by Mark Patton

In an earlier blog-post, Grace Elliot explored the remarkable London home (now a museum) of the Georgian architect, Sir John Soane (1753-1837). I have visited the museum many times, sometimes with friends, sometimes with my students, and, each time, have discovered something new, but my intention here is rather to explore his life and the buildings he designed, some of which are still standing, some of which have subsequently been demolished, and some of which were never built at all. At some point in the next few weeks, I will visit the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition, where, among the paintings and the sculptures, I will see designs by some of our greatest living architects. Soane was there before them; he was Professor at the Royal Academy and regularly exhibited his designs at the Summer Exhibition.

Soane's father has sometimes been described as a bricklayer, but it is probably more accurate to think of him as a builder. He was wealthy enough to secure for his son a private education, albeit not at one of England's great public schools. Soane went on to serve his apprenticeship as an architect with George Dance the Younger, and then, at the age of 25, embarked on a Grand Tour, travelling via Versailles to Rome and Naples and returning via Switzerland after three years.

A Grand Tour would not normally have been a possibility for a man of limited means, such as John Soane, but he had a travelling scholarship, courtesy of the Royal Academy. Travelling with another young architect, Robert Furze Brettingham, he seems to have approached the experience with rather more seriousness than many of his wealthier contemporaries, earnestly sketching the ruins of the Forum Romanum, Hadrian's villa at Tivoli, and the recently excavated buildings of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

During his travels, he also proved himself an effective networker, meeting a number of influential men who would later become his clients and patrons and would recommend him to their friends. On his return to England, he struggled, at first, to win commissions, but he landed a particularly important one in 1788 with the Bank of England. His scheme for the bank was executed, but almost nothing of it survives. Inspired, however, by the ruins that he had seen in Italy, he even considered how his own buildings might appear as ruins, many centuries after his death.

One commission led to another; he designed private homes, churches (although he was not, personally, religious), and even, at Dulwich, in South London, one of Europe's very first purpose-designed art-galleries. He designed an extension to the Freemasons' Hall in central London, having been initiated into the craft in 1813 (this was built, but no longer survives), and he drew up plans for a new royal palace (probably on the site of London's Green Park), which was never built. All of his designs show the influence of the Roman and Renaissance buildings that he had seen in Italy in his formative years.

Unlike his aristocratic contemporaries, Soane had not returned from his Grand Tour with a large collection of antiquities, but he made up for this, as a successful architect, by buying up the Greek vases and sculptures brought back by younger tourists, who had (after the fashion of many Grand Tourists), overstretched their budgets.

When his beloved wife, Elizabeth, died, Soane designed a funerary monument at Old Saint Pancras Churchyard, which would, in time, become his own sepulchre, as well as hers. It would also become his most ubiquitous and visible legacy, since it inspired a much later architect, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, in his (1935) design for a telephone kiosk, which was rolled out across the British Isles.

~~~~~~~~~~

Mark Patton is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be purchased from Amazon.

In an earlier blog-post, Grace Elliot explored the remarkable London home (now a museum) of the Georgian architect, Sir John Soane (1753-1837). I have visited the museum many times, sometimes with friends, sometimes with my students, and, each time, have discovered something new, but my intention here is rather to explore his life and the buildings he designed, some of which are still standing, some of which have subsequently been demolished, and some of which were never built at all. At some point in the next few weeks, I will visit the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition, where, among the paintings and the sculptures, I will see designs by some of our greatest living architects. Soane was there before them; he was Professor at the Royal Academy and regularly exhibited his designs at the Summer Exhibition.

|

| Sir John Soane, in the regalia of the Masonic Grand Lodge of England |

Soane's father has sometimes been described as a bricklayer, but it is probably more accurate to think of him as a builder. He was wealthy enough to secure for his son a private education, albeit not at one of England's great public schools. Soane went on to serve his apprenticeship as an architect with George Dance the Younger, and then, at the age of 25, embarked on a Grand Tour, travelling via Versailles to Rome and Naples and returning via Switzerland after three years.

A Grand Tour would not normally have been a possibility for a man of limited means, such as John Soane, but he had a travelling scholarship, courtesy of the Royal Academy. Travelling with another young architect, Robert Furze Brettingham, he seems to have approached the experience with rather more seriousness than many of his wealthier contemporaries, earnestly sketching the ruins of the Forum Romanum, Hadrian's villa at Tivoli, and the recently excavated buildings of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

During his travels, he also proved himself an effective networker, meeting a number of influential men who would later become his clients and patrons and would recommend him to their friends. On his return to England, he struggled, at first, to win commissions, but he landed a particularly important one in 1788 with the Bank of England. His scheme for the bank was executed, but almost nothing of it survives. Inspired, however, by the ruins that he had seen in Italy, he even considered how his own buildings might appear as ruins, many centuries after his death.

|

| Lothbury Court, part of Soane's design for the Bank of England, by Thomas Malton Junior, 1801 |

|

| Soane's ground-plan for the Bank of England |

|

| Soane's Bank of England, imagined as a ruin, by J.M. Gandy, 1830 |

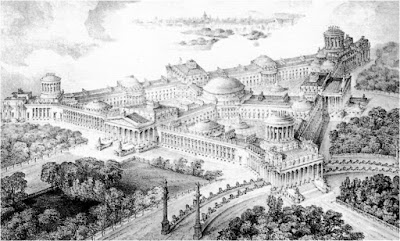

One commission led to another; he designed private homes, churches (although he was not, personally, religious), and even, at Dulwich, in South London, one of Europe's very first purpose-designed art-galleries. He designed an extension to the Freemasons' Hall in central London, having been initiated into the craft in 1813 (this was built, but no longer survives), and he drew up plans for a new royal palace (probably on the site of London's Green Park), which was never built. All of his designs show the influence of the Roman and Renaissance buildings that he had seen in Italy in his formative years.

|

| The Dulwich Picture Gallery. Soane's use of skylights to light the building was inspired by Roman "cryptoportico" structures. Photo: Bridgeman (licensed under GNU). |

|

| Soane's design for a royal palace, 1821 |

Unlike his aristocratic contemporaries, Soane had not returned from his Grand Tour with a large collection of antiquities, but he made up for this, as a successful architect, by buying up the Greek vases and sculptures brought back by younger tourists, who had (after the fashion of many Grand Tourists), overstretched their budgets.

When his beloved wife, Elizabeth, died, Soane designed a funerary monument at Old Saint Pancras Churchyard, which would, in time, become his own sepulchre, as well as hers. It would also become his most ubiquitous and visible legacy, since it inspired a much later architect, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, in his (1935) design for a telephone kiosk, which was rolled out across the British Isles.

|

| The burial vault of the Soane family, at Old Saint Pancras Churchyard. Photo: David Edgar (licensed under CCA). |

|

| Telephone kiosks designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, Covent Garden, London. Photo: Enzo Plazzotta (licensed under GNU). |

~~~~~~~~~~

Mark Patton is a published author of historical fiction and non-fiction, whose books can be purchased from Amazon.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.