by Margaret Porter

Readers of historical novels set in a royal court will be familiar with the terms “lady of the bedchamber” and “maid of honour.” But what were the responsibilities required of these positions, their advantages and disadvantages?

Aristocratic ladies and gentry women of the late 17th century coveted a position at court for many reasons. Proximity to eligible gentlemen—the rich, the powerful, the landed—meant they might marry well, gaining wealth or a title or both. It was a means of promoting family interests, and quite a few courtiers inherited positions held by their parents or grandparents. Often a member of a queen’s retinue became the king’s pampered mistress. By giving birth to a royal bastard, she ensured financial support for her lifetime. Another reason court service was a desirable career for a well-born woman—it ensured an annual salary, room and board, and sometimes even a generous dowry. She wore pretty clothes and received ample attention from male courtiers. She also gained material goods—gifts from the sovereign might include jewellery, lace, clothing, and valuable mementos. On the death of a queen, her clothing and possessions were distributed to those who had served her.

The disadvantages were just as numerous. Salaries and stipends came irregularly and were often in arrears. Providing the monarch with aristocratic companionship was an arduous duty. One had to stand for hours on end, attain perfection in dancing and manners, assist at the royal toilette and robing, determine which visitors were welcome and properly introduce them. Those who had no taste for dalliance fended off libertines intent on seduction. Those who dallied with courtiers ran the risk of an unwanted pregnancy—an ordinary bastard hadn’t the cachet of a royal one. Miss Trevor, said to be the prettiest of the Duchess of York’s maids of honour, abruptly left the court before delivering her bastard child. According to one intimately familiar with Charles II’s household, “the Queen’s and Duchess’s maids of honour…bestow their favours to the right and left, and not the least notice is taken of their conduct.”

Charles II

His was the golden age of the bedchamber lady as royal mistress—or vice versa. Upon his marriage, the King foisted his mistress Barbara Palmer, neé Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine, upon his Portuguese bride, sparking a domestic crisis. Later he chased after the beautiful and elusive Frances Stewart, who returned to the Queen's service after marrying the Duke of Richmond. Even the actress Nell Gwyn, “the indiscreetest and wildest creature that was ever in a court” was given a nominal position in the Queen’s service as a Lady of the Privy Chamber. Her French rival Louise de Kerouaille began as a maid of honour to Charles’s sister, Henriette, Duchess of Orleans, at the French court. Later, as the English king’s mistress, she was assured of a place as a Lady of the Bedchamber, although the Queen would not let her enter it. Her apartments at Whitehall were grander than Her Majesty’s.

James II

A Catholic convert, James’s devotion to his religion never inhibited him from sleeping with ladies of the court. As Duke of York, he preyed upon the ladies who served his first and second wives, such loose-moralled creatures as Diana Kirke, Lady Denham, and many others. Arabella Churchill, who served his first duchess, bore him four children.

Mary II

When Mary and her husband William succeeded her de-throned father, they imposed a new sedateness and propriety upon the court. Her bedchamber ladies and maids of honour were faithful, respectable wives and chaste young maidens. The Countess of Derby, as Groom of the Stole, received £800, with a further £400 as Mistress of the Robes, for a total annual salary of £1200—no mean sum in those days. Her five Ladies of the Bedchamber were paid £500 per year, and usually there were six maids of honour, receiving £200 per year.

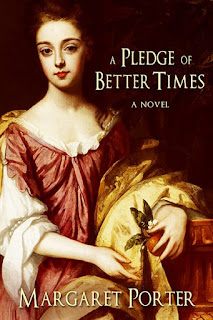

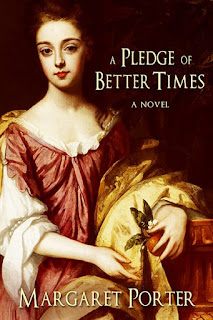

Mary commissioned Godfrey Kneller to paint a series of portraits of the loveliest and most virtuous ladies, known as the Hampton Court Beauties. Among them was the Countess of Dorset, her favourite Lady of the Bedchamber, who died soon after sitting to Kneller. Another attendant, Lady Diana de Vere, whose Hampton Court portrait graces my novel’s cover, bore Mary’s train at her coronation and became the bride of Nell Gwyn’s son Charles, 1st Duke of St Albans. At their marriage, the Queen granted the couple an annuity of £2000.

Queen Anne

Sarah embarked on her long career at court in the 1670s as a maid of honour to Anne Hyde, Duchess of York, and it lasted till her dismissal in the early days of 1711. Her history demonstrates the heights to which a determined female could climb—and also how she could descend, on losing the royal favour.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Margaret Porter is the award-winning and bestselling author of twelve period novels, nonfiction and poetry. Lady Diana de Vere's association with Queen Mary's court is featured in A Pledge of Better Times, her highly acclaimed novel of 17th century courtiers the 1st Duke and Duchess of St. Albans (available in trade paperback and ebook). Margaret studied British history in the UK and the US. As historian, her areas of speciality are social, theatrical, and garden history of the 17th and 18th centuries, royal courts, and portraiture. A former actress, she gave up the stage and screen to devote herself to fiction writing, travel, and her rose gardens.

Margaret Porter is the award-winning and bestselling author of twelve period novels, nonfiction and poetry. Lady Diana de Vere's association with Queen Mary's court is featured in A Pledge of Better Times, her highly acclaimed novel of 17th century courtiers the 1st Duke and Duchess of St. Albans (available in trade paperback and ebook). Margaret studied British history in the UK and the US. As historian, her areas of speciality are social, theatrical, and garden history of the 17th and 18th centuries, royal courts, and portraiture. A former actress, she gave up the stage and screen to devote herself to fiction writing, travel, and her rose gardens.

Readers of historical novels set in a royal court will be familiar with the terms “lady of the bedchamber” and “maid of honour.” But what were the responsibilities required of these positions, their advantages and disadvantages?

Fans of Tudor history and fiction know that several ladies-in-waiting became Queen of England. Anne Boleyn served Queen Katherine of Aragon, as did Jane Seymour—who was also Anne's lady-in-waiting when King Henry began to fancy her. And her successor, Anne of Cleves, had flighty Catherine Howard as a maid of honour.

The Stuarts preferred marrying royalty, but their princes and kings routinely slept with female members of the royal household. Stuart queens had their favourites as well. But royalty were nothing if not fickle, and deep affection could sometimes transform into enmity.

The Stuarts preferred marrying royalty, but their princes and kings routinely slept with female members of the royal household. Stuart queens had their favourites as well. But royalty were nothing if not fickle, and deep affection could sometimes transform into enmity.

|

| A bedchamber lady who rose high & fell far |

The disadvantages were just as numerous. Salaries and stipends came irregularly and were often in arrears. Providing the monarch with aristocratic companionship was an arduous duty. One had to stand for hours on end, attain perfection in dancing and manners, assist at the royal toilette and robing, determine which visitors were welcome and properly introduce them. Those who had no taste for dalliance fended off libertines intent on seduction. Those who dallied with courtiers ran the risk of an unwanted pregnancy—an ordinary bastard hadn’t the cachet of a royal one. Miss Trevor, said to be the prettiest of the Duchess of York’s maids of honour, abruptly left the court before delivering her bastard child. According to one intimately familiar with Charles II’s household, “the Queen’s and Duchess’s maids of honour…bestow their favours to the right and left, and not the least notice is taken of their conduct.”

Ladies-in-waiting and maids of honour served on a rotating basis, one week at a time. They had lodgings in each royal residence. At the top of the hierarchy was the Groom of the Stole, responsible for all the bedchamber staff, and was sometimes also styled First Lady of the Bedchamber. In addition to the ladies and the maids, there were bedchamber women or dressers, of lowlier status, who performed more menial bedchamber tasks.

Charles II

His was the golden age of the bedchamber lady as royal mistress—or vice versa. Upon his marriage, the King foisted his mistress Barbara Palmer, neé Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine, upon his Portuguese bride, sparking a domestic crisis. Later he chased after the beautiful and elusive Frances Stewart, who returned to the Queen's service after marrying the Duke of Richmond. Even the actress Nell Gwyn, “the indiscreetest and wildest creature that was ever in a court” was given a nominal position in the Queen’s service as a Lady of the Privy Chamber. Her French rival Louise de Kerouaille began as a maid of honour to Charles’s sister, Henriette, Duchess of Orleans, at the French court. Later, as the English king’s mistress, she was assured of a place as a Lady of the Bedchamber, although the Queen would not let her enter it. Her apartments at Whitehall were grander than Her Majesty’s.

|

| The "golden" Jane, Mrs Myddelton, in gold |

It was, in a sense, the beginning of the “professional beauty,” whose portrait was painted to hang in royal palaces, and adorned humbler abodes in the form of an engraving. Jane Myddelton, described as “all white and golden,” and “the most beautiful woman in England, and the most amiable,” falls into that category. Frances Jennings, sister of the future Duchess of Marlborough, inspired Anthony Hamilton to write, “Her face reminded me of the dawn, or of some Goddess of the Spring.” On one occasion she and her fellow maid of honour Goditha Price, disguised as orange girls, sold fruit at the theatre. They went unrecognised by the male courtiers who accosted them, or their mistress the Duchess of York.

Diarist Samuel Pepys is a rich source of information on the exploits and amours of ladies of the court, several of whom fired his admiration and his secret passion.James II

A Catholic convert, James’s devotion to his religion never inhibited him from sleeping with ladies of the court. As Duke of York, he preyed upon the ladies who served his first and second wives, such loose-moralled creatures as Diana Kirke, Lady Denham, and many others. Arabella Churchill, who served his first duchess, bore him four children.

|

| The wild and witty Catherine Sedley |

Catherine Sedley, his most famous mistress, resisted all attempts to dislodge her from his court and his bed, much to the consternation of Mary of Modena, his jealous young queen. Despite the fact that Catherine was Protestant and claimed to be far cleverer than he, James would not set her aside, no matter how his wife and priests urged him. Lord Dorset addressed these lines to her: “Dorinda’s sparkling wit, and Eyes/United, cast too fierce a Light.”

Mary II

When Mary and her husband William succeeded her de-throned father, they imposed a new sedateness and propriety upon the court. Her bedchamber ladies and maids of honour were faithful, respectable wives and chaste young maidens. The Countess of Derby, as Groom of the Stole, received £800, with a further £400 as Mistress of the Robes, for a total annual salary of £1200—no mean sum in those days. Her five Ladies of the Bedchamber were paid £500 per year, and usually there were six maids of honour, receiving £200 per year.

|

| Mary, Countess of Dorset |

At the palace, Mary’s ladies joined her in needlework (her favourite occupation), escorted her to chapel prayers, and read aloud to her. In public they accompanied her to the theatre, on walks and promenades, and even to St. James’s Fair, their identities concealed by black vizard masks.

Queen Anne

|

| Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, wearing her gold key of office |

On assuming England’s throne, Anne designated her longtime companion and confidante Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, Groom of the Stole and Keeper of the Privy Purse. It was this all-powerful aristocrat who “prepared a list of ye ladies of ye best quality, ye nearest ye Queen in age and most suited to her temper to be Ladies of the Bedchamber.” In addition to Sarah there were ten—two of them, not surprisingly, were her own daughters. Each received a salary of £1000. The six maids of honour had a stipend of £300 per annum. The Queen was a firm Tory and Sarah strongly Whig, thus the party affiliation of Her Majesty’s attendants was balanced. By the last years of the reign, the number of bedchamber ladies had dropped to eight.

The royal account books reveal that in 1707, the Master of the Great Wardrobe was given £24 10s to purchase “umbrellas for the Maids of Honour.”

Perhaps in no other reign was the relationship of the bedchamber ladies and the monarch so closely scrutinised, or their political powers—real or presumed—so discussed. Sarah, through her firm—some might even say bullying—management of the Queen, soon put herself out of favour. And it was her own cousin Abigail Masham, neé Hill, who supplanted her as Anne’s caretaker and Keeper of the Privy Purse. But because she was a mere “Mrs,” and of a lower class, she couldn’t have Sarah’s position of Groom of the Stole. It was bestowed upon the extremely aristocratic Duchess of Somerset, who had served at court for many a year and whom Anne greatly respected.

Sarah embarked on her long career at court in the 1670s as a maid of honour to Anne Hyde, Duchess of York, and it lasted till her dismissal in the early days of 1711. Her history demonstrates the heights to which a determined female could climb—and also how she could descend, on losing the royal favour.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Margaret Porter is the award-winning and bestselling author of twelve period novels, nonfiction and poetry. Lady Diana de Vere's association with Queen Mary's court is featured in A Pledge of Better Times, her highly acclaimed novel of 17th century courtiers the 1st Duke and Duchess of St. Albans (available in trade paperback and ebook). Margaret studied British history in the UK and the US. As historian, her areas of speciality are social, theatrical, and garden history of the 17th and 18th centuries, royal courts, and portraiture. A former actress, she gave up the stage and screen to devote herself to fiction writing, travel, and her rose gardens.

Margaret Porter is the award-winning and bestselling author of twelve period novels, nonfiction and poetry. Lady Diana de Vere's association with Queen Mary's court is featured in A Pledge of Better Times, her highly acclaimed novel of 17th century courtiers the 1st Duke and Duchess of St. Albans (available in trade paperback and ebook). Margaret studied British history in the UK and the US. As historian, her areas of speciality are social, theatrical, and garden history of the 17th and 18th centuries, royal courts, and portraiture. A former actress, she gave up the stage and screen to devote herself to fiction writing, travel, and her rose gardens.

Sarah was really a difficult woman who was so confident she did not notice she was being replaced with someone less confrontational. It cost her husband a decisive victory that might have changed the course of history. In later life even her own daughters did not speak to her for prolonged periods. And I still find her fascinating.

ReplyDeleteShe certainly tested the duke's patience at times, and indeed, her behaviour adversely affected his later military career. She was very much her own worst enemy, and the same can be said of Queen Anne as well. Sarah is indeed a most fascinating and complex character--and so convinced that her motives were good. Ultimately, she wasn't very wise in her dealings with royalty!

DeleteI really enjoyed this article - it reacquainted me with Sarah, a lady who I got to know during my 'A' level days

ReplyDeleteThanks very much indeed, Annie. So glad you enjoyed the piece!

DeleteDear Margaret Porter,

ReplyDeleteI was wondering which sources you have used for this blogpost! I am doing a research on maids of honour at the Stuart Court and am lacking a few sources for my research essay.

Thank you!

Happy to help, but first I must locate my reference file for this blog post. In the meantime, please send a message via my website--be sure to include your email and any questions. Thanks for your enquiry! You'll find the email link atop this page http://www.margaretporter.com/connect.html

ReplyDelete