, largely due to the influence of Beau Brummell. White shirts of muslin or linen, with a white cravat, ideally in silk. A black or dark cut away, tailed jacket, with buttons left open to show a waistcoat. (Although some period reports note grooms in light colored suits as well.) The waistcoat might be brightly colored and richly embroidered, the one place on a man’s ensemble where bright colors were widely acceptable. Dark or black knee breeches, skin tight of course! Loose fitting trousers were generally not acceptable for a formal occasion until the later part of the regency. Black stockings and black pumps, never boots, and a top hat would finish the ensemble.Invitations and Announcements

Unlike weddings today, the wedding ceremony was not a widely attended event. Obviously the bride and groom, along with their witnesses, usually the bridesmaid and groomsman and the clergyman were there. Close family might be there and possibly local close friends, but that was all. People did not generally travel to attend a wedding, so few if any invitations were issued. Neighbors and other well-wishers would not attend the service, but might wait outside the church for the couple to emerge.The newspaper announcement, in both a national and local newspaper was, arguably, the most socially important facet of the wedding. “Jane Austen once wrote, ‘The latter writes me word that Miss Blackford is married, but I have never seen it in the papers, and one may as well be single if the wedding is not to be in print.’” (Forsling, Weddings During the Regency.)Sometimes the announcements did not even give the name of the bride, just her father’s name—and any titled connections, because who would dare forget them?

Ceremony

Regency era wedding ceremonies were simple and entirely determined by the prescribed service in the Book of Common Prayer. The only requirements were the clergyman, parish clerk to ensure formal logging in the register, and two witnesses.All weddings, except those by special license, took place between 8 AM and noon. (The reasons? Honorable people had nothing to fear in the light of day and people would be more serious in the morning.) Any day of the week was acceptable, though Sundays might be a bit inconvenient. Certain holy days, especially Lent were traditionally avoided.

Most people walked to church instead of riding in a carriage. Of course, most people did not have a carriage to ride in either. Flowers, herbs or rushes might be scattered on the route or at the church porch.

As with many weddings today, the bride’s father (if present) would present the bride to the groom. The vows would be read from the Book of Common Prayer and a wedding ring, or rings exchanged.

Interestingly, ring or rings were integral to the ceremony and it could not take place without them. The rings could be plain or ornate, precious metals like gold, or less dear materials like brass. “Lord Byron claimed that the wedding ring was 'the damnedest part of matrimony' but married men wore them as often as not, engraved with the couple's initials and the date of union.” (Jones, 2009)

Marriage lines

After the ceremony, the clergyman, parish clerk, bride, groom, and two witnesses would proceed to the vestry to enter the ‘marriage lines’ into the parish register book. These ‘lines’ were explicitly set out in the Hardwicke Act and constituted the official record of the wedding, legal proof that it had taken place.A copy of the records would be made and signed by all participants in the ceremony. The marriage lines would then be given to the new bride, notably her property, not the groom’s.

Why?

“Proof of her married state was much more important to a woman than to a man. Particularly among … the lower classes, a woman’s social standing, in some cases her very survival, depended upon her ability to prove she was a respectable married woman. …A woman who was thought to be living with a man without benefit of clergy could be exposed to any number of dangers. She could not depend on her husband for support if she could not prove she was his legal wife, … she might even be liable to arrest and incarceration as a prostitute. If she was a widow, she could be denied her lawful dower rights, even custody of her own children. … her "marriage lines" were proof of one of the most important achievements of her life, and might be her best protection against life’s vicissitudes.” (Kane, 2008)

Wedding Breakfast

Since weddings were held in the morning, the meal eaten afterwards was considered breakfast. "The breakfast was such as best breakfasts then were: some variety of bread, hot rolls, buttered toast, tongue or ham and eggs. The addition of chocolate [drinking chocolate] at one end of the table, and wedding cake in the middle, marked the specialty of the day."(Austen -Leigh,1920)Unlike the wedding ceremony, friends and relatives were usually invited to the wedding breakfast. Sometimes, though, the bride and groom set off for the post-nuptial travels immediately from the church door, leaving their loved ones to celebrate on their own.

