For almost thirty years, I have used the example of Julius Caesar's supposed "invasions" of Britain, in 55 and 54 BC, to impress upon my students just how much might have happened in the remote past, whilst leaving no apparent trace in the archaeological record. We know of these incursions from Caesar's own account of the Gaulish Wars, and, whilst it has long been understood that he was writing propaganda to advance his political career in Rome, it hardly seemed likely that he would have told an absolutely blatant lie, given that he would be returning to Rome with tens of thousands of troops, who would have a clear idea as to where they had or had not been.

|

| Julius Caesar, Musee d'Arles. Photo: Mcleclat (licensed under GNU). |

For all of this, until very recently, I could not point to a single piece of unambiguous archaeological evidence (not a sword, a spearhead, a skeleton, or a ditch) to suggest a Roman military presence on these islands prior to the Emperor Claudius's invasion in 43 AD. I always had in mind that such evidence might come to light at any stage, and now, it seems, it has, thanks to an excavation by University of Leicester archaeologists, at Pegwell Bay, on the Isle of Thanet, Kent.

Caesar's first visit to Britain was very much an exploratory expedition, as he himself explains:

" ... Caesar ... set out for Britain, aware as he was that our enemies in almost all our wars with the Gauls had received reinforcements from that quarter. He considered, moreover, that even if the season left no time for a campaign, none the less it would be a great advantage to him simply to land on the island and observe the kind of people who live there and its localities, harbours, and approaches ... " (from the Oxford World's Classics translation by Carolyn Hammond).

Caesar's two legions (around 12,000 men) encountered more resistance than they might have expected (presumably from warriors of the Cantiaci tribe of Kent), and his ships' captains were also surprised by the ferocity of the autumn gales in the English Channel. A disaster narrowly averted, he returned with his force to Gaul.

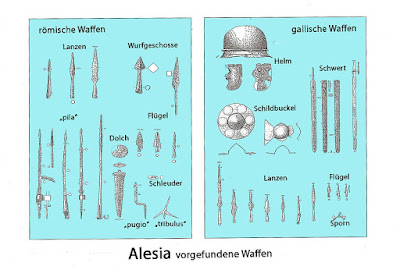

During Caesar's absence, it seems that tribal war broke out in Britain. A man named Mandubracius, a prince of the Trinovantes tribe of Essex, made his way to Gaul, and requested Caesar's support to recover lands that had been seized from his people by the more powerful Catuvellauni tribe of Hertfordshire. Caesar agreed, and returned to Britain with a much larger force. It is the landing site of this army that may have been discovered at Pegwell Bay. The Roman fort, probably a tented camp, may cover an area as large as twelve hectares in size, and has a ditch four to five metres wide, and two metres deep: it is securely dated to the First Century BC, and finds include a Roman spearhead closely comparable to examples found at the French site of Alesia, which Caesar is known to have besieged a few years later.

|

| Map, showing the location of Pegwell Bay, John Richard Green (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| Pegwell Bay, Kent. Photo: Ron Strutt (licensed under CCA). |

|

| Reconstructed fortifications at Alesia. Photo: Carole Raddatto (licensed under CCA). |

|

| Roman (left) and Gaulish (right) weapons found at Alesia. Image: Jochen Jahnke (Public Domain). |

This time, Caesar's legions fought their way through Kent, probably crossing the Medway and the Thames, and finally defeating the Catuvellaunian King, Cassivellaunus, possibly at his stronghold in Hertfordshire. It still was not Caesar's intention, however, to leave a Roman garrison in Britain: he secured a promise from Cassivellaunus to stop molesting the Trinovantes (but Cassivellaunus's successor was minting coins on Trinovantian territory only a few years later); took "hostages" from the Catuvellauni (not nearly as frightening a prospect as it might have appeared - these were aristocratic young men who would be fostered out to the wealthiest families in Rome, given an education worthy of a Consul's son, and, if circumstances allowed returned to Britain to rule as thoroughly pro-Roman client kings).

|

| Bigbury Camp, Kent, the possible site of a battle between Caesar's 7th Legion and the warriors of the Cantiaci tribe. Photo: Google earth (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| The Devil's Dyke, near Saint Alban's, Hertfordshire, the possible site of Caesar's defeat of King Cassivellaunus. Photo: Colin Riegels (image is in the Public Domain). |

For a further century, Rome traded peacefully with the British tribes; sent ambassadors and diplomatic gifts to them; and played one tribe off against on another to their own advantage; until, in 43 AD, renewed conflict between the Catevellauni and their neighbours to the east and south provided the pretext for the Emperor Claudius's invasion, which resulted in most of Britain being absorbed into the Roman Empire.

~~~~~~~~~~

Mark Patton blogs regularly on aspects of history and historical fiction at https://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk. He is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be purchased from Amazon.

Fascinating to hear about this.

ReplyDeleteAs usual, a fascinating post.

ReplyDelete