By Mark Patton

On a recent visit to York, I found myself looking into the eyes of a (modern) bronze statue of the Roman Emperor, Constantine I, who acceded to the purple at York on the death of his father in 306 AD. He appeared to be gazing straight through me at a stone pillar that he must have known in life since it stood in the military headquarters building in which he probably gave his first imperial speech.

Constantine would go on to make two of the decisions that shaped the world in which we live. The first, made almost certainly under the influence of his mother, Helena, was to end discrimination against the Christian Church and ultimately adopt it as the religion of the Empire. The second was to relocate the capital of the Empire from Rome to Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople. His new empire was to be an eastward-facing, rather than a westward-facing, empire, and for a Christian Emperor, this meant that it would face towards Jerusalem, the centre of the Biblical world.

Helena lost no time in travelling there and soon wrote to her son, declaring that she had discovered not only the tomb of Christ but also the fragments of the True Cross, the socket in which it had stood, and the nails by which Christ had been affixed to it. In doing so, she inaugurated and invented the institutions of pilgrimage and of the veneration of relics, which were to hold such sway over the Medieval imagination in Europe. Constantine ordered the construction of a church on the site, replacing a temple to Venus that had been built by his predecessor, Hadrian.

An early pilgrim was the 7th Century Frankish Bishop, Arculf, who, having visited Jerusalem and Egypt, was, on his return voyage, shipwrecked off the coast of Iona (one may well question the judgement of his ship's captain), and taken in by Saint Adomnan, the head of the island's monastic community, who wrote a treatise "On the Holy Places," based on Arculf's account.

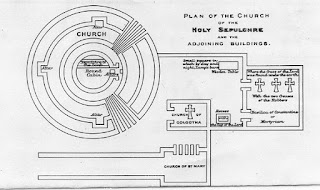

Constantine's Church of the Holy Sepulchre had been badly damaged in 614 AD during a Persian invasion under Khosrau II, so the building seen by Arculf was a reconstruction. It is reasonably clear, however, that there were three elements to the original construction: a circular shrine centred on the tomb of Christ; a rectangular basilica on the site of the crucifixion; and a courtyard separating the two. Early copies of Adomnan's description, including, probably, the one that he himself gave to King Aldfrith of Northumbria, contained illustrations based on a drawing that Arculf himself had drawn on "a tablet covered with wax."

The number of western Europeans in the early middle ages who were able actually to make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem was tiny. Arculf mentioned the presence, in Jerusalem, of many Christian pilgrims, but most are likely to have been Orthodox Greeks and Syriacs or Egyptian Copts, the journey being both too expensive and too dangerous for most Catholics in the west to contemplate.

Descriptions such as Arculf's, therefore, became the basis for a Jerusalem of the mind, a spiritually important, if physically inaccessible, place for most Christians in the west. This Jerusalem of the mind lies at the centre of the imagined world of the Medieval Mappa Mundi, produced not as an aid to navigation, but as a physical expression of a theological world view.

According to this world view, the journey to Jerusalem was one that every Christian must make eventually, but not necessarily in this life, for it was at Jerusalem, and not anywhere else, that Christ would make the Last Judgement between the saved and the damned.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mark Patton blogs regularly on aspects of history and historical fiction at http://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk. His novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications and can be purchased from Amazon.

On a recent visit to York, I found myself looking into the eyes of a (modern) bronze statue of the Roman Emperor, Constantine I, who acceded to the purple at York on the death of his father in 306 AD. He appeared to be gazing straight through me at a stone pillar that he must have known in life since it stood in the military headquarters building in which he probably gave his first imperial speech.

|

| The statue of Constantine in Deansgate, York, commissioned from Philip Jackson RA in 1998. Photo: York Minster (licensed under CCA). |

|

| The Roman column at Deansgate, York, discovered in 1969 beneath a transept of the Minster. Photo: Stanley Howe (licensed under CCA). |

Constantine would go on to make two of the decisions that shaped the world in which we live. The first, made almost certainly under the influence of his mother, Helena, was to end discrimination against the Christian Church and ultimately adopt it as the religion of the Empire. The second was to relocate the capital of the Empire from Rome to Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople. His new empire was to be an eastward-facing, rather than a westward-facing, empire, and for a Christian Emperor, this meant that it would face towards Jerusalem, the centre of the Biblical world.

Helena lost no time in travelling there and soon wrote to her son, declaring that she had discovered not only the tomb of Christ but also the fragments of the True Cross, the socket in which it had stood, and the nails by which Christ had been affixed to it. In doing so, she inaugurated and invented the institutions of pilgrimage and of the veneration of relics, which were to hold such sway over the Medieval imagination in Europe. Constantine ordered the construction of a church on the site, replacing a temple to Venus that had been built by his predecessor, Hadrian.

|

| Saint Helena discovering the True Cross, Italian manuscript of c825 AD, Vercelli, Biblioteca Capitolare, MS CLXV. |

An early pilgrim was the 7th Century Frankish Bishop, Arculf, who, having visited Jerusalem and Egypt, was, on his return voyage, shipwrecked off the coast of Iona (one may well question the judgement of his ship's captain), and taken in by Saint Adomnan, the head of the island's monastic community, who wrote a treatise "On the Holy Places," based on Arculf's account.

Constantine's Church of the Holy Sepulchre had been badly damaged in 614 AD during a Persian invasion under Khosrau II, so the building seen by Arculf was a reconstruction. It is reasonably clear, however, that there were three elements to the original construction: a circular shrine centred on the tomb of Christ; a rectangular basilica on the site of the crucifixion; and a courtyard separating the two. Early copies of Adomnan's description, including, probably, the one that he himself gave to King Aldfrith of Northumbria, contained illustrations based on a drawing that Arculf himself had drawn on "a tablet covered with wax."

|

| The Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, as described by Arculf to Admonan. 9th Century copy, Vienne, Osterreichisches National Bibliothek, Codex 458, f4v |

|

The 7th Century Church of the Holy Sepulchre,

as interpreted by James Rose in 1895,

based on Adomnan's account and the

archaeological evidence.

|

The number of western Europeans in the early middle ages who were able actually to make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem was tiny. Arculf mentioned the presence, in Jerusalem, of many Christian pilgrims, but most are likely to have been Orthodox Greeks and Syriacs or Egyptian Copts, the journey being both too expensive and too dangerous for most Catholics in the west to contemplate.

Descriptions such as Arculf's, therefore, became the basis for a Jerusalem of the mind, a spiritually important, if physically inaccessible, place for most Christians in the west. This Jerusalem of the mind lies at the centre of the imagined world of the Medieval Mappa Mundi, produced not as an aid to navigation, but as a physical expression of a theological world view.

|

| The Cotton map of c1040. Britain and Ireland are at bottom left, emphasising their peripheral status, whilst Sri Lanka ("Taprabanea") is at the top. |

According to this world view, the journey to Jerusalem was one that every Christian must make eventually, but not necessarily in this life, for it was at Jerusalem, and not anywhere else, that Christ would make the Last Judgement between the saved and the damned.

|

| The Last Judgement, from a manuscript of c1050, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius CVI. |

|

| The Valley of Gehenna, Jerusalem, believed to be the gate of Hell. Photo: Deror Avi (licensed under CCA). |

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mark Patton blogs regularly on aspects of history and historical fiction at http://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk. His novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications and can be purchased from Amazon.

I hadn't realised there was more than one Church of the Holy Sepulchre! Thank you! Ah, the Valley of Hinnom! Gat Hinnom, which is where the word Gehenna comes from. I believe its association with hell was because, at one time there were child sacrifices to Moloch there? And these sacrificed involved fire. Shudder! I'm pleased to say that when I was last there, admittedly some time ago, there was a very nice park in the area.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Sue! Yes, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was destroyed several times and rebuilt. What we see today is largely an 11th Century building, set up following a destruction by an earthquake - I'll have more to say about this in a later blog-post. The sacrifices to Moloch, if they ever happened, have, it seems, left few traces in the archaeological evidence.

ReplyDeleteWell, I've been to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, anyway. Very briefly. It was rather dark, as I recall.

ReplyDeleteIf you're dubious about the Moloch thing, it was also, much more prosaically, a rubbish dump, I read. ;-)

Some of my commentary above may be out of date: there's a reassessment of the story of Helena and the discovery of the "True Cross" by Jan Willem Drijvers at www.academia.edu/1040369/Helena_Augusta_the_Cross_and_the_Myth_some_new_reflections. Arculf and his contemporaries, however, would have taken the story as absolute truth.

ReplyDeletethis is really nice post about the holy places in jerusalem.

ReplyDeleteRegards

Shahid

there are many holy places to visit in Greece just like the Sacred Places Greece, tourists can easily explore a lot in Greece as there are many places to visit and many things to do which can keep you busy for days and still you will leave something or the other behind to visit.

ReplyDelete