Wedding Cake

Though wedding cakes were baked for most weddings, they were very different from what we envision today. The cake resembled fruitcake, soaked with liberal amounts of alcohol: wine, brandy or rum. Usually the cakes would be covered in almond icing which was then browned in the oven. If a family wanted to display wealth, the cake would be covered in refined sugar icing and left very white. Pure white, refined sugar was very expensive and a sign of affluence. Elizabeth Raffald, in The Experienced English Housekeeper, published the first recipe for such a cake.With all the alcohol, wedding cakes kept for a long time. Pieces would be sent home with family and friends, delivered to neighbors and even send over distances to those who could not be part of the celebrations.

Honeymoons

After the wedding and possibly the breakfast, a newlywed couple would usually go to the husband’s house. If the couple planned a wedding trip, they usually departed a week or so later.Since the war (and finances for most people) made touring the continent out of the question, couples of the era usually planned trips closer to home. They might visit relations to make introductions (and cut down on travel costs) or visit picturesque landscapes like the Lake District or Peaks or seaside resorts like Brighton.

Often, the bride's sister or closest female friend accompanied the couple. To the modern eye the custom seems weird at best, but since the bride and groom might have spent little time alone with one another prior to the wedding, relying only on one another for conversation and company could be very awkward. Having another person along could ease the transition for everyone.

References:

Allen, Louise. Banns or Licence? Ways To Marry in Georgian England May 7, 2014 https://janeaustenslondon.com/2014/05/07/banns-or-licence-ways-to-marry-in-georgian-england/ http://www.regencyresearcher.com/pages/marriage.html Accessed 7/24/2016Austen -Leigh, Mary Augusta. Personal Aspects Of Jane Austen. London John Murray, Albemarle Street. 1920.

Book of Common Prayer. Imprinted at London: By Robert Barker ..., 1632. Book of Common Prayer

Forsling, Yvonne. Weddings During the Regency https://www.janeausten.co.uk/weddings-during-the-regency-era/ Accessed 7/24/2016

Forsling, Yvonne . Regency Weddings: Fashion Periodicals http://hibiscus-sinensis.com/regency/weddingprints.htm Accessed 7/20/2016

Jones, Hazel. Jane Austen and Marriage. London: Continuum, 2009.

Kane, Kathryn. "Marriage Lines" really are lines! 19 December 2008 https://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2008/12/19/marriage-lines-really-are-lines/

Laudermilk, Sharon H., and Teresa L. Hamlin. The Regency Companion. New York: Garland, 1989.

Raffald, Elizabeth. The Experienced English Housekeeper for the Use and Ease of Ladies, Housekeepers, Cooks, &c. Written Purely from Practice ... Consisting of near Nine Hundred Original Receipts, Most of Which Never Appeared in Print. ... The Tenth Edition. ... By Elizabeth Raffald. London: Printed for R. Baldwin, 1786.

Reeves-Brown, Jessamyn. Regency Wedding Details & History http://www.songsmyth.com/weddings.html. Accessed 7/25/16

Sanborn, Vic. And the Bride Wore… June 17, 2011. https://www.janeausten.co.uk/and-the-bride-wore/. Accessed 7/26/16

Wilson, Carol. Gastronomica: The Journal Of Food And Culture, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 69–72, issn 1529-3262.

Find previous installments of this series here:

Get Me to the Church on Time: Changing Attitudes toward MarriageTo Have a Courtship, One Needs a Suitor

Nothing is ever that simple: Rules of Courtship

Show me the Money: the Business of Courtship

The Price of a Broken Heart

Making an Offer of Marriage

Games of Courtship

The Hows and Why of Eloping

Licenses, Laws and Legalities of Marriage

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Click here to find her books on Amazon. For more on her writing and other Random Bits of Fascination, visit her website. You can also like her on Facebook, follow on Twitter or email