By Chris Thorndycroft

In February of 1748, an elderly customs official named William Galley was escorting a witness called Daniel Chater from Southampton to Chichester to testify against a gang of smugglers who had broken into the customs house at Poole earlier that year. The pair stopped at the White Hart in Rowlands Castle for refreshment before the final leg of their journey. Unfortunately for them, the inn was a regular meeting point for members of the Hawkhurst Gang; the very smugglers whom the witness was to testify against. Once aware of the mission of the two men, the smugglers plied them with drink and spirited them away into the night.

In February of 1748, an elderly customs official named William Galley was escorting a witness called Daniel Chater from Southampton to Chichester to testify against a gang of smugglers who had broken into the customs house at Poole earlier that year. The pair stopped at the White Hart in Rowlands Castle for refreshment before the final leg of their journey. Unfortunately for them, the inn was a regular meeting point for members of the Hawkhurst Gang; the very smugglers whom the witness was to testify against. Once aware of the mission of the two men, the smugglers plied them with drink and spirited them away into the night.

Galley’s body was later found shoved inside an enlarged foxhole at Harting Coombe. His arms were raised upwards as if shielding himself from being buried alive. Chater was found at the bottom of a well in Lady Holt Park, his body crushed by debris that had been pelted down on him. Both men had been cruelly tortured. The hunt for their killers began in earnest and the village of Rowlands Castle became the centre of a criminal investigation that shocked the nation.

This was the village I was born to.

|

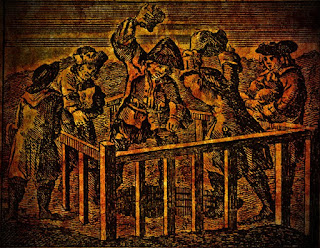

| The smugglers finish off Daniel Chater after throwing him down a well at Lady Holt Park. |

For the first eight years of my life I lived in a little cottage a mile down the road from where the White Hart once stood (it was torn down around 1853 to make room for the railway). Other than an old rumour that the track way past my terrace was once used by smugglers in the 18th century, this colourful chapter in the village’s history was wholly unknown to me until much later.

The gruesome events of February, 1748 were first described to me simply as a violent altercation between smugglers and customs men. Imagining some sort of Wild West gunfight occurring in my local village pub, I did a bit of digging. The truth was not hard to find. As well as the Old Bailey records and an entry in the Newgate Calendar, the whole nasty affair was recorded in a series of illustrated pamphlets entitled The Genuine History of the Inhuman and Unparalleled Murders of Mr. William Galley, a Custom-House Officer, and Mr. Daniel Chater, a Shoemaker.

Written by ‘a gentleman of Chichester’, the pamphlets were published in 1758 and began by outlining the background to these appalling crimes. In September of 1747, a smuggling run organised by the notorious Hawkhurst Gang went awry when their cutter, the Three Brothers and its cargo of two tons of tea and thirty casks of spirits was seized by a revenue ship. The cargo was stored at the customs house at Poole.

Incensed by this, the Hawkhurst Gang held council in Charlton Forest and, on the 6th of October, they raided the customs house and stole back the tea and spirits. Making their way back east, they passed through the village of Fordingbridge where a crowd tuned out to greet them as heroes. One of the smugglers - John ‘Dimer’ Diamond - shared a few words with Daniel Chater (an old acquaintance) and passed him a small bag of tea. This exchange did not go unnoticed.

|

| Frontispiece for the collected pamphlets that sensationalised the case |

Soon Dimer was arrested and put in irons at Chichester jail. The rest of the Hawkhurst Gang were thrown into a panic. If Dimer turned king’s evidence, he could name every last one of them. Fortune favoured the gang and, on the 14th February, customs officer William Galley and his charge Daniel Chater, wandered into the yard of the White Hart.

The smugglers’ decision to remove this threat to them was unanimous although the means were a matter of heated debate. Should they kill them? Kidnap them and hold them until the trial had been held? Ship them to France?

Whatever their decision it was clear that the two strangers had to be made as drunk as possible. Round after round of drinks was bought and, as the two inebriated men were escorted to their beds, a letter was pilfered from the pocket of William Galley. The contents of the letter – a request to the local Justice Battine to examine the witness – emphasised the danger to the smugglers. The most senior of them – William Jackson and his accomplice, William Carter – seized the men in their beds and dragged them out into the yard where they were put on horses, their legs tied underneath.

The unfortunate men were horsewhipped for five miles in the direction of Lady Holt Park where the smugglers intended to dispatch them and toss their bodies down a well. William Galley begged for his life which drove Jackson (a sadistic villain even in these circles) to further savagery.

The gang made a detour for Rake where Daniel Chater was chained up in a turf hut to await further punishment. William Galley, who was now presumed dead after sliding off his horse and having his skull kicked in by its hoof, was taken to Harting Coombe and buried, although not before regaining consciousness it seems.

After showing their faces at their respective employments the following week, the smugglers returned to the turf hut to finish off Chater. Ben Tapner, a smuggler who showed a nasty streak almost the equal of Jackson’s, slashed Chater twice across the face with his knife, severing his nose and nearly blinding him. The wretch was then taken to the well at Lady Holt Park where, after failing to hang him (the rope was too short) the gang threw him into the well and hurled rocks and bits of timber down on him until his screaming stopped.

William Galley’s coat was found on the road, torn and bloody, but of the two unfortunate men, no further trace could be found.

|

| Charles Lennox, the 2nd Duke of Richmond was instrumental in bringing the smugglers to heel. |

Enter Charles Lennox, the second Duke of Richmond. This local aristocrat, whose seat was Goodwood House (now famous for its racetracks), hated smugglers with a passion. He was a staunch anti-Jacobite (he served under the king’s son against the ’45 rebellion) and the support smugglers often lent the Catholic cause only fuelled his wish to see them destroyed. The mysterious disappearance of a customs official and his witness while travelling through the duke’s domain would likely have roused his personal interest.

Somebody clearly counted on this for an anonymous letter was sent to the duke, telling where Galley’s body was buried. A second letter even named one of the smugglers – William Steele – as an accomplice in the murders and he quickly joined his comrade Dimer at Chichester jail. A confession was wrung out of him along with thirteen other names. The manhunt began and in January, 1749, the villains went on trial for the murders of Galley and Chater.

The case was sensational for its time, no doubt helped by the series of illustrated pamphlets written by our anonymous ‘gentleman of Chichester’ (widely believed to have been the Duke of Richmond himself). The sadistic violence of the smugglers shocked the public and dispelled the belief that smuggling was a harmless crime committed by heroic types brave enough to flaunt King George’s harsh tax laws. The trial and media coverage turned the public’s opinion against smuggling and the days of its golden age were numbered.

The Duke of Richmond died the following year and is perhaps better remembered for his patronage of cricket, but his contributions to stamping out smuggling in Hampshire and Sussex cannot be ignored. The trial effectively broke up the Hawkhurst Gang and various other leaders of the group were apprehended, tried and executed shortly after. The life of the duke and his relationship with his four rebellious daughters formed the basis of Stella Tillyard’s book Aristocrats and the 1999 BBC miniseries of the same name.

|

| The Castle Inn at Rowlands Castle stands on the same site the White Hart once did. |

Having learned the details of what I had previously thought of as a quick battle between smugglers and excise men in my local area, I knew that I had to work them into a novel somehow. The Hawkhurst Gang and its practice of murdering witnesses and intimidating judges smacked of an 18th century English mafia that extended from Kent to Dorset and was a thrilling piece of local history I had been wholly unaware of before my investigations.

The White Hart, sadly gone, is remembered in the bricks and mortar of the Castle Inn which was built very nearby purportedly using the same materials. Rowlands Castle now has a railway station, at least three other pubs, countless shops and small businesses and a housing estate. It looks little different from any other village in the south of England but it will always have this dark chapter in its history that recalls casks of brandy deposited on shingle beaches, shadowed types leading packhorses down moonlit country lanes, and murder, torture and violence employed to ensure that people kept their mouths shut.

Chris Thorndycroft’s new novel The Rebel and the Runaway is told from the point of view of Alice Sinclair; a young girl who runs away from home and winds up as a barmaid at the White Hart. In love with one of the smugglers, she becomes embroiled in the dreadful events surrounding the murders of Galley and Chater. On the run, in peril and torn between family and love, Alice’s story is one of passion and defiance, entwined with one of England’s most shocking murder cases.

Chris Thorndycroft’s new novel The Rebel and the Runaway is told from the point of view of Alice Sinclair; a young girl who runs away from home and winds up as a barmaid at the White Hart. In love with one of the smugglers, she becomes embroiled in the dreadful events surrounding the murders of Galley and Chater. On the run, in peril and torn between family and love, Alice’s story is one of passion and defiance, entwined with one of England’s most shocking murder cases.

Chris Thorndycroft is also the author of the Hengest and Horsa Trilogy and the ghost story novella The Visitor at Anningley Hall (a prequel to M. R. James’s ‘The Mezzotint’). He also writes Steampunk and Retropulp under the pseudonym P. J. Thorndyke.

Visit his blog here.