by Scott Higginbotham

There is a great crashing sound, preceded by a series of thuds, all sharp and bone-jarring. Dust and loose mortar rain down on your exposed head, and you cough, hoping to clear your lungs. Grit fills your eyes, and just when you gain your bearings and stumble to your feet the same sharp pounding repeats.

Walls shift and glass shatters as the only world you know is bathed in a terrible hail of stones. This couldn’t be happening. It shouldn’t be happening. Heavy blocks are loosened and fall onto tables and chests, and doors splinter as though the foundations of the earth are in peril. The battlements are a storm of chaos and dust, but there is an unearthly moan just beyond bowshot.

Like a waking nightmare, giants groan in the morning haze. Their long arms sweep and swivel on an axis, clawing huge stones from the earth to pummel your walls. They never rest, and they never sleep. They are immune to sword and arrow. Armored knights on their proud destriers have small chance at striking fear in the hearts of these wooden beasts.

The trebuchet was a medieval siege engine that could force a breach in a castle wall. Fitted stone, no matter how stout doesn’t stand a chance under a determined assault. If a siege tower or scaling ladder failed to give an army access to the battlements, and there were a host of factors that could affect that – terrain, weather, expendable soldiers – then a projectile-throwing device with a long range could make that a possibility. A handful of engineers, a steady supply of stones, and patience are the main ingredients needed to topple a castle wall.

Other devices were used in siege warfare. The ballista was similar to a giant crossbow and could fire a long, iron-tipped arrow over a long distance. The sharp end could be wound with tow, soaked in pitch, and set ablaze to add to its destructive power. However, it would be ineffective against a stone wall; rather, firing buildings within the walls would do the most damage.

A mangonel is a type of catapult fitted with a bowl-shaped cup on the end of a stout beam. This beam would have been winched tight against rope having a certain amount of elasticity or by physically bending the beam. This type of catapult had its energy stored in either the rope and/or the bend of the wood. As a result, the range was limited along with its lifespan.

By contrast, the trebuchet was different, owing to the fact that its range was longer and its energy was not stored in the curvature of the beam or the relative elasticity of the rope. Rather, the potential is chiefly stored in the counterweight; the heavier the counterweight, the greater the force, velocity, and distance of the projectile.

A simplified description would depict a team of engineers winching the counterweight into the air and locking it into place while the payload would be deposited in the sling. The projectile could range from heavy stones meant to punch through a wall or gatehouse, diseased animal carcasses or excrement for spreading disease or striking fear, or flaming pots of pitch for firing the bailey, thus causing a mass exodus and an opening of the gates.

The basics of this type of catapulting device are summarized as follows [1]

• The machine is powered exclusively by gravity; most often directly by means of a counterweight, though sometimes indirectly (such as in a traction trebuchet).

• Such force rotates a throwing arm, usually four to six times the length of the counterweight arm, to multiply the speed of the arm and, eventually, the projectile.

• The machine utilizes a sling affixed to the end of the throwing arm, acting as a secondary fulcrum, to further multiply the speed of the projectile.

An intimate knowledge of a trebuchet’s inner workings and physics won’t necessarily help defeat a team of them that get wheeled or constructed outside of your walls. In fact, knowing its raw power should cause you to shudder and perhaps sue for terms. Scott Higginbotham writes under the name Scott Howard and is the author of A Soul’s Ransom, a novel set in the fourteenth century where William de Courtenay’s mettle is tested, weighed, and refined, and For a Thousand Generations where Edward Leaver navigates a world where his purpose is defined with an eye to the future. His new release, A Matter of Honor, is a direct sequel to For a Thousand Generations. It is within Edward Leaver's well-worn boots that Scott travels the muddy tracks of medieval England.

There is a great crashing sound, preceded by a series of thuds, all sharp and bone-jarring. Dust and loose mortar rain down on your exposed head, and you cough, hoping to clear your lungs. Grit fills your eyes, and just when you gain your bearings and stumble to your feet the same sharp pounding repeats.

Walls shift and glass shatters as the only world you know is bathed in a terrible hail of stones. This couldn’t be happening. It shouldn’t be happening. Heavy blocks are loosened and fall onto tables and chests, and doors splinter as though the foundations of the earth are in peril. The battlements are a storm of chaos and dust, but there is an unearthly moan just beyond bowshot.

Like a waking nightmare, giants groan in the morning haze. Their long arms sweep and swivel on an axis, clawing huge stones from the earth to pummel your walls. They never rest, and they never sleep. They are immune to sword and arrow. Armored knights on their proud destriers have small chance at striking fear in the hearts of these wooden beasts.

The trebuchet was a medieval siege engine that could force a breach in a castle wall. Fitted stone, no matter how stout doesn’t stand a chance under a determined assault. If a siege tower or scaling ladder failed to give an army access to the battlements, and there were a host of factors that could affect that – terrain, weather, expendable soldiers – then a projectile-throwing device with a long range could make that a possibility. A handful of engineers, a steady supply of stones, and patience are the main ingredients needed to topple a castle wall.

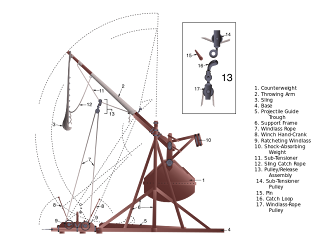

|

| Trebuchet details - Public Domain from Wikimedia Commons |

Other devices were used in siege warfare. The ballista was similar to a giant crossbow and could fire a long, iron-tipped arrow over a long distance. The sharp end could be wound with tow, soaked in pitch, and set ablaze to add to its destructive power. However, it would be ineffective against a stone wall; rather, firing buildings within the walls would do the most damage.

A mangonel is a type of catapult fitted with a bowl-shaped cup on the end of a stout beam. This beam would have been winched tight against rope having a certain amount of elasticity or by physically bending the beam. This type of catapult had its energy stored in either the rope and/or the bend of the wood. As a result, the range was limited along with its lifespan.

By contrast, the trebuchet was different, owing to the fact that its range was longer and its energy was not stored in the curvature of the beam or the relative elasticity of the rope. Rather, the potential is chiefly stored in the counterweight; the heavier the counterweight, the greater the force, velocity, and distance of the projectile.

A simplified description would depict a team of engineers winching the counterweight into the air and locking it into place while the payload would be deposited in the sling. The projectile could range from heavy stones meant to punch through a wall or gatehouse, diseased animal carcasses or excrement for spreading disease or striking fear, or flaming pots of pitch for firing the bailey, thus causing a mass exodus and an opening of the gates.

The basics of this type of catapulting device are summarized as follows [1]

• The machine is powered exclusively by gravity; most often directly by means of a counterweight, though sometimes indirectly (such as in a traction trebuchet).

• Such force rotates a throwing arm, usually four to six times the length of the counterweight arm, to multiply the speed of the arm and, eventually, the projectile.

• The machine utilizes a sling affixed to the end of the throwing arm, acting as a secondary fulcrum, to further multiply the speed of the projectile.

An intimate knowledge of a trebuchet’s inner workings and physics won’t necessarily help defeat a team of them that get wheeled or constructed outside of your walls. In fact, knowing its raw power should cause you to shudder and perhaps sue for terms. Scott Higginbotham writes under the name Scott Howard and is the author of A Soul’s Ransom, a novel set in the fourteenth century where William de Courtenay’s mettle is tested, weighed, and refined, and For a Thousand Generations where Edward Leaver navigates a world where his purpose is defined with an eye to the future. His new release, A Matter of Honor, is a direct sequel to For a Thousand Generations. It is within Edward Leaver's well-worn boots that Scott travels the muddy tracks of medieval England.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